On 14 February, in the first crossings of the Irrawaddy, the boats of assault troops took fire from Japanese machine-gun pits high up in cliffs on the east bank. Among the casualties were men of a VCP unit who were sunk in midstream. Fortunately, another VCP section made it across with some of the leading infantry. Very quickly they were able to call up B-25 Mitchell bombers and P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers, which were circling overhead, to target Japanese positions.

Next day a ‘cab rank’ of fighter-bombers unleashed wave upon wave of high explosive and napalm onto enemy defenders. In many instances the accuracy achieved by the VCP’s liaison with the pilots reduced some of the IV Corps ground forces to stationary observers while the ferocious bombardment obliterated Japanese defenders. Within a few days the bridgehead was well established, and a force set out to race the 85 miles to Meiktila.

In the dry season conditions vehicles were able, at times, to drive six abreast and in the scrub even on either side of the road. It meant on occasions, however, that bulldozers had to be unloaded from trucks to drag vehicles out from the deep sand of dried-up chaungs. And all the time fighters from 221 Group scoured the skies, trying to keep enemy aircraft at a distance. Would the Japanese in Meiktila remain ignorant of this growing threat to their very survival? Incredibly, within seventy-two hours of departing Pagan, the lead formations of IV Corps had captured their first objective, Thabutkan, an outlying airfield of Meiktila.

To keep pace with Fourteenth Army, both the outflanking movement by IV Corps and the main crossings of the Irrawaddy farther north by Fourteenth Army, RAF fighter squadrons leapfrogged from one temporary airstrip to another to maintain the umbrella of air superiority. One of those was No. 17 Squadron RAF, commanded by Squadron Leader J.H. ‘Ginger’ Lacey which, on 3 February, moved from Tabingaung to Ywadon. Despite the disruption incurred from another relocation, daily defensive patrols in the Tabingaung-Budalin-Ywadon-Monya area continued, but no enemy aircraft were sighted. Two days earlier, on 1 February, at the Tabingaung airstrip an early morning JAAF raider had damaged two aircraft and, as they took ownership of their new airstrip at Ywadon, the threat of another enemy raid was a concern to Squadron Leader Lacey.

All sections were busy erecting tents, and digging slit trenches, which we considered very necessary after our experience at Tabingaung. The officers set up their sleeping quarters in a two-floor building, which had apparently been used by monks at one time, and had recently been vacated by the Japs. A dining room and bar are to be organised on the ground floor.

James Henry ‘Ginger’ Lacey was born on 1 February 1917 in Wetherby, Yorkshire. He left King James’ Grammar School in 1933, trained as a dispensing chemist and joined the RAFVR in 1937. He did initial training in Scotland, became a flying instructor at the Yorkshire Aeroplane Club and spent six weeks at RAF Tangmere before being called up at the outbreak of war. Lacey was posted as sergeant with No. 501 Squadron in France in 1940, where he claimed five victories to become an ace, was Mentioned in Despatches and awarded the Croix de Guerre.

In the Battle of Britain Lacey notched up more victories, despite surviving being shot down and baling out on at least three occasions, and received the DFM in August 1940. His name became well known on 13 September 1940, when a Heinkel He111 bombed Buckingham Palace. Lacey pursued it and shot it down over Maidstone, Kent, before he was unable to find his airfield in poor visibility, and was forced to bale out again. The publicity for this feat brought him the gift of the first silk parachute made in Australia, together with a silk scarf signed by a hundred workers at the factory which made it.

By October he had twenty victories, making him the top-scoring fighter pilot in the Battle of Britain. Lacey was commissioned in January 1941 and various postings as an instructor followed, which included 22 EFTS where one of his trainees was the eighteen-year-old trainee Gordon Conway who, with No. 136 Squadron, would apply Lacey’s teachings to also become an ace. In March 1943 Lacey was posted to Calcutta in India. After spells with Wing Commander Frank Carey at the Amarda Road Gunnery School, he moved to No. 155 Squadron, and, in November 1944, was appointed squadron leader in command of the Spitfire VIIIs of No. 17 Squadron.

In the days following No. 17 Squadron’s arrival at Ywadon, in the absence of any contact with enemy fighters, the daily defensive patrols took the opportunity to destroy and set on fire any Japanese vehicles and buildings that they could find. On 14 February No. 17 Squadron supported the two crossings of the Irrawaddy by IV Corps at Nyaungu and just south of Pakkoku. Under direction by a VCP, strafing attacks were made on buildings harbouring the enemy, and Japanese positions on an island in the Irrawaddy south-west of Pakkoku. At least one gun position was destroyed and a village left in flames.

Next day No. 17 Squadron was scrambled and vectored over Nyaungu to protect IV Corps crossings, only to learn later that sixteen Oscars had attacked Fourteenth Army’s front lines at Myinmu. During the morning and afternoon forty-two sorties were flown, and no contact made; it was that kind of day. In the evening they learned that No. 152 Squadron’s Spitfires had shot down a Dinah, provoking ‘Everyone very jealous’, from Squadron Leader Lacey.

Fortunes changed on 18 February when Lacey reported:

Really good news at last! Flying Officer Connel, while on an air test, shot down an enemy ‘Irving’ reconnaissance aircraft. We are also on full rations, and the food situation has improved enormously. The soccer team won its first game against the Servicing Commandos, 4–2.

The Irving was a Nakajima J1N Navy Type 2 land reconnaissance/fighter, and its demise, following the news of the destruction of a Dinah by No. 152 Squadron, showed how the Spitfires were denying the JAAF reconnaissance flights. The organizing of soccer matches perhaps also indicated the degree of air supremacy now being enjoyed.

The domination over the JAAF was reinforced on 19 February when Squadron Leader Lacey shot down an Oscar II, which brought his confirmed victories to twenty-eight enemy aircraft destroyed. In addition, Pilot Officer F.D. Irvine made his first kill of an Oscar and Flight Lieutenant E.H. Marshall claimed a probable, making Lacey more than pleased.

Another great day! A signal was received in the evening from Group Captain Findlay, which read, ‘Congratulations on two days good work – keep cracking.’ To top it all an authority was received to draw a beer ration, and there was much celebration in the messes.

In contrast, on the evening of 22 February a gramophone recital of a Beethoven symphony was held in the dining tent where a large audience adjudged it a great success. On 24 February a VIP flight was escorted out of Monya and defensive patrols carried out in the Pakkoku and Myinmu areas. During one of those patrols south of Taungtha Flying Officer Rutherford and Flight Sergeant Travers drove off twelve Oscars, which were about to attack a concentration of Fourteenth Army motor vehicles and tanks. Flying Officer Rutherford probably destroyed one Oscar, which was seen losing height, smoking, and with two other Oscars fleeing in the direction of its base. That just two Spitfires could disrupt and scatter twelve Oscars, was a stark illustration of the status of the Spitfire VIII as the top predator of the skies.

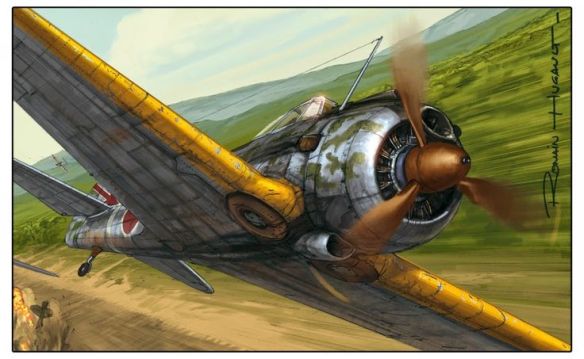

Thirty patrols were undertaken by No. 17 Squadron on 26 February over the IV Corps bridgeheads at Nyaungu and south of Pakkoku, one of which demonstrated that there was still some fight left in the JAAF. In the 09.45 patrol in the Mahlaing area, Flying Officer W.J. Detlor and Sergeant F. Holland were jumped by more than six Oscar IIs, Nakajima Ki-43-II fighters with an upgraded engine and a three-bladed propellor. Owing to the haze and the enemy aircraft coming out of the sun, Detlor and Holland were forced to take desperate evasive action to shake off the Oscars.

The intensity of operations over February and preceding months caught up with No. 17 Squadron on 28 February. A servicing backlog, exacerbated by difficulties in the relocation from Tabingaung, meant that only two aircraft were able to undertake patrols. Squadron Leader Lacey took the opportunity to relieve the pressure on the squadron’s pilots, and accompanied a contingent on a visit to the nearby Myin-Gwya Monastery, which was one of the largest in Burma.

We were entertained to Tiffin by the High Priest, and the Supervisor of the Burma Post and Telegraph, who had been hiding there during the Japanese occupation.

The report by Squadron Leader Lacey for February 1945 provides an insight typical of the experience and demands of the Spitfire squadrons as they strove to keep pace with Fourteenth Army and maintain the protection and air superiority which was so essential.

On the three occasions when the Japanese air force made an appearance and we managed to engage their aircraft, we gave them a trouncing. We have added three confirmed victories and one probable to the 17 Squadron scoreboard, and needless to say morale is excellent. The Squadron created a record of 1,300 operational hours from 758 sorties in spite of it being a 28 day month.

When the Squadron moved to Ywadon, again the transport arrangements were equally as badly organised as on the previous occasion. Eventually, as DCs were not forthcoming, we had to complete the move ourselves by sending 3-tonner motor vehicles back to Tabingaung to pick up the remaining equipment and personnel. Quiz competitions and mobile cinema shows helped to fill in time on some evenings, but the non-arrival of the month’s beer ration was disappointing to say the least.

In support of Fourteenth Army the Squadron destroyed or damaged: one tank, three motor vehicles, and a staff car, the crews of which were killed, ten bullock carts carrying petrol drums, Japanese field-gun positions and buildings. In addition there were attacks on Japanese positions at Nyaungu and near Pakkoku on the Irrawaddy river, where IV Corps were crossing.

The quarantining and hiding of the real scale of the advance of IV Corps by the aircraft of No. 221 Group from any sighting by Japanese aerial reconnaissance aircraft had been an unqualified success. In retrospect it almost seems too good to be true. General Slim acknowledged this critical achievement, which was fundamental for his strategy.

throughout daylight Vincent’s fighters patrolled over the route, and as far as I know no Japanese scout ever penetrated his screen, without being shot down for his daring.

Even after IV Corps had crossed the Irrawaddy, the Japanese General Kimura, deprived of air reconnaissance information, still believed it to be a minor attack. He thought the bulk of IV Corps to be still in the north and was therefore concentrating his forces at Myinmu. When IV Corps reached Meiktila, Kimura was forced to abandon this plan and attempted to move south to counter the capture of Meiktila’s airfield at Thabutkan. Kimura threw everything he could at the IV Corps positions at Thabutkan and targeted his artillery at the arrivals of Dakota transport aircraft.

Before the landing of every flight at Thabutkan, troops of the RAF Regiment, who had accompanied IV Corps, made a sweep of the airfield and its vicinity to clear Japanese incursions and snipers. These sweep operations by 400 men of the RAF Regiment took up to two hours to complete. On one operation they encountered an estimated two companies of Japanese troops, whom they drove back in a firefight, leaving forty-eight of the enemy dead for the loss of seven of their own. As the planes brought in a full brigade of troops from Imphal to bolster IV Corps, the struggle to hold Thabutkon airfield went on for week after week until, on 22 March, disaster hit, when seven Dakotas were destroyed by Japanese shelling.

All flights were suspended, and doubts as to whether IV Corps could hold out were intensified. Parachute drops continued but landings by Dakotas did not resume until early April. Even then some enemy shells were bursting 200 yards from the runway. Eventually the remaining enemy defenders were cleared from the vicinity of Thabutkon airfield; Japanese forces were then killed or driven from the desolated town of Meiktila, and its main airfield occupied. Many dead enemy troops could be seen floating in the nearby lake. This allowed Allied planes to begin using the main airfield at Meiktila, from where ironically in the past JAAF aircraft had taken off to raid Imphal and Kohima.

The capture of Meiktila and its airfields secured the proverbial anvil. It was the pivotal turning point for the battle for Burma. With IV Corps and No. 221 Group in possession of Meiktila, and some 80 miles south of Mandalay on the route to Rangoon, the Japanese Army was cut in two. Meiktila would now be the anvil against which XXXIII Corps and No. 221 Group would smash the Japanese forces. The lynchpin of the whole Allied strategy for retaking Burma before the monsoon was in place. Or was it?