German A7V tank in Roye, Somme, 26 March 1918.

The ‘March Retreat’ of 1918 is remembered as one of the worst defeats in the history of the British army. After four years of deadlock, in their spring offensive the Germans used innovative new artillery and infantry tactics to break through the trenches of the British Fifth Army and reopen mobile warfare. Fifth Army lost large numbers of men and guns captured, and were forced into headlong retreat. Fuelled by inaccurate newspaper reports, the rumours of disasters on the battlefield were given credibility by the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. In a speech to Parliament on 9 April 1918, Lloyd George cast some aspersions on the performance of Fifth Army, and its commander, General Sir Hubert Gough, who had been sacked on the eighth day of the battle. In Gough’s bitter words, ‘All were … clear that the real cause of the retreat was the inefficiency of myself as a general, and the poor and cowardly spirit of the officers and men.’ But this traditional picture is deeply flawed. Fifth Army was not defeated as badly as some have claimed. Overall, the German spring offensives failed, and their failure represents a British defensive victory.

At the end of 1917 the Germans were presented with a rare window of opportunity to win the First World War. Russia, beaten on the field of battle, had collapsed into revolution, thus releasing large numbers of German troops for use on the Western Front: in the spring of 1918 the Germans could deploy 192 divisions, while the French and British could only muster 156. The German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, introduced at the beginning of the year, had backfired disastrously. Not only had it failed to knock Britain out the war by cutting her vital Atlantic lifeline, it had prompted the United States to enter the war against Germany. As yet, the vast American war machine was still gearing up for action. Substantial numbers of American troops would not reach Europe until the middle of 1918. The German commanders, Hindenburg and Ludendorff, had no desire to sit on the defensive and risk repeating the battering the German army had received at the hands of British at Passchendaele in 1917. They decided to stake everything on one last gamble: to strike in the West and defeat the British Expeditionary Force and French army before the Americans could intervene with decisive numbers. Ironically, the fateful decision was taken at a meeting held at Mons on 11 November 1917. Exactly twelve months later the war ended, in great part as a consequence of the decision taken on that day.

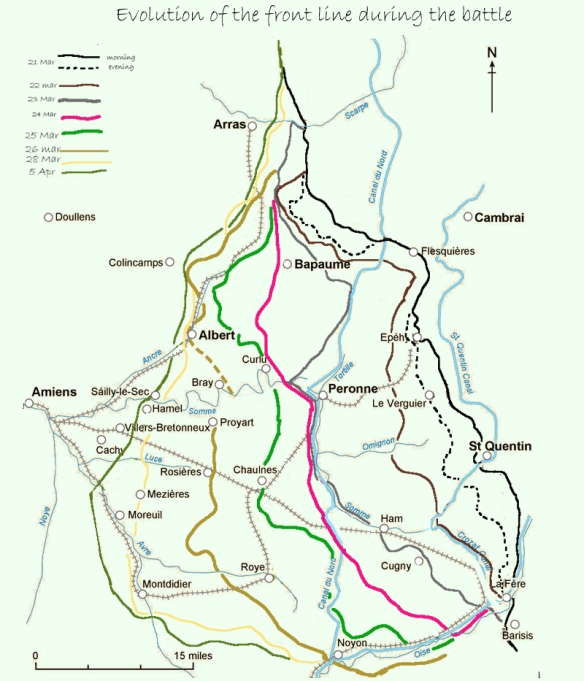

On 21 January the plans were finalised. Operation Michael was an attack on the British, whom the Germans correctly identified as the most dangerous of the Allied forces, in the Somme-Arras sector. Three German armies were to be employed opposite either side of St. Quentin. Opposite Byng’s British Third Army in the Arras area was von Below’s Seventeenth Army, while to their south, covering the Flesquières Salient (created as a result of the Cambrai battles at the end of 1917) and the northern portion of Gough’s British Fifth Army, was von der Marwitz’s Second Army. Both German formations belonged to Crown Prince Rupprecht’s Army Group. Facing Gough’s southern sector was von Hutier’s Eighteenth Army, also of the German Crown Prince’s Army Group. Broadly, the plan was to crack open the British defences, and then push through into open countryside, then wheel to the north and strike the BEF’s flank. Then further attacks could be launched. In the initial stages of the offensive, von Below and von der Marwitz were to capture the old 1916 Somme battlefield before turning north to envelop Arras, while von Hutier was to act as a flank-guard, dealing with any French forces that emerged from the south, and offering support to von der Marwitz’s forces.

The attackers had several advantages over the British. First, numbers. In spite of having greater reserves than the Germans, the British were now suffering from a manpower crisis that had forced divisions to be reduced from twelve infantry battalions to only nine. Haig was forced to make hard choices about where to deploy his divisions. Miscalculating the weight and axis of the German offensive and misled by German deception operations, Haig deliberately left his southernmost Army, Gough’s Fifth, weak. Haig correctly calculated that he could afford to give ground in the Somme area, while to yield territory further north would have been catastrophic. A short advance in the Ypres area, for instance, would have brought the Germans to within striking distance of the coast, which would have imperilled the entire British position. Thus Gough had only 12 divisions to defend 42 miles of front, although he faced 43 German divisions. Byng by contrast had 14 divisions on a 28-mile frontage against 19 German divisions. In the Michael area, the Germans had 2,508 heavy guns against only 976 – a 5 to 2 advantage. Haig gambled on Fifth Army holding out against heavy odds. ‘Never before had the British line been held with so few men and so few guns to the mile; and the reserves were wholly insufficient’.

The second German advantage was in ‘fighting power’. For most of the war, the morale, tactics, and weapons of the two sides were roughly equal. But in March 1918, in terms of tactics, they were not. In the previous two years of almost constant offensives, the BEF had become highly effective at the art of attack. While much play has been made of German ‘stormtroop’ infantry tactics and ‘hurricane’ artillery bombardments used on 21 March 1918, in truth there was little for the BEF to learn from their enemy in this respect. Fighting on the defensive, however, was a novelty, especially because the British had introduced a new concept of defence-in-depth, modelled on the German pattern. In place of linear trenches, defensive positions consisted of Forward, Battle and Rear Zones, utilising machine gun posts, and redoubts. But in many cases, lack of time and labour meant that the Rear Zone was never constructed. Also, the concept was misunderstood at various levels. The Forward Zone was intended to be lightly held, to do little more than delay the attacker and force him to channel his attack where it could be more easily broken up in the Battle Zone by artillery, machine gun fire and local counterattacks. But as many as one third of British infantry were pushed into the Forward Zone. ‘It don’t suit us,’ opined a grizzled veteran NCO. ‘The British Army fights in line and won’t do any good in these bird cages’.

At 4.20 a.m. on 21 March the ‘Devil’s Orchestra’, conducted by Hutier’s innovative head gunner, Colonel Bruchmuller, began the overture to the offensive.

‘It was still dark on the morning of March 21st [1918] when a terrific German bombardment began – “the most terrific roar of guns we have ever heard” … The great push had started and along the whole of our front gas and high-explosive shells from every variety of gun and trench mortars were being hurled over. Everyone [in 54th Brigade] realized that the great ordeal for which they had been training and planning for weeks was upon them.’

Bruchmuller’s gunners hammered the British defenders to the depth of their position. Five hours later, assisted by a dense fog, the infantry assault broke on the battered and disoriented British defenders. By the evening, the situation was critical. The BEF had lost 500 guns and 38,000 casualties, and the Germans had captured the Forward Zone almost everywhere. Worse, in the extreme south Hutier had broken through Gough’s Battle Zone, forcing British III Corps to retreat to the Crozat Canal. Yet even on the first day of the Kaiserschlact, the ‘Imperial battle’, the British had achieved a modest, but nonetheless important success: they had denied the Germans their first day objectives.

German Seventeenth Army’s attack on Byng’s relatively strong and well dug-in Third Army achieved far less than had been intended. Similarly, German Second Army had failed to achieve the breakthrough it had sought. All this was at the cost of 40,000 German casualties. These were caused partly by clumsy tactics and relentless attacking, but also the British seizing the initiative at a local level. These acts of resistance in the early days of Operation Michael ranged from 18th Division’s counterattack at Baboeuf on 24-25 March, to the action of a Lewis Gun team of 24th Royal Fusiliers, led by two NCOs, who went forward to delay the enemy advance on their sector.

22 March saw the renewal of the offensive. British XVIII and XIX Corps fell back, in part as a result of confusion among the British commanders. Third Army was still holding its Battle Zone but was now being outflanked as Fifth Army was pushed back. To the South, von Hutier’s Eighteenth Army had advanced more than twelve miles, and this led Ludendorff to make an important error. He was painfully aware that the offensive was not going according to plan. He complained of the lack of progress of von Below’s army on 22 March, which had a knock-on effect on Second Army. Ever the opportunist, on 23 March – the day that saw the Germans capture the Crozat Canal – Ludendorff decided to make Hutier’s army the point of main effort. Hutier’s Eighteenth Army had originally been given the role of flank-guard, but now, accompanied by Second Army, it was to drive west and southwest to drive a wedge between the BEF and the French. Von Below’s Seventeenth Army and German forces further north were to push back the British. Any Staff College would criticise this plan as breaking two of the fundamental principles of war: to select and maintain the aim and to concentrate force. The resistance of the British defenders had led Ludendorff – whose grasp of strategy and operational art was tenuous at best – to change his plan on the hoof. Now, the Germans were dispersing their force, rather than concentrating it, with disastrous effects.

Nevertheless, the next few days were grim ones for the BEF as the Germans continued to advance. A British soldier wrote on 23 March that ‘we had to make a hasty retreat with all our worldly possessions – every road out of the village was crowded with rushing traffic – lorries, limbers, G.S. wagons, great caterpillar-tractors with immense guns behind them, all were dashing along in an uninterrupted stream …’ He could even look back with affection on normal army rations: ‘I never thought in the days when we looked with disdain on ‘bully’ and biscuits I should ever long for them and cherish a bit of hard, dry biscuit as a hungry tramp cherishes a crust of bread.’ On 27 March Gough was removed from command of Fifth Army. He probably deserved this treatment for the way he handled his offensives of 1916 and 1917; it was Gough’s bad luck to be sacked for a defensive battle that he conducted with some skill.

Even at this stage there were glimmerings of light for the Allies. On 26 March the crisis led to the appointment of the French general Foch as Allied Generalissimo, to coordinate the activities of the Allied forces. This averted the threat of the French concentrating on defending Paris while the British watched for their lines of communications. Moreover Byng’s Third Army decisively defeated the next phase of the German offensive, Operation Mars. On 28 March nine German divisions attacked north of the River Scarpe. The attackers used much the same methods that had proved so successful on 21 March. But this time they were attacking well-constructed positions, without the benefit of fog, and the British forces were numerically stronger and conducted a model defensive battle.

In the light of the completeness of the German failure Ludendorff ordered the assaults against Third Army to halt – he had no taste for an attritional battle. His appreciation was shared by an officer of German 26th Division, who wrote in his diary on 28 March of his hope that if German ‘operations north and south of us succeed the enemy will also have to give way here’: having seen the British defences he feared heavy casualties if ordered to attack. Michael was not, however quite dead, and a few spasms of offensive action remained. Ludendorff now scaled down his objective to that of taking Amiens. But even this was beyond the German troops. They were halted ten miles short of their goal on 4-5 April, at Villers Bretonneux, by Australian and British forces. On the same day Byng was again attacked, and again the Germans were thrown back. By this stage Ludendorff the gambler was prepared to throw in his hand. On 5 April, he called off the Michael offensive and prepared to renew the attack further north.