The spirit of revolt in 1296 was far-reaching; just as the untimely death of Alexander III in 1286 had deprived the nobles and the Community of the Realm of a figurehead on whom the functioning of the feudal system depended, the Scottish nobles had taken a dangerous step in dismissing John Balliol as their lawful king. Men such as Sir John de Graham, John Comyn, 2nd Lord of Badenoch, John Comyn, 3rd Earl of Buchan, Sir John de Soulis, Sir Andrew Murray of Bothwell, John de Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl, Alexander, Earl of Menteith, Bishop William Lamberton of St Andrews and Bishop William Wishart of Glasgow were determined to resist the invader even without a resolute king to lead them in battle.

In April 1296 Patrick, 8th Earl of Dunbar was in Berwick, attending the war council convened by Edward I when news arrived there that Dunbar’s Countess Marjorie Comyn had handed over his castle to her brother, John Comyn of Buchan. Dunbar, who lived in perpetual fear and awe of Edward I, was devastated; not only had he lost face on account of his wife’s insolent act, but his pledge to hand over Dunbar Castle to Edward as a base for operations in the south-east was broken. Nothing appears to have been recorded about Edward’s views on the matter but, doubtless, he held Dunbar in contempt and would have shown it. No matter, he detached a portion of his large army under the command of John de Warenne, 7th Earl of Surrey, and William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick, the latter a veteran of Edward’s campaigns in Wales. Warenne and Warwick were given express orders to relieve Dunbar Castle; on 25 April, they marched out of Berwick with a force of 1,000 heavy cavalry and 10,000 infantry. It is not known if the Earl of Dunbar accompanied them.

Countess Marjorie Dunbar, daughter of the late Alexander Comyn, 2nd Earl of Buchan did not share her husband’s enthusiasm for Edward I. Whether she acted on impulse or was persuaded by her Comyn kinsmen to give up Dunbar Castle is not recorded; it is more than likely that, appalled by the reports of the massacre at Berwick, she decided to support her kinsmen. (According to one source the Earl of Mar declared Patrick Dunbar a traitor and persuaded Marjorie to surrender his castle as a matter of honour.) Dunbar’s brother Alexander, who was in command of the castle, knew he could not hold out against the Comyns with his pitifully small garrison; on 25 April he surrendered the castle to the patriots.

Dunbar Castle was placed in the charge of Sir Richard Siward, a man renowned and respected in feats of arms. Warenne and Warwick arrived at Dunbar Castle on 26 April and immediately laid siege to it from both land and sea. For a day the defenders did little more than glower at the besieging forces until Warenne learnt that the Scottish host commanded by the Comyns of Badenoch and Buchan was camped at the foot of Doon Hill, which overlooks Dunbar. Warenne left the siege of the castle to a few junior officers in command of a token force as he knew the garrison was hardly able to sally out; Siward and his defenders were going nowhere, expecting Warenne and Warwick to be defeated by the Comyns. Warenne led the bulk of his force, intent on engaging the Scottish host which he knew was camped about two miles south of Dunbar.

According to English chroniclers of the day the Scottish host numbered 40,000; the figure was probably closer to 4,000, with Warenne’s 10,000 nearer 1,000. Contemporary accounts tended to exaggerate the strengths of armies to make the victors more victorious, the defeated ignominious; it is thought that each army at Dunbar and in other conflicts was a tenth of the figures given by the chroniclers, a fact which many modern historians support. Whatever the precise strengths of the Scottish and English armies, the Comyns outnumbered Warenne and Warwick by four to one at least.

It is not entirely certain where the battle was fought. Some historians consider it took place near a part of Spott Glen in the vicinity of a farm called The Standards for obvious reasons. One has to question whether the name dates as far back as 1296. However, more recent research suggests the battle took place near Wester Broomhouse which is within a bowshot or two of Spott Glen and its continuation, Oswald Dean. The valley, a deep defile formed by glacial activity, runs from the east of Spott village to Broxmouth on the coast. It is a picturesque glen, watered by a small, unimpressive burn or stream; its sides are steep, covered by straggles of gorse and stunted, windswept hawthorn bushes. In spring it is a bleak place which even a profusion of primroses fails to soften. It was in this obscure glen that cold steel would determine the fate of King John Balliol and the nation of Scotland.

The Scottish host was camped on or near Doon Hill. On the morning of 27 April, Comyn of Badenoch would have easily discerned the approach of Warenne’s army, marching to Wester Broomhouse on the road to Spott Village. The dust raised by the men and horses would have pinpointed the English advance for more than a mile. The Scots waited, confident in the superiority of their numbers; however, apart from the fact that their largely untrained army was unaccustomed to warfare, it also lacked heavy cavalry and archers, crucial elements that day and in many to come in the Wars of Independence.

On that cold but bright spring day any flocks of sheep or cattle grazing in Spott Glen would have been driven away to safer fields. The English came on relentlessly, confident of victory and marching in good order. When Warenne reached Spott Glen or Oswald Dean the forward ‘battles’, as the medieval group formations – comparable to modern infantry battalions – were then known, descended into ‘a valley’ to form their line of battle. Changing from column to line was a delicate business; the most effective way of deploying an army into battle formation was to march it on to the field with units of the column wheeling right until the entire force was ordered to halt and then turn left to form a line facing the enemy. Although this sounds simple it would have been difficult to execute in the narrow confines of Oswald Dean. During this deploying movement the Scots thought Warenne was retreating.

Comyn of Badenoch appears to have planned no strategy or tactics other than to mount a frontal attack on the English; few if any troops were kept in reserve. For his part Warenne knew that his numerically inferior force would be hard-pressed to rebuff a frontal assault made by the superior number of Scots on the higher ground at the base of Doon Hill. He deployed his troops carefully, posting archers among the infantry in the front line; it was his intention to engage the Scottish left or right wing, then roll up the centre, a tactic Oliver Cromwell would use at Dunbar in 1650.

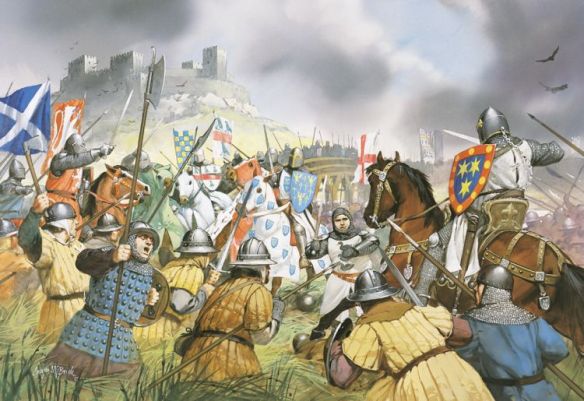

We can imagine the scene at Oswald Dean on that cold April day. Steel reflecting the weak sunshine, the only sound being that of neighing horses and the English pennons and banners snapping in the stiff wind that blew along the narrow valley. From his vantage point on Doon Hill Comyn of Badenoch had watched Warenne deploy his men; observing no further movement in the serried ranks of the English army, he ordered a full attack, launched from his strong position on the hill. (History would repeat itself in 1650). The Scottish van was packed with men and boys eager to engage the enemy; the undisciplined mass charged across the plain at the foot of Doon Hill, then down the slopes of Oswald Dean, blowing their horns to encourage those who followed. The precipitate charge was a disaster.

The unruly, screaming horde of peasants armed with inferior weapons – spades, scythes, axes and pitchforks – did not in the least confound the ranks of Warenne’s disciplined professionals. Warenne protected his flanks with his 1,000 cavalry, with archers interspersed among the front-line infantry. That day the English fought under the banner of Edward I and their protecting saints – John of Beverley, Cuthbert of Durham and Wilfrid of York.

The English infantry stood fast, confident that their flanks were well protected by the horse which could quickly deploy and scatter any Scots who attempted to get behind them. The infantry and archers, observing the undisciplined mob that was the Scottish vanguard, let confusion do their work for them. Too many men in a confined space at Oswald Dean reduced the effect of Comyn’s superiority in numbers, turning it to disadvantage. The order was given for the English archers to loose their deadly arrows that surely must have filled the sky. The shafts could scarcely fail to find a mark among the ragged mob leaping over Spott Burn in tightly packed, undisciplined bunches.

The foremost elements of the Scottish host were cut down in minutes, if not seconds; the fallen hindered the progress of those who followed. Dead and wounded began to pile up on the green sward. The tide of battle did not even remotely threaten the English foot, commanded by dismounted knights who no doubt stiffened their resolve by standing alongside their men, taunting the Scots. A welter of blood soon began to stain the turf at Oswald Dean.

The agony was over in less than half an hour. Hundreds – thousands, if the English chronicles of the day can be trusted – of dead eyes stared at the sky that dreadful April day. The English chroniclers numbered the Scottish dead in their thousands – 10,055, a suspiciously precise and high figure, even given the devastation wreaked by the English archers. We have little choice but to accept the contemporary English accounts, although it is often said that, in battle, the victors write the history. It made good propaganda for home consumption. Warenne’s army had been out-numbered, yet he had prevailed. There does not appear to be any record of the English casualties.

The shattered bands of survivors ran from the field, seeking refuge in the Border forests, leaving their wounded at the mercy of Warenne’s men. Among the undoubtedly numerous slain was Sir Patrick de Graham of Montrose who gave and expected no quarter; he alone was praised by the English for valiantly standing his ground. Another noble, Walter, Earl of Menteith, was taken prisoner and executed on Edward I’s orders; other prisoners included the Earls of Atholl and Ross, members of the oldest Celtic noble families in Scotland. Dunbar Castle surrendered the same day as the battle; sheltering within its walls were Sir Richard Siward, John ‘the Red’ Comyn, son of Comyn of Badenoch and many other ransomable notables. More than 100 knights were taken into captivity in chains; they were sent to no fewer than twenty-five castles in England, the most prestigious including the Red Comyn – and valuable in terms of ransom money – being imprisoned in the Tower of London.

As for Countess Marjorie, doubtless she was rebuked by her husband, Patrick, Earl of Dunbar for her contumacy although the marriage survived. As far as is known, no such rebuke came from Edward I; in point of fact, Edward showed an unusual clemency towards the wives and daughters of those taken prisoner in Dunbar Castle, even to the extent of awarding them pensions. The English king could be chivalrous when it suited him.

After the battle of Dunbar, Edward I conquered Scotland with almost derogatory ease. Scottish resistance collapsed like a house of cards. In the subsequent weeks the castles of Roxburgh, Edinburgh, Perth and Stirling surrendered. As for his part, King John Balliol – ex-king in Edward’s eyes – sent the English king a grovelling letter in which he confessed his fault, blaming his actions on false counsel. He apparently renounced the Treaty of Paris – the Auld Alliance – but this failed to pacify Edward; he was determined to humiliate Balliol to serve as a warning to any others attempting to gain the throne of Scotland and rise in rebellion. Balliol was attended by John Comyn, 3rd Earl of Buchan at Montrose Castle, where, on 5 July, Balliol surrendered to Edward. When the English king learnt of the alliance Balliol had made with France he was enraged. In an ignominious ceremony, Edward stripped the hapless king of his royal trappings; this involved the physical removal of Balliol’s tabard – a knight’s decorated outer garment worn over armour and blazoned with his coat of arms – his hood and knightly girdle, a punishment usually meted out to a knight found guilty of treason. Balliol became known in Scotland’s history as Toom Tabard (Empty Coat); he was taken to the Tower of London along with his closest advisers, there to languish for a time before he was exiled to France, where he died in obscurity a few years later.

Edward was determined to strip Scotland herself of any symbols of her right to independence, along with every document held in the national archive supporting this claim. The Stone of Destiny at Scone, where many Scottish monarchs were crowned, the Holy Rood, the personal relic of Scotland’s only saint, Margaret, wife of Malcolm III, and many documents were taken over the Border. The Great Seal of Scotland (Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum) was broken up. This act tellingly revealed Edward’s utter contempt for the country; on destroying the seal, Edward is supposed to have commented that ‘a man does good business when he rids himself of a turd’.

Edward’s sojourn in Scotland did not last long. The country was prostrated; Edward appointed John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, as governor of Scotland and Hugh Cressingham as its treasurer. There is an interesting account of Edward’s brief stay at Dunbar which goes thus:

On the day of St George, 24 [sic] April [1296] (St George’s Day is actually 23 April), news came to the king that they of Scotland had besieged the Castle of Dunbar, which belonged to the earl [sic] Patrick, who held strongly with the king of England. It was upon a Monday that the king sent his troops to raise the siege. Before they came there, the castle had surrendered and they of Scotland were within when the troops of the king of England came there. They besieged the castle with three hosts on the Tuesday that they arrived before it. On the Wednesday, they who were within sent out privately [i.e. sent couriers to John Comyn, leader of the Scottish army] and on the Thursday and Friday came the host of Scotland all the afternoon to have raised the siege of the Englishmen. And when the Englishmen saw the Scotchmen [sic] they fell upon them and discomfited the Scotchmen, and the chase continued more than five leagues [about fifteen miles] of way, and until the hours of vespers [evening prayers] and there died sir [sic] Patrick de Graham, a great lord, and 10,055 by right reckoning. On the same Friday by night, the king came from Berwick to go to Dunbar, and lay that night at Coldingham [Priory] and on the Saturday [28 April] at Dunbar and on the same day they of the castle surrendered themselves to the king’s pleasure. And there were the earl [sic] of Atholl, the earl of Ross, the earl of Menteith, sir [sic] John [the Red] Comyn of Badenoch, sir Richard Suart [Siward], sir William de Saintler [Sinclair] and as many as fourscore [sic] men-at-arms and sevenscore footmen. There tarried the king three days.

The message that came loud and clear from the battle of Dunbar in 1296 was that patriotism alone was not enough. Edward had, however, forged a dangerous weapon. The rise of a strong and determined Nationalism would in time create a cohesive political and military force that would resist the kings of England for the next three centuries.

Edward I conquered Scotland in five months – April to August 1296, considerably less than the three wars over two decades he took to subdue Wales. In a parliament convened at Berwick on 28 August 1296, Edward made the final arrangements for the governing of Scotland. This time there would be no puppet king to interfere with whatever policy he might choose to adopt. In addition to Warenne and Cressingham, William Ormsby was appointed as Justiciar, or high judge. Edward also demanded the presence of every significant landowner in Scotland to pay him homage, accepting him as their liege lord. About 1,900 barons, knights and ecclesiastics answered his summons and attached their seals to what became known as the Ragman’s Roll, so-named because it was festooned with waxen or lead endorsements. The names of Robert Bruce the Elder and Bruce the Younger appear which is of some significance; much more important were those signatures which are absent – notably that of William Wallace, knight of Elderslie, who in 1297, in the brief but stirring words of the historian John of Fordun, ‘lifted up his head’.

Until 1296, Wallace was an obscure squire, living on the small estate of Elderslie, near Renfrew. His elder brother Malcolm held the land but the absence of their names from Ragman’s Roll is surprising. Lesser men than the Wallaces saw fit to sign the roll and swear an oath of allegiance, so it cannot be said that the Wallaces were considered lowly.

It is probable that the family de Waleys was of Norman origin who came to England with William the Conqueror in 1066. William was the younger son of Sir Malcolm Wallace of Elderslie by marriage to Margaret, daughter of Sir Reynold Crawford, Sheriff of Ayr. William was born in c.1270; little of his life is known to us save through The Actis and Deidis of the Illustere and Vailzeand Campioun Schir William Walleis, Knicht of Elderslie (Acts and Deeds of the Illustrious and Valiant Champion, Sir William Wallace etc.) by Henry the Minstrel, better known as Blind Harry. Written two centuries after Wallace’s death, Blind Harry’s account owes more to romantic fiction than fact which obliges us to rely on the equally imperfect and heavily biased accounts of contemporary English chroniclers.

William Wallace’s name comes to us first in 1297 when he appears to have been at odds with the by now occupying English administrators. Matters came to a head in May 1297, when the English murdered Wallace’s common-law wife, Marion or Marron Braidfute; in revenge, Wallace slew William de Hazelrig, Sheriff of Lanark. In the same month Warenne and Cressingham were absent on business in England; Justiciar Ormsby was holding court at Scone when Wallace and his small following broke into the place, looted it and very nearly took Ormsby prisoner. The idea persists that Wallace and his men were landless peasants, virtual outlaws, but this was not entirely the case. What mattered was that Wallace had shown the Scottish nobility it was possible to challenge England’s authority and succeed. Contemporary English chroniclers certainly portray Wallace as an outlaw, a view echoed by Patrick, 8th Earl of Dunbar who, if we can believe Blind Harry, reputedly said this of him:

This king of Kyll I can nocht understand

Of him I held niver a fur [long] of land.

It is thought that Kyll may derive from the Celtic coille, meaning a wood; Dunbar is therefore describing Wallace as a kind of Robin Hood, an outlaw of the forest.

While we rightly acknowledge Wallace as the dedicated, unflinching patriot that he undoubtedly remains in Scotland to this day, key leaders of the revolt against England were two of the former Guardians, Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow and James the Steward, the latter being Wallace’s feudal superior. They were joined by MacDuff, son of the Earl of Fife and Bruce the Younger, Earl of Carrick. After a farcical encounter with the English at Irvine in Ayrshire, Wishart and the Steward surrendered to the English commander. To his discredit, Bruce the Younger turned his coat for Edward I; he would continue in this fashion for nearly a decade, shifting his political position like a weather vane driven by the winds of change.

Only in the north was the revolt gaining momentum. Andrew Murray, son of a leading baron in Morayshire, was gaining a reputation for his bold and successful resistance to England’s authority. Murray and his father had been prominent on the field of Dunbar in April 1296; both had been taken prisoner but the younger Murray escaped from his prison in Chester Castle intent on continuing the fight. By early autumn 1297 the series of isolated outbreaks against English authority had become co-ordinated.

During the summer of 1297 Wallace had engaged in a period of intensive training of his raw levies; he taught them discipline and how to fight in schiltrons, tightly packed circular formations of men with long spears, the only effective defence against the English heavy cavalry. Because of Murray’s and Wallace’s successes, they were made joint Guardians of Scotland, acknowledged as ‘commanders of the army of the kingdom of Scotland and the Community of the Realm’.