A key objective of the High Seas Fleet commander, Gustav von Ingenohl (1857-1933) was to reduce the strength of the Grand Fleet to such a degree that a subsequent fleet action would have the prospect of German success. Before the war, it had been anticipated that a close blockade strategy would be pursued by the Grand Fleet, leaving it open to decimation by mine and torpedo. However, in the event the British, recognising the impracticability of the time-hallowed close blockade, adopted the alternate strategy of distant blockade – effectively stopping the exits of the North Sea to prevent commerce passing through. Accordingly, other approaches were required to carry through a reduction in Grand Fleet strength. Apart from wider-ranging minelaying and submarine activity, it was decided to carry out surface operations of sufficient size to draw out a part – but not all – of the British battlefleet, which would then be surprised and obliterated by the lurking High Seas Fleet. The ‘bait’ for such operations would be the large cruisers of the I. SG.

The Yarmouth Raid

The first such operation began on 2 November 1914, when the I. SG, comprising Seydlitz (flag), Von der Tann, Moltke and Blücher, supported by the II. SG’s small cruisers Straßburg, Graudenz, Kolberg and Stralsund, sailed to bombard the coastal town of Yarmouth, and lay mines between there and Lowestoft. Two squadrons of battleships and supporting vessels sailed some time later to provide the ‘ambush’ force.

In the event, the next morning the raiding force did no more than land a few shells on the beach (which were armour-piercing, high-explosive ones not then being available) and skirmish with British light forces, a force of British battlecruisers being ordered towards the action long after the raiders had begun to withdraw. The only direct losses were HMS/M D5, sunk by a mine laid by Stralsund, and three British trawlers. However, Yorck, serving with the covering force, strayed into a German defensive minefield at the mouth of the Jade on the morning of 4 November, having missed the swept channel in fog while attempting to reach Wilhelmshaven ahead of the rest of the fleet to rectify defects; she sank with the loss of 336 men.

The Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby Raid

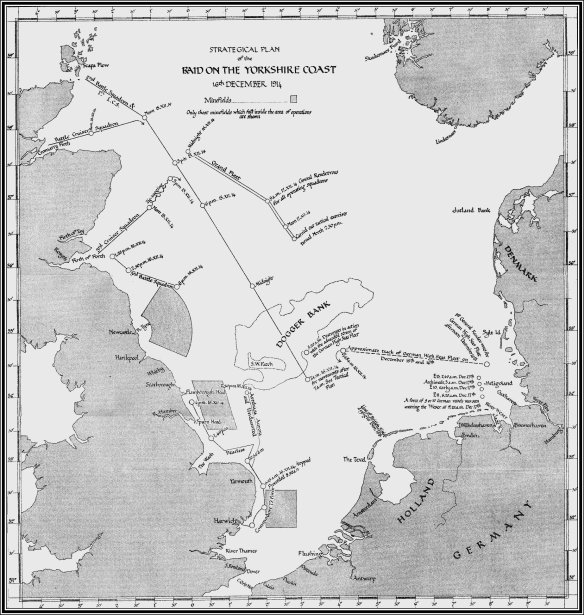

A further operation of the this type was to be carried out by the same group of cruisers, augmented by the brand-new Derfflinger, together with eighteen torpedo boats, against three further coastal towns on 16 December. All three squadrons of battleships of the High Seas Fleet were deployed in support 130nm to the east (the III. Sqn being only five strong, as the brand-new König was under repair and Markgraf and Kronprinz had still to complete their trials), together with the two surviving ships of the III. SG, the seven ships of the IV. SG and fifty-four torpedo boats. Submarines were placed off Harwich and the Humber to attack any British ships reacting from these ports.

The departure of the cruisers on 15 December was detected by British code-breakers3 – but not that of the battlefleet. Thus, the response was to dispatch just the BCS (Lion, Queen Mary, Tiger and New Zealand – the remaining four British battlecruisers were overseas), the 2nd BS (King George V, Ajax, Centurion, Orion, Monarch and Conqueror), the 1st LCS (Southampton, Birmingham, Falmouth and Nottingham) and destroyers from the Grand Fleet, plus the light cruisers Aurora and Undaunted and forty-two destroyers from Harwich and the armoured cruisers of the 3rd Cruiser Sqn (Devonshire, Antrim, Argyll and Roxburgh) from Rosyth. This assemblage was placed to intercept the German raiding force on its return voyage.

Bad weather meant that all the small cruisers except Kolberg (carrying mines) and torpedo boats were detached from the raiding force to return home early on the morning of the 16th. Seydlitz, Blücher and Moltke were to bombard Hartlepool, while Derfflinger, Von der Tann and Kolberg were to attack Scarborough and Whitby. Hartlepool was defended by 6in [152mm]-armed shore batteries, a pair of light cruisers and destroyers, the batteries scoring four hits on Blücher, one on the forward superstructure disabling two 8.8cm guns and killing nine. The second hit was on a starboard 21cm turret, wrecking its sight and rangefinder, but leaving it still operational, the third shell striking the belt below. The fourth hit the foremast, damaging aerials and other equipment. Seydlitz received three hits, one on the forecastle, one which passed through the casing of the fore funnel, making a 4 to 5 metre-square hole in the uptake itself, and one on the aft superstructure, splinters from which penetrated the low-pressure turbine room; however, there were no casualties. Moltke received a single hit, forward.

Of the four British destroyers patrolling in the area, Doon, Test, Waveney and Moy, only the first-named was able to attack the German force, firing three torpedoes, all of which missed, the destroyer retiring damaged. Neither British cruiser was able to come into action, Patrol ran aground after two hits from Blücher, while Forward was only able to leave harbour when the Germans had already begun their retirement.

The bombardment of Hartlepool, during which some 1150 German shells were expended, killing seven soldiers and eighty-six civilians, with fourteen soldiers and 424 civilians injured. Three hundred houses were damaged and significant damage caused to industrial and other infrastructure. At Scarborough, no effective defences were available, significant damage being caused by the cruisers’ secondary and tertiary batteries, 333 15cm and 443 8.8cm shells being expended. Von der Tann and Derfflinger then sailed for Whitby to destroy the signal station there, firing 106 15cm and 82 8.8cm shells. Their tasks finished, the ships then sailed for their rendezvous point, beginning the homeward journey around 11.00.

Meanwhile, at 05.15, the screens of the British force and the High Seas Fleet had come into contact. Roon which, with Prinz Heinrich, was in the van of the High Seas Fleet, ran into Lynx and Unity, but no shots were exchanged. Unfortunately for the Germans, concerns at exceeding standing orders regarding avoiding action with potentially superior forces meant that it was decided at this point to withdraw the High Seas Fleet – only a few minutes away from encountering just the kind of detached element of the Grand Fleet that the strategy had envisaged as the fleet’s victim. The likely outcome of an engagement between the British squadrons and the much larger High Seas Fleet has been much debated. The British had superior speed (in particular given the speed-handicap of the II. Sqn) and could have fairly easily withdrawn, but it is possible that they could have decided to stand and fight: given the issues regarding British shells and damage-resistance that became apparent at Jutland, a negative outcome for the British would have not been unlikely.

The reversal of the fleet’s course placed Roon at the tail of the line, and at 05.59, the large cruiser, now joined by the small cruisers Stuttgart and Hamburg, again encountered British destroyers, which shadowed her until 06.40, at which point the two small cruisers were detached to deal with them. However, they were recalled at 07.02, and the ships continued home in the wake of the fleet. News of the encounter reached the BCS at 07.55, and New Zealand was directed towards the location of the action, followed by the remainder of the squadron. The pursuit was, however, broken off when news of the Scarborough bombardment diverted the British to attempt to deal with the I. SG.

The remainder of the Grand Fleet then sailed to join the hunt, and during the middle of the day there were a number of encounters between the British and German forces, but various breakdowns in communication within the British forces meant that no action was joined, and the I. SG reached port safely. During the High Seas Fleet’s retreat, HMS/M E11 fired a torpedo at Posen, which missed and all of the fleet returned safety.