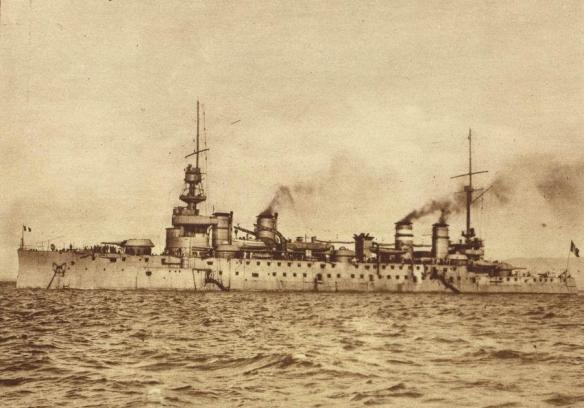

Léon Gambetta underway.

The ‘Gambetta’ class were excellent steamers, able to make over 17 kts on half boilers and to maintain 18 kts for 72 hours continuously. Noted tor their very clear gun decks, the ‘Gambettas’ were better armed than their British contemporaries.

On the night of 27 April 1915, when 15 miles (24 km) south of Santa Maria di Leuca (the south-eastern tip of Italy in the Ionian Sea) in position 39°30′N 18°15′ECoordinates: 39°30′N 18°15′E, she was torpedoed twice by Austro-Hungarian submarine U-5 under the command of Korvettenkapitän Georg Ludwig Ritter von Trapp, patriarch of the Von Trapp Family Singers.

Léon Gambetta was part of the French fleet based at Malta blockading the Austrian Navy in the Adriatic, usually from a position south of the Strait of Otranto. At this time the blockade line was moved further north because of expected Austrian naval activity – the Allies were negotiating with the Italians which shortly led to them declaring war on Austria-Hungary. In spite of the growing threat from Austrian and now German U-boats in the Mediterranean, the armoured cruiser was patrolling unescorted at a reported 7 knots (13 km/h) on a clear, calm night just to the south of the Otranto Straits when she was torpedoed by the U-5.

Léon Gambetta sank in just 10 minutes. Out of 821 men on board, 684 including Rear Admiral Victor Baptistin Senes, commander of the 2nd Light Division, were lost along with all commissioned officers. There were 137 survivors. The French cruiser patrol line was moved South to the longitude of Cephalonia, western Greece. Other sources place her loss 20 miles (32 km) off Cape Leuca.

The return of armored cruisers also seemed like a favorable one to naval officials in many maritime powers owing to the ideas on naval warfare advanced by the U. S. naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan. His book, The Influence of Sea Power on History, was published in 1890. Mahan asserted that, contrary to the French policy of war on commerce as the chief function of a navy, a country must have a strong oceangoing fleet to win control of the sea. This object, known as command of the sea, could be won only in battles where one fleet destroyed the opposing force of another. Once that goal was attained, the power whose fleet controlled the sea-lanes could project its strength around the world. The fleet of that nation could also protect worldwide trade and guarantee its place as a world power. Armored cruisers, despite the fact that Mahan called for a force of battleships at the expense of all smaller ships, still fit into this dogma. They and the largest protected cruisers were increasingly viewed, because of the large growth in size, protection, and armament, as second-class battleships rather than traditional cruisers.

The prime example of the return to the armored cruiser was Great Britain. Faced with the threat of France, Russia, and to an ever-growing extent Germany, the British completed a tremendous number of cruisers. The vast majority were large armored cruisers; the construction of second-class protected ships was discontinued. The Cressy-class comprised six ships completed between 1901 and 1904. These ships were a response to the French Dupuy de Lome and were designed to act as fleet reconnaissance and as a fast battle wing if necessary. This latter role was partially the product of the impression made by cruisers in the line of battle during the Sino-Japanese and Spanish-American wars.

The advantage of steel armor was obvious in these ships. Instead of a narrow armored belt, the new steel extended from the main deck to a depth of 5 feet below the waterline and covered the center of the hull, where the ammunition, barbettes, and engines were housed. This belt had a maximum thickness of 6 inches. Complementing this armor was a limited protective deck. They also had steel bulkheads, essentially walls that separated the compartments of the ship, which added strength to the hull. Finally, the vessel had armor of the same maximum thickness as the belt on its turrets and the barbettes underneath them, while the conning tower had 12 inches of armor. In all respects, this ship was an armored cruiser in the literal sense of the term rather than past ships with limited belt and deck protection.

France followed much the same course as Great Britain in the years leading to 1905. Although the French built seven protected cruisers, the emphasis turned to armored cruisers. France had already been the forerunner with steel armor when its naval constructors built Dupuy de Lome, but attention was paid to reviving this type because of the British building program. It was also partially the result of a continued emphasis on the commerce-raiding ideas of the Jeune École, although the power of the school had declined as each minister of marine that succeeded Admiral Théophile Aube pursued their own policy on the best course to strengthen the navy. Indeed, the chaos that ensued from this situation led in many instances to cruisers built solely for the reason that others were doing the same. From 1899 to 1905, France commissioned 15 armored cruisers. In general terms, these vessels had good speed and sufficient protection, but they suffered greatly as a result of light armament. Some of the last of France’s armored cruisers, the Leon Gambetta-class, were large ships that displaced 12,351 tons on a hull that measured 480 feet, 6 inches by 70 feet, 3 inches, but they mounted only four 7.6-inch guns as primary armament. This deficiency was offset a bit by a secondary armament of 16 6.4-inch quick-firing guns. These weapons, however, were shorter-range ones and could not all train on a target at once, as they were mounted on the sides of the ship. In a long-range battle, cruisers such as these would be severely hampered if they faced enemy armored cruisers, whose weaponry was generally larger.

These cruisers formed the bulk of the modern French Navy because by 1906 the battleships that existed were obsolete as a result of stagnation in their construction. Indeed, the French Navy as early as 1898 was no longer a threat to British naval power. This problem resulted from the disastrous effects of the Jeune École, which created a state of flux in French grand naval strategy, and consequently the building programs, as debates continued to break out between proponents of that school and traditionalists. Lack of clear naval policy hampered the standardization of design, so the fleet comprised a collection of test ships by the turn of the century. France was still a powerful force, but it was no longer number two in the world. By 1905, French weakness and the fear of Germany had led to the Entente Cordiale, a loose defensive understanding with Britain, the year before. Part of this agreement was rough naval plans for use in case of a common war with Germany.