On 15 August 1936, however, the Air Ministry had placed an order for 180 Wellington Mk Is to Specification B. 29/36. These were required to have a redesigned and slightly more angular fuselage, a revised tail unit, and hydraulically operated Vickers nose, ventral and tail turrets. The first production Wellington Mk I was flown on 23 December 1937, powered by Pegasus X engines. In April 1938, however, the 1,050-hp (783-kW) Pegasus XVIII became standard for the other 3,052 Mk Is of all variants built at Weybridge, or at the Blackpool and Chester factories which were established to keep pace with orders.

Initial Mk Is totalled 181, of which three were built at Chester. These were followed by 187 Mk lAs with Nash and Thompson turrets and strengthened landing gear with larger main wheels. Except for 17 Chester-built aircraft, all were manufactured at Weybridge. The most numerous of the Mk I variants was the Mk IC, which had Vickers ‘K’ or Browning machine-guns in beam positions (these replacing the ventral turret I, improved hydraulics, and a strengthened bomb bay beam to allow a 4,000-lb (1814-kg) bomb to be carried. Of this version 2,685 were built (1,052 at Weybridge, 50 at Blackpool and 1,583 at Chester), 138 of them being delivered as torpedo-bombers after successful trials at the Torpedo Development Unit, Gosport.

Many of the improvements incorporated in the Mks IA and IC were developed for the Mk II, powered by 1,145-hp (854-kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin X engines as an insurance against Pegasus supply problems. The prototype was a conversion of the 38th Mk I, and this made its first flight on 3 March 1939 at Brooklands. Although range was reduced slightly, the Wellington II offered improvements in speed, service ceiling and maximum weight, the last rising from the 24,850 lb (11272 kg) of the basic Mk I to 33,000 lb (14969 kg). Weybridge built 401 of this version.

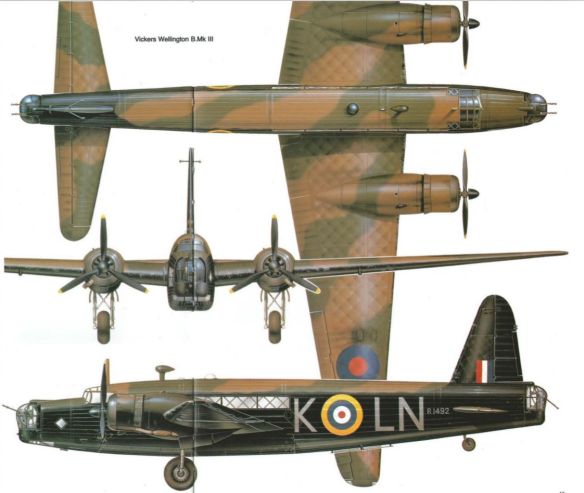

With the Wellington III a switch was made to Bristol Hercules engines, the prototype being the 39th Mk I airframe with Hercules HEISMs, two stage superchargers and de Havilland propellers. After initial problems with this installation, a Mk IC was converted to take two 1,425-hp (1063-kW) Hercules III engines driving Rotol propellers. Production Mk IIIs had 1,590-hp (1186-kW) Hercules XIs, and later aircraft were fitted with four-gun FN.20A tail turrets, doubling the fire power of the installation in earlier marks. Two were completed at Weybridge, 780 at Blackpool and 737 at Chester.

The availability of a number of 1,050-hp (783-kW) Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp R-1830-S3C4-G engines, ordered by but not delivered to France, led to development of the Wellington IV. The prototype was one of 220 Mk IVs built at Chester, but on its delivery flight to Weybridge carburettor icing caused both engines to fail on the approach to Brooklands, and the aircraft made a forced landing at Addlestone. The original Hamilton Standard propellers proved very noisy and were replaced by Curtiss propellers.

For high-altitude bombing Vickers was asked to investigate the provision of a pressure cabin in the Wellington: the resulting Mk V was powered by two turbocharged Hercules VIII engines. Service ceiling was increased from the 23,500 ft (7165 m) of the Mk II to 36,800 ft (11215 m). The cylindrical pressure chamber had a porthole in the lower nose position for the bomb-aimer, and the pilot’s head projected into a small pressurised dome which, although offset to port, provided little forward or downward view for landing. Two prototypes were built in Vickers’ experimental shop at Foxwarren, Cobham, to Specification B. 23/39 and one production machine, to B. 17/40, was produced at the company’s extension factory at Smith’s Lawn, Windsor Great Park.

The Wellington VI was a parallel development, with 1,600-hp (1193-kW) Merlin 60 engines and a service ceiling of 38,500 ft (11735 m), although the prototype had achieved 40,000 ft (12190 m). Wellington VI production totalled 63, including 18 re-engined Mk Vs, all assembled at Smith’s Lawn. Each had a remotely controlled FN.20A tail turret, and this was locked in position when the aircraft was at altitude.

Intended originally as an improved Mk II with Merlin XX engines, the Wellington VII was built only as a prototype, and was transferred to Rolls-Royce at Hucknall for development flying of the Merlin 60s.

First Wellington variant to be developed specifically for Coastal Command was the GR. VIII, a general reconnaissance/torpedo-bomber version of the Pegasus XVIII-engined Mk IC. Equipped with ASV (Air to Surface Vessel) Mk II radar, it was identified readily by the four dorsal antennae and the four pairs of transmitting aerials on each side of the fuselage. A total of 271 torpedo-bombers for daylight operation was built at Weybridge, together with 65 day bombers, and 58 equipped for night operation with a Leigh searchlight in the ventral turret position. In these last aircraft the nose armament was deleted and the position occupied by the light operator.

The designation Mk IX was allocated to a single troop-carrying conversion of a Wellington lA, but the Mk X was the last of the bomber variants and the most numerous. It was based on the Mk III, but had the more powerful 1,675-hp (1249-kW) Hercules VI or XVI engine with downdraught carburettor, and was identified externally from earlier marks by the long carburettor intake on top of the engine cowling. Internal structural strengthening, achieved by the use of newly-developed light alloys, allowed maximum take-off weight to raise to 36,000 lb (16 329 kg). Production was shared between Blackpool and Chester, with totals of 1,369 and 2,434 respectively. After withdrawal from first-line service with Bomber Command, Mk Xs were among many Wellingtons flown by Operational Training Units. After the war a number were converted by Boulton Paul Aircraft as T.10 crew trainers, with the nose turret faired over.

Making use of the experience gained with the Wellington VIII torpedo-bombers, the GR. XI was developed from the Mk X, using the same Hercules VI or XVI engines. It was equipped initially with ASV Mk II radar, although this was superseded later by centrimetric ASV Mk III. This latter equipment had first been fitted to the GR. XII, which was a Leigh Light-equipped anti-submarine version. Weybridge built 105 Mk XIs and 50 Mk XIIs, while Blackpool and Chester respectively assembled 75 Mk XIs and eight Mk XIIs, but with 1,735-hp (1294-kWl Hercules XVII engines Weybridge was responsible for 42 Mk XIIIs and 53 Mk XIVs, Blackpool for 802 XIIIs and 250 Mk XIVs, and Chester for 538 Mk XIVs.

A transport conversion of the Mk I, the C.I.A, was further developed as the C.XV, while the C.XVI was a similar development of the Mk IC. They were unarmed, as were the last three basic versions which were all trainers. The T. XVII was a Mk XI converted by the RAF for night fighter crew training with SCR-720 AI (Airborne Interception) radar in a nose radome. Eighty externally similar aircraft, with accommodation for instructor and four pupils and based on the Mk XIII, were built at Blackpool as T. XVIIIs. Finally, RAF-converted Mk Xs for basic crew training were designated T. XIXs. In total 11,461 Wellingtons were built, including the prototype, and the last was a Blackpool-built Mk X handed over on 25 October 1945.

The fourth production Wellington Mk I was the first to reach an operational squadron, arriving at Mildenhall in October 1938 for No. 99 Squadron. Six squadrons, of No. 3 Group (Nos. 9, .37, .38, 99, 115 and 149) were equipped by the outbreak of war, and among units working up was the New Zealand Flight at Marham, Norfolk, where training was in progress in preparation for delivery to New Zealand of 30 Wellington Is. The flight later became No. 75 (NZ) Squadron, the first Dominion squadron to be formed in World War II. Sergeant James Ward of No. 75 later became the only recipient of the Victoria Cross while serving on Wellingtons, the decoration being awarded for crawling out on to the wing in flight to extinguish a fire, during a sortie made on 7 July 1941.

On 4 September 1939, the second day of the war, Wellingtons of Nos. 9 and 149 Squadrons bombed German shipping at Brunsbüttel, sharing with the Bristol Blenheims of Nos. 107 and 110 Squadrons the honour of Bomber Command’s first bombing raids on German territory. Wellingtons in tight formation were reckoned to have such outstanding defensive firepower as to be almost impregnable, but after maulings at the hands of pilots of the Luftwaffe’s JG 1, during raids on the Schillig Roads on 14 and 18 December, some lessons were learned. Self-sealing tanks were essential, and the Wellington’s vulnerability to beam attacks from above led to introduction of beam gun positions. Most significantly, operations switched to nights.

Wellingtons of Nos. 99 and 149 Squadrons were among aircraft despatched in Bomber Command’s first attack on Berlin, which took place on 25/26 August 1940; and on 1 April 1941, a Wellington of No. 149 Squadron dropped the first 4,000-lb (1814-kg) ‘blockbuster’ bomb during a raid on Emden. Of 1,046 aircraft which took part in the Cologne raid during the night of 30 May 1942, 599 w ere Wellingtons. The last operational sortie by Bomber Command Wellingtons was flown on 8/9 October 1943.

There was, however, still an important role for the Wellington to play with Coastal Command. Maritime operations had started with the four DWI Wellingtons: these had been converted by Vickers in the opening months of 1940 to carry a 52-ft (15.85-m) diameter metal ring, which contained a coil that could create a field current to detonate magnetic mines. Eleven almost identical aircraft, with 48-ft (14.63-m) rings, were converted by W. A. Rollason Ltd at Croydon, and others on site in the Middle East.

No. 172 Squadron at Chivenor, covering the Western Approaches, was the first to use the Leigh Light-equipped Wellington VIII operationally, and the first attack on a U-boat by such an aircraft at night took place on 3 June 1942, with the first sinking recorded on 6 July. From December 1941 Wellingtons were flying shipping strikes in the Mediterranean, and in the Far East No. 36 Squadron began anti-submarine operations in October 1942.

In 1940 the entry of the Italians into World War II resulted in Wellingtons being sent out from Great Britain to serve with No. 205 Group, Desert Air Force. No. 70 Squadron flew its first night attack on 19 September, against the port of Benghazi, and as the tide of war turned during 1942 and 1943, units moved into Tunisia to support the invasions of Sicily and Italy, operating from Italian soil at the close of 1943. The last Wellington bombing raid of the war in southern Europe took place on 13 March 1945, when six aircraft joined a Consolidated Liberator strike on marshalling yards at Treviso in northern Italy.

In the Far East, too, Wellingtons served as bombers with No. 225 Group in India, Mk ICs of No. 215 Squadron flying their first operational sortie on 23 April 1942. Equipped later with Wellington Xs, Nos. 99 and 215 Squadrons continued to bomb Japanese bases and communications until replaced by Liberators in late 1944, when the Wellington units were released for transport duties.

After the war the Wellington was used principally for navigator and pilot training, Air Navigation Schools and Advanced Flying Schools until 1953.