The Campaigns of Shalmanesar III.

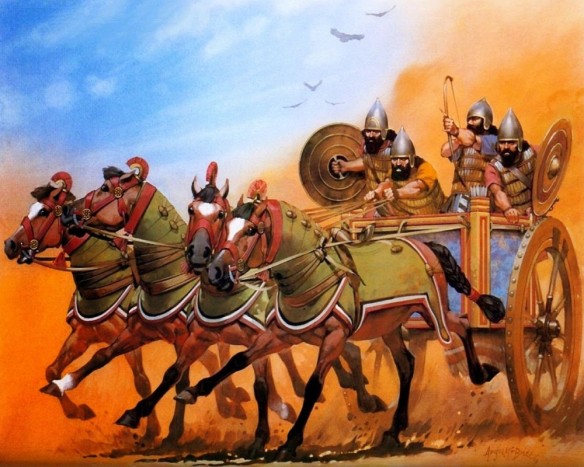

Constantly on the battlefield, starting his campaigns from Nineveh or from one of his provincial palaces, Ashurnasirpal’s son, Shalmaneser III (858 – 824 B.C.), appears to have spent only the last years of his life in Kalhu. Yet it is from that city and its neighbourhood that come his most famous monuments. One of them is the ‘Black Obelisk’ found by Layard in the temple of Ninurta over a century ago and now in the British Museum. It is a two-metre-high block of black alabaster ending in steps, like a miniature ziqqurat. A long inscription giving the summary of the king’s wars runs around the monolith, while five sculptured panels on each side depict the payment of tribute by various foreign countries, including Israel, whose king Jehu is shown prostrate at the feet of the Assyrian monarch. More recent excavations at Nimrud have brought to light a statue of the king in the attitude of prayer, and a huge building situated in a corner of the town wall, which was founded by him and used by his successors down to the fall of the empire. This building, nicknamed by the archaeologists ‘Fort Shalmaneser’, was in fact his palace as well as the ekal masharti of the inscriptions, the ‘great store-house’ erected ‘for the ordinance of the camp, the maintenance of stallions, chariots, weapons, equipment of war, and the spoil of the foe of every kind’. In three vast courtyards the troops were assembled, equipped and inspected before the annual campaigns, while the surrounding rooms served as armouries, stores, stables and lodgings for the officers. Finally, we have the remarkable objects known as ‘the bronze gates of Balawat’. They were discovered in 1878 by Layard’s assistant Rassam, not at Nimrud, but at Balawat (ancient Imgur-Enlil), a small tell a few kilometres to the north-east of the great city. There Ashurnasirpal had built a country palace later occupied by Shalmaneser, and the main gates of this palace were covered with long strips of bronze, about twenty-five centimetres wide, worked in ‘repoussé’ technique, representing some of Shalmaneser’s armed expeditions; a brief legend accompanies the pictures. Besides their considerable artistic or architectural interest, all these monuments are priceless for the information they provide concerning Assyrian warfare during the ninth century B.C.

In the number and scope of his military campaigns Shalmaneser surpasses his father. Out of his thirty-five years of reign thirty-one were devoted to war. The Assyrian soldiers were taken farther abroad than ever before: they set foot in Armenia, in Cilicia, in Palestine, in the heart of the Taurus and of the Zagros, on the shores of the Gulf. They ravaged new lands, besieged new cities, measured themselves against new enemies. But because these enemies were much stronger than the Aramaeans of Jazirah or the small tribes of Iraqi Kurdistan, the victories of Shalmaneser were mitigated with failures, and the whole reign gives the impression of a task left unfinished, of a gigantic effort for a very small result. In the north, for instance, Shalmaneser went beyond ‘the sea of Nairi’ (Lake Van) and entered the territory of Urartu, a kingdom which had recently been formed amidst the high mountains of Armenia. The Assyrian claims, as always, complete success and describes the sack of several towns belonging to the King of Urartu, Arame. Yet he confesses that Arame escaped, and we know that during the next century Urartu grew to be Assyria’s main rival. Similarly, a series of campaigns in the east, towards the end of the reign, brought Shalmaneser or his commander-in-chief, the turtanu Daiân-Ashur, in contact with the Medes and Persians, who then dwelt around Lake Urmiah. There again the clash was brief and the ‘victory’ without lasting results: Medes and Persians were in fact left free to consolidate their position in Iran.

The repeated efforts made by Shalmaneser to conquer Syria met with the same failure. The Neo-Hittite and Aramaean princes whom Ashurnasirpal had caught by surprise had had time to strengthen themselves, and the main effect of the renewed Assyrian attacks was to unite them against Assyria. Three campaigns were necessary to wipe out the state of Bit-Adini and to establish a bridgehead on the Euphrates. In 856 B.C. Til-Barsip (modern Tell Ahmar), the capital-city of Bit-Adini, was taken, populated with Assyrians and renamed Kâr-Shulmanashared, ‘the Quay of Shalmaneser’. On top of the mound overlooking the Euphrates a palace was built, which served as a base for operations on the western front. But whether the Assyrians marched towards Cilicia through the Amanus or towards Damascus via Aleppo, they invariably found themselves face to face with coalitions of local rulers. Thus when Shalmaneser in 853 B.C entered the plains of central Syria, his opponents, Irhuleni of Hama and Adad-idri of Damascus (Ben-Hadad II of the Bible), met him with contingents supplied by ‘twelve kings of the sea-coast’. To the invaders they could oppose 62,900 infantry-men, 1,900 horsemen, 3,900 chariots and 1,000 camels sent by ‘Gindibu, from Arabia’. The battle took place at Karkara (Qarqar) on the Orontes, not far from Hama. Says Shalmaneser:

‘I slew 14,000 of their warriors with the sword. Like Adad, I rained destruction upon them…. The plain was too small to let their bodies fall, the wide countryside was used up in burying them. With their corpses, I spanned the Orontes as with a bridge.’

Yet neither Hama nor Damascus were taken, and the campaign ended prosaically with a little cruise on the Mediterranean. Four, five and eight years later other expeditions were directed against Hama with the same partial success. Numerous towns and villages were captured, looted and burned down, but not the main cities. In 841 B.C. Damascus was again attacked. The occasion was propitious, Adad-idri having been murdered and replaced by Hazael, ‘the son of a nobody’. Hazael was defeated in battle on mount Sanir (Hermon), but locked himself in his capital-city. All that Shalmaneser could do was to ravage the orchards and gardens which surrounded Damascus as they surround it today and to plunder the rich plain of Hauran. He then took the road to the coast, and on Mount Carmel received the tribute of Tyre, Sidon and Iaua mâr Humri (Jehu, son of Omri), King of Israel, the first biblical figure to appear in cuneiform inscriptions. After a last attempt to conquer Damascus in 838 B.C. the Assyrian confessed his failure by leaving Syria alone for the rest of his reign.

In Babylonia Shalmaneser was luckier, though here again he failed to exploit his success and missed the chance which was offered to him. Too weak to attack the Assyrians and too strong to be attacked by them, the kings of the Eighth Dynasty of Babylon had hitherto managed to remain free. Even Ashurnasirpal had spared the southern kingdom, giving his contemporary Nabû-apal-iddina (887 – 855 B.C.) time to repair some of the damage caused by the Aramaeans and the Sutû during ‘the time of confusion’. But in 850 B.C. hostilities broke out between King Marduk-zakir-shumi and his own brother backed by the Aramaeans. The Assyrians were called to the rescue. Shalmaneser defeated the rebels, entered Babylon, ‘the bond of heaven and earth, the abode of life’, offered sacrifices in Marduk’s temple, Esagila, as well as in the sanctuaries of Kutha and Barsippa, and treated the inhabitants of that holy land with extreme kindness:

For the people of Babylon and Barsippa, the protégés, the freemen of the great gods, he prepared a feast, he gave them food and wine, he clothed them in brightly coloured garments and presented them with gifts.

Then, advancing farther south into the ancient country of Sumer now occupied by the Chaldaeans (Kaldû), he stormed it and chased the enemies of Babylon ‘unto the shores of the sea they call Bitter River (nâr marratu)’, i.e. the Gulf. The whole affair, however, was but a police operation. Marduk-zakir-shumi swore allegiance to his protector but remained on his throne. The unity of Mesopotamia under Assyrian rule could perhaps have been achieved without much difficulty. For some untold reason – probably because he was too deeply engaged in the north and in the west – Shalmaneser did not claim more than nominal suzerainty, and all that Assyria gained was some territory and a couple of towns on its southern border. The Diyala to the south, the Euphrates to the west, the mountain ranges to the north and east now marked its limits. It was still a purely northern Mesopotamian kingdom, and the empire had yet to be conquered.

The end of Shalmaneser’s long reign was darkened by extremely serious internal disorders. One of his sons, Ashurdaninaplu, revolted and with him twenty-seven cities, including Assur, Nineveh, Arba’il (Erbil) and Arrapha (Kirkuk). The old king, who by then hardly left his palace in Nimrud, entrusted another of his sons, Shamshi-Adad, with the task of repressing the revolt, and for four years Assyria was in the throes of civil war.

The war was still raging when Shalmaneser died and Shamshi-Adad V ascended the throne (824 B.C.). With the new king began a period of Assyrian stagnation which lasted for nearly a century.