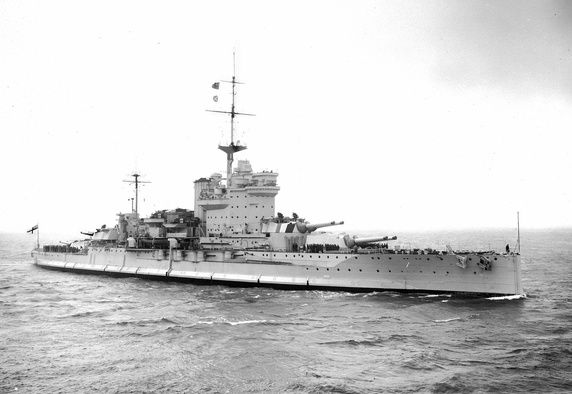

During the Battle of Calabria on 9 July 1940 Warspite achieved one of the longest range gunnery hits from a moving ship to a moving target in history, hitting Giulio Cesare at a range of approximately 24 km (26,000 yd).

Punta Stilo and Taranto

Soon afterwards, the first naval engagement between the British and the Italians occurred at the Battle of Punta Stilo [ Battle of Calabria], after the submarine HMS Phoenix had alerted Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, that the Italians had two battleships at sea. On 8 July 1940, the two ships were 200 miles east of Malta and steaming on a southerly course. Aerial reconnaissance later found that the two warships were supported by six cruisers and seven destroyers, escorting a large convoy. Cunningham planned to put his ships between the Italians and the major forward base at Taranto.

The following day, a Malta-based flying boat found the Italians 145 miles west of the Mediterranean Fleet at 0730. Further confirmation came from aircraft flown off from Eagle. By noon, the distance had closed to 80 miles and it was not until then that the Italian Admiral, Campioni, was alerted to the proximity of the Mediterranean Fleet by a seaplane catapulted from his own ship, the Guilio Cesare.

Other than Cunningham’s flagship, Warspite, most of the British ships were outgunned. To slow the Italians down, two strikes by Swordfish armed with torpedoes were launched from Eagle, but failed to score any hits, missing the opportunity to slow the larger ships, or even sink a cruiser. Just before 1500 hrs, two British cruisers spotted four of the Italian cruisers, which responded with their 8-inch main armament, outgunning their British counterparts which only had 6-inch guns. Cunningham, ahead of his other two battleships in Warspite, raced to the rescue and opened fire at just under 15 miles, forcing the Italians back behind a smokescreen. While Eagle and the two older battleships tried to catch up, two Italian heavy cruisers attempted to attack the carrier, drawing further fire from Warspite, Malaya and Royal Sovereign. At 1600, the two fleets’ battleships were within sight of one another and Warspite opened fire again at a range of nearly 15 miles, almost immediately after the second Swordfish strike. The Italians replied with ranging shots straddling the British ships, but a direct hit on the Guilio Cesare at the base of its funnels by a salvo of 15-inch shells persuaded the Italians to break off the engagement under cover of a heavy smokescreen. Cunningham also turned, aware that his ships would not be able to catch the Italian ships and that there was the risk of submarine attack. Italian bombers finally arriving to attack the Mediterranean Fleet bombed their own ships by mistake, to the delight of the crew of Warspite’s Swordfish floatplane, in the air since before the start of the action.

This was the only battle in the Second World War when two full battle fleets actually engaged.

An attack on the Italian fleet in its forward base at Taranto had been planned some years before the Second World War broke out at the height of the Abyssinian crisis in 1935, when the Mediterranean Fleet aircraft carrier was Glorious. The plan was revived in 1940. Originally it was intended that two carriers, Illustrious, newly arrived in the Mediterranean, and Eagle, should be used, giving a total of thirty Fairey Swordfish biplanes for the operation. A serious hangar fire aboard Illustrious delayed the operation, and then Eagle, having suffered extensive damage to her aviation fuel system as a result of near misses by heavy bombs, was not available. A number of aircraft were transferred from Eagle’s squadrons to those aboard Illustrious, giving a total of twenty-four aircraft for the operation, but before the operation could begin, two aircraft were lost. In the end, just twenty-one aircraft were available.

The operation eventually took place on the night of 11/12 November 1940, in two waves, with twelve aircraft in the first wave and nine in the second. Attacking against a heavily defended target, the first wave concentrated on the ships and the second wave on the shore installations. Three of the Italian Navy’s six battleships were sitting on the bottom of the harbour when the raid ended, although two eventually returned to service, while other ships were damaged and fuel tanks ashore set on fire, while just two aircraft were shot down, with the crew of one of these being taken prisoner.

The Italians were forced to move their warships away from Taranto at first, although the next nearest port, Naples, was within reach of Malta-based Wellington bombers.

As the year ended, on 18 December, the Mediterranean Fleet was able to send two battleships, Warspite and Valiant, to bombard the port of Valona in Albania, being used by the Italians for their assault on Greece. Two days later, Cunningham visited Malta in Warspite, to a warm welcome. The Axis powers were soon to show, on 10 January 1941, that they were also capable of inflicting serious damage to the Royal Navy, when Malta’s vulnerability was also brought home with a vengeance. The convoy code-named Operation Excess was escorted towards Malta by Admiral Somerville’s Force H, and consisted of just four large merchantmen, three for Piraeus and one, carrying 4,000 tons of ammunition and 3,000 tons of seed potatoes, for Malta. Two other merchantmen, one with general supplies and another with fuel for Malta, came from Alexandria with the Mediterranean Fleet. Wellington bombers from Malta had raided Naples on the night of 8/9 January, damaging the battleship Guilio Cesare, and forcing her and the Vittorio Veneto to withdraw north to Genoa.

After initial skirmishes on 9 January, when Force H was bombed, Ark Royal’s Fulmars accounted for two bombers, but the real action came at the handover the following day. The Axis reconnaissance aircraft knew of the Mediterranean Fleet’s presence in the area, but the bombers failed to find them until 10 January. Both carriers kept their Fulmar fighters on constant readiness.

On 10 January, the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica attacked, with most of their bombs aimed at Illustrious. Luftwaffe Stukas quickly scored six direct hits and three near misses on Illustrious, whose deck was designed to take a direct hit of 500-lb bombs, but the hangar lifts were much weaker than this. The ship was forced to put in to Malta for repairs, where she remained prey to the attentions of the Luftwaffe and Regia Aeronautica until she was able to sail to the United States for repairs.

Matapan and the Fall of Greece

By this time, Cunningham had been confirmed in the rank of admiral, but he was to have little time to appreciate this vote of confidence by the Board of Admiralty. The Germans were preparing to attack Yugoslavia and Greece, and pressured their Italian allies to cut British seaborne communications between Alexandria and Athens. When Italian ships were sent into the waters south of Greece to attack British convoys, British aerial reconnaissance soon spotted the Italian ships. Cunningham intended to retain the element of surprise and considerable effort was put into making it seem that the Mediterranean Fleet was staying in port, convinced that Alexandria was awash with Axis spies. Then, under cover of darkness, the Mediterranean Fleet slipped out to sea late on 27 March.

The opening of the Battle of Cape Matapan started at daybreak the following morning when Formidable flew off aircraft for reconnaissance, fighter combat air patrol and anti-submarine patrols. They soon received two reports of cruisers and destroyers. In fact, Italian heavy cruisers were pursuing the British flight cruisers and in order to rescue them from this predicament, Formidable flew off six Fairey Albacores escorted by Fairey Fulmar fighters to attack the Italian ships, which were being joined by the battleship Vittorio Veneto.

While the Fulmar fighters shot down one of two Junkers Ju88 medium bombers that attempted to attack the Albacores, and drove the other one off, the six Albacores dived down through heavy AA fire to torpedo the Vittorio Veneto. No strikes were made, but they did force the Italian battleship to break off the pursuit of the British cruisers.

A second strike of three Albacores and two Swordfish, again with Fulmar fighters, was sent off while two Italian bombers attempted to attack Formidable. Vittorio Veneto’s AA defences were surprised by the Fulmars machine-gunning their positions and the bridge as the Albacores pressed home their torpedo attack. As the AA fire started to hit it, the leading aircraft dropped its torpedo 1,000 yards ahead of the ship. The torpedo struck home almost immediately after the plane crashed and the battleship was hit 15ft below the waterline, allowing a massive flood of water to gush in just above the port outer screw, so that within minutes the engines had stopped. Hard work by damage-control parties enabled the Vittorio Veneto to start again, using just her two starboard engines, but she could only manage 15 knots. A third air strike was then mounted by Formidable. When this arrived over the ship at dusk, they attacked the Italians, diving down through a dense smokescreen and then being dazzled by searchlights and the usual colourful Italian tracer barrage in an unsuccessful attack. Then an aircraft flying from Maleme in Crete spotted a heavy cruiser, the Pola, successfully torpedoing it and inflicting such severe damage that she lost speed and drifted out of position. Once the Italian admiral, Iachino, realized what had happened, he sent two other heavy cruisers, Zara and Fiume, with four destroyers to provide assistance.

Although the Italians were not expecting a night action, Cunningham knew that they were weak in night gunnery and intended to take advantage of this. By this time, the opposing fleets were off Cape Matapan, on modern atlases usually referred to as Cape Akra Tainaron, a promontory at the extreme southern end of the Pelopponese peninsula. At first, Cunningham thought that the Pola was Vittorio Veneto. As his ships prepared to open fire, the Italian rescue force of Zara and Fiume sped across Cunningham’s path and were illuminated by a searchlight from a destroyer. In the battle that followed, Zara and Fiume and two destroyers were sunk by the 15-in guns of the three battleships, while Pola was sunk in a torpedo attack from two destroyers.

The next morning, Cunningham had his ships pick up 900 Italian survivors before the threat of air attack stopped the rescue. Nevertheless, before leaving he relayed the position of the remaining survivors to Rome, saving many more lives. Although this was not the only time he did his best for a defeated enemy, he could seem harsh and unyielding to those around him. He considered that the naval airmen who attacked Taranto were only doing their duty, although he later admitted that he had not realized at the time what a ‘stroke it had been’. The effect on morale aboard Illustrious was bad, with angry sailors tearing down the notices announcing the awards which included nothing higher than a DSO. He maintained a small staff, which undoubtedly meant that there was less overlap and duplication, but it put them under pressure. Cunningham simply retorted that he had never known a staff officer die from overwork, and if he did, he could always get another one.

By 23 April, the Greek Army had surrendered and the Mediterranean Fleet found itself evacuating British forces to Crete. Had Crete been used simply as a staging post, all might have been well, but the mistake was made of attempting to defend the island, despite the shortage of aircraft and the fact that the British had left most of their heavy equipment and their communications behind in Greece. In both the evacuation of Greece and then of Crete, Cunningham prolonged the operation for longer than his orders required, saving many soldiers from PoW camps.

Leaving the Mediterranean

Cunningham left the Mediterranean in June 1942 and served in Washington as head of the British naval delegation until October. It was his turn to realize that he did not enjoy staff work and it was no doubt with considerable pleasure that he found himself as Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force for the North African landings in November 1942. Early the following year he was promoted to admiral of the fleet, and became C-in-C Mediterranean; as Eisenhower’s naval deputy he was responsible for the naval aspects of the landings in Sicily in July and at Salerno in September.

Meanwhile, the First Sea Lord at the Admiralty, the Royal Navy’s most senior officer, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound, had been increasingly unwell for some time. He was overworked and had to cope not only with the normal strains of running a major part of the armed forces, but the fact that the Admiralty was also an operational headquarters. When he resigned in September 1943, before dying in October, Cunningham was appointed as his successor. As the alliance with the United States grew ever closer, he also became a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff committees.

In his new role, Cunningham was quickly accepted by the other British service heads, and especially by the head of the Army, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Alan Brooke, later Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke. Cunningham is credited with the success of the Normandy landing in June 1944, and the formation of the new British Pacific Fleet, the largest and most balanced fleet the Royal Navy ever created and which operated under the overall command of Nimitz. Not for nothing has the official Royal Navy historian described Cunningham as standing ‘unique amongst the leaders of fleets and sailors’.

When the war ended, Cunningham was entitled to retire, but he resolved first to pilot the Navy through the transition to peace. There was a large reduction in the Defence Budget which proved to be a challenge for Cunningham, who later remarked in his memoirs: ‘We very soon came to realise how much easier it was to make war than to reorganise for peace.’ At the end of May 1946, Cunningham retired to Bishop’s Waltham in Hampshire. Ennobled, he attended the House of Lords irregularly but campaigned for justice for Admiral Dudley North, who had been relieved of his command of Gibraltar in 1940, and obtained a partial vindication in 1957. Cunningham died in London on 12 June 1963 and was buried at sea off Portsmouth.