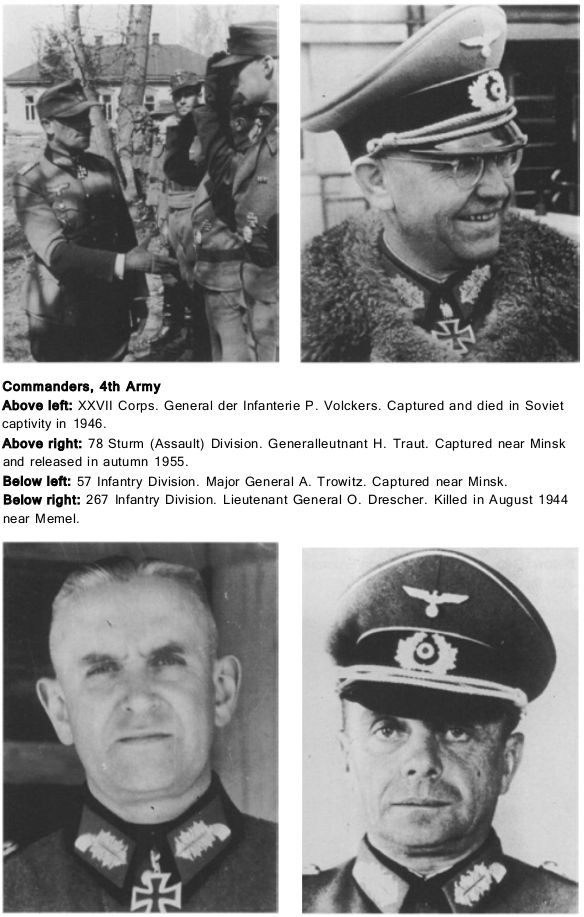

A large pocket had formed near Pekalin, south of Smolovichi to the east of Minsk, and this held three complete divisions, 57th, 267th and 31st, and remnants of 260th, 25th Panzer Grenadier and 78th Sturm Divisions – in fact most of the original formations of XII Corps. The six divisional com- manders were all present, together with the corps commander Lieutenant-General Vincenz Müller and the commander of XXVII Corps, General of Infantry Paul Völckers. There were also elements of XXVII Corps in the pocket. Some of these divisions were still strongly armed: 25th Panzer Grenadier Division had brought a staggering total of no less than 32 assault and 20 self-propelled guns. But although there had been an air resupply of fuel, ammunition was very short – not more than 5-10 rounds per gun.

On 5 July 1944 the two corps commanders held a General Officers’ conference to assess the situation and to decide upon future action. The overriding fact was that the nearest German lines were more than 100 kilometres to the west, and this seemed an impossible distance for their weary troops to cover without strong Luftwaffe support. Without fuel or ammunition they could not use their heavy weapons so the idea of a breakout seemed hopeless, but the thought of falling into Russian hands made any risk seem worthwhile. Major-General Adolf Trowitz, who had escaped from the Cherkassy pocket with his 57th Infantry Division during the previous winter, agreed to this, as did Major-General Günther Klammt of 260th Division. Lieutenant-General Hans Traut was undecided because of the wounded, probably numbering as many as 5,000, who would have to be abandoned. The decision was made to break out in two corps groups, XXVII Corps to the west and XII Corps to the north-west. The remaining formations of XXXIX Panzer Corps were allocated to the other two Corps. The decision was taken during the evening, despite General Völcker’s strong recommendation to stand and fight.

The breakout began at 2359 hours with 25th Panzer Grenadier Division striking out to the west towards Dzerzhinsk, south-west of Minsk. The wounded were left in charge of a doctor with a letter appealing to the Soviet commander to treat the wounded in accordance with the Rules of War. It is not known whether this had any effect. Having fired their last rounds, the gunners destroyed their weapons. The three groups charged with the bayonet shouting ‘Hurrah!’ Despite very heavy fire, Lieutenant-General Paul Schürmann got out with his group after overpowering a Soviet battery, but with only 100 men left out of his original 1,000. The Soviets now counter-attacked and the groups were split up into smaller groups, all trying to make their way to the west. Apparently some succeeded because Schürmann was not captured and the division was reformed in Germany later in the year.

General Trowitz’s 57th Infantry Division broke out the same evening but was almost immediately hit by heavy fire. The columns retained their cohesion and joined up with the remnant of ‘Feldherrnhalle’ Division at dawn on the 6th. The two divisional commanders decided to act together to cross the Cherven—Minsk road which was held by Soviet forces. The two divisions waited until nightfall before moving. ‘Feldherrnhalle’ was scattered and most of its men were captured. Once across the road 57th Division, which still numbered 12—15,000 men, split up into smaller groups. The divisional commander’s group, the last to cross the road, had two VW Schwimmwagen to carry the wounded. At daylight the group found itself in the midst of a network of Soviet positions and decided to wait for nightfall before moving again. They took cover in a field of rye and the exhausted men fell asleep until early evening when they were woken by rifle and mortar fire. One by one the small groups were taken prisoner. General Trowitz and the remaining groups were rounded up during the next two days.

General Traut’s 78th Sturm Division had a similar fate. A survivor gave the following account: ‘The troops formed up for the assault at 2300. Individual units began to sing the ‘Deutschlandlied’ [the German national anthem]. The survivors will never forget that night. Burning villages, howitzer and rifle fire, dull explosions mixing with the thunderous shouts and singing of the attacking units. Enemy forces which tried to resist were overrun and surrounded again. The breakout succeeded …

‘By dawn of 6 July the enemy encircling positions had been left behind. However, the scattered Russian units quickly regrouped. Enemy motorized forces arrived. The larger breakout groups were soon caught and surrounded again. The only chance was to break up into very small groups.’ Most of 78th Sturm including their divisional commander General Traut were captured.

This story was repeated with different emphasis by all the divisions that tried to break out from the pocket. The order issued by Lieutenant-General Otto Drescher to his 267th Infantry Division read: ‘Soldiers of my victorious 267th Infantry Division. While enemy penetrations in the sector of Army Group Centre made a withdrawal inevitable, the enemy brought forward strong forces on 3rd and 4th July against XII Corps. Our division acted as the rearguard of the Corps and successfully repelled all attacks, allowing the other divisions to withdraw safely. You, the soldiers of my division, have proved your valour and heroism in your commitment to the soldiers in the other Divisions.

‘During this battle the enemy succeeded in encircling our troops. This encirclement must be broken and we must fight our way to freedom and to our homeland. If we are to see our homeland and families again, we must fight. I want no one to doubt that the way will be difficult and great sacrifice will be required. Whoever prefers the dishonourable fate of captivity will be subjected to the habitual cruelty of the Bolshevik murderers. I have no doubt that the choice will not be difficult. On comrades! On to the decisive attack, back to freedom and our homeland! Drescher.’

Among the measures ordered by General Drescher were careful evaluation of reconnaissance reports; preparation of copies of a good scale map with wide distribution; silent destruction of vehicles, guns and even the battalion cooking equipment; and the formation of a cavalry squadron from artillery horses. All troops, where ever they came from, were taken into the combat groups, and weapons were distributed equally.

The 267th Infantry Division broke out in three columns, their first objective being to cross the Orsha—Minsk railway, and then the main road, which was protected by infantry posts. The left-hand column crossed both the railway and the highway, but Soviet armour arrived and fired at random into the dense mass of troops. Resistance was pointless and this column sur- rendered. Some of them later managed to escape to the west. The rout of the right-hand column led through dense forest infested with partisans, and the column split into smaller groups. Those that were captured were marched by the partisans along the highway to Borisov.

The remaining groups struggled on to the north-west. Some were attacked by two Soviet infantry companies supported by mortars. The Germans, who had only their rifles with not more than ten rounds per man, fought valiantly but to no end; all were either killed, or captured and sent to Borisov.

A Soviet senior lieutenant who was captured by the Germans made this statement: ‘East of Minsk, I saw two columns of German prisoners of war, about 400 to 600 men, marching in the direction of Moscow. The majority of the prisoners were barefoot. In spite of the heat, they were allowed no water from the local streams during the march, therefore they drank muddy water. Whoever staggered was beaten, if a prisoner collapsed, he was shot. Once I saw a row of executed German prisoners lying in a roadside ditch. When they passed through a town, they would beg for bread, but the civilians did not dare give them any. I saw a German senior lieutenant sitting on the edge of a trench. He wore a uniform shirt with shoulder insignia and bravery awards, but he had no trousers and was barefoot. The guards removed the better clothes from the prisoners, in order to trade them for liquor with the civilian population.’

The central column under personal command of General Drescher fared rather better. They crossed the railway as well as the highway and on the first day made considerable progress to the north-west in the direction of Molodechno. As food was now in very short supply and everyone would have to exist on what could be found in the forest, General Drescher decided to split the columns to make foraging easier. He then laid down the direction to be followed by each group and ensured that each had a commander with some experience of orienteering. Even the divisional chaplain was given a group of 100 men to lead. During the march many groups were split up even more, either of their own volition or because of swamps or partisan activity. Most of them were killed or captured, but as comparatively few captives returned the details of their fate will never be known.

One of the most successful columns was that of 25th Panzer Grenadier Division led by General Schürmann, the first to leave after the commanders’ conference. As we have seen, the main group split up during the actual breakout, but his group went on to cross the Bobruisk—Minsk railway line which was already covered by the Soviets. He then attempted to cross more outpost lines without success and decided to turn eastwards and bypass Minsk to the north. This was successful and he managed to lead his ever dwindling detachment, which now numbered only 30 men, to the German lines north of Molodechno and south of Vilnius. His was the largest group to reach the German lines. The remnant of the Division was withdrawn to the training area in Bavaria. It was then employed in the west until the Ardennes offensive failed when it was sent to help defend Berlin. General Schürmann remained with the Division until February 1945.

It is interesting to look at the breakout phase from the Soviet point of view. The following is an extract from the Soviet Military History Journal published in 1984, which describes the outline of the reduction of the German encirclements and breakout groups: ‘The actions to eliminate the surrounded enemy in the area to the east of Minsk can be conditionally divided into three stages which are characterized by the use of different methods. Thus, in the first stage [from 4 to 7 July] the enemy endeavoured to break out to the west in an organized manner, with the chain of command still intact and receiving some air supply. During this period our troops made concentrated attacks to split the enemy groups into smaller parties, and forced them to abandon heavy military equipment and weapons. In the second stage [to 9 July] individual Nazi detachments were still endeavouring to put up organized resistance, advancing along forest roads and paths and attempting to escape from encirclement. The Soviet troops destroyed these isolated groups by intercepting them on advantageous lines and destroying them with fire and attack by the main forces of divisions and regiments. In the third stage [9 to 11 July], the scattered small enemy groups, now chaotic and without organized resistance, endeavoured to break out of the snare to the west. The Soviet forces ‘combed’ the forests and fields and captured small enemy groups, using small composite detachments (a rifle company or battalion reinforced by a tank platoon, a battery of anti-tank guns and a mortar company) mounted on motor vehicles.’

In the various accounts the impression is given that some of the German generals were lukewarm about continuing the unequal struggle. This appears to be the line they took at the commanders’ conference on 5 July. The foremost among these appears to have been General Vincenz Müller, the commander of XII Corps and acting commander of Fourth Army. One day, during the breakout, a German officer carrying a white flag appeared in the Soviet lines saying that an important German general wished to meet a Soviet general of equal seniority, to discuss the surrender of his troops.

This was General Müller who gave ‘the impression of a sullen, depressed man in untidy uniform with only one shoulder-strap and his boots were dirty. General Smirnov, the commander of the Soviet 121st Infantry Corps, asked him if he wanted to tidy himself up. He answered “Yes, thank you.” The general was taken to a separate house. After he had tidied himself, he came out accompanied by his orderly.’ It was then suggested to General Müller that he write an order instructing his soldiers to lay down their arms. This would then be scattered over the area by Soviet aircraft. Müller agreed with this and added that he did not want the blood of his soldiers to be spilt.”