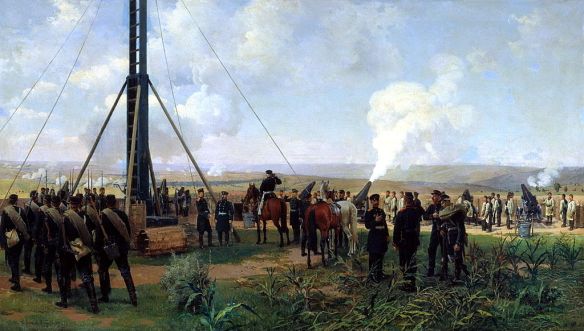

The artillery battle at Pleven. The battery of siege guns on the Grand Duke Mount, by Nikolai Dmitriev-Orenburgsky.

The Capture of the Grivitsa redoubt at Pleven, by Nikolai Dmitriev-Orenburgsky.

Date: July 19-December 10, 1877

Location: Pleven (Plevna) in northern Bulgaria

Opponents (* winner)

*Russians, Romanians, Bulgarians

Ottomans

Commanders

Russians, Romanians, Bulgarians: Grand Duke Nicholas; Prince Charles of Romania

Ottomans: Ghazi Osman Pasha

Approx. # Troops 150,000, including 120,000 Russians plus Romanians and Bulgarian volunteers

Ottomans: Probably more than 50,000

Importance

Regarded as the birthright of modern Bulgaria, the battle opens the way for the Russians to move south against Constantinople (Istanbul), but their stand here wins considerable sympathy in Western Europe for the Ottomans

In the early 1870s Ottoman power was in decline, but the empire still controlled most of the Balkan Peninsula. In the south Greece was independent, while to the north Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro enjoyed the status of autonomous principalities. In 1875 and 1876 uprisings occurred in Herzegovina, Bosnia, and Macedonia. Then in mid-1876 the Bulgarians also rose, only to be slaughtered by the Ottomans. Serbia and Montenegro then declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Russia, defeated in the Crimean War of 1854-1856 by a coalition that included the Ottomans, sought to recoup its prestige in the Balkans and secure a warm-water port on the Mediterranean. As a result, concerns mounted that fighting in the Balkans might lead to a general European war.

While the major European powers discussed intervention, the Ottomans, led by Ghazi Osman Pasha, were winning the war. By the autumn of 1876 it was clear that they would soon capture Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. That October Russia demanded an armistice, which the Ottomans accepted. A conference at Constantinople in December soon disbanded without tangible result, and in March 1877 Serbia made peace with the Ottoman Empire. Sentiment in Russia was then so strong for intervention that despite warnings of bankruptcy from his minister of finance, Czar Alexander II declared war on the Ottomans in April 1877, beginning the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878.

Because the Ottomans controlled the Black Sea with ironclad warships, a Russian land invasion proved necessary. In the last week of April 1877 two Russian armies invaded: one in Caucasia, advancing on Kars, Ardahan, and Erzurum, and the other in the Balkans. Romania was essential to a Russian drive down the eastern part of the Balkan Peninsula, and following agreement between Prince Charles of Romania and Alexander II, Russian troops crossed the Prut (Pruth) River into Moldavia. The Ottomans responded by shelling Romanian forts at the mouth of the Danube, whereupon on May 21 Romania declared both war on the Ottoman Empire and its independence. Serbia reentered the war in December. Bulgarian irregular forces fought with Russia, and Montenegro remained at war, as it had been since June 1876. Romanian support was vital to the Russian effort in terms of both geographical position and manpower in the ensuing campaign.

Russian forces under nominal command of Grand Duke Nicholas, brother of the czar, crossed the Danube River on June 26 and took Svistov (Stistova) and Nikopol (Nicopolis) on the river before advancing to Pleven (Plevna, Plevne), about 25 miles south of Nikopol. The Bulgarians acclaimed the Russians as liberators. Russian general Nikolai P. de Krudener, who had actual command, established his headquarters at Tirnovo and sent forces across the Balkan Mountains into Thrace, then back toward Shipka Pass through the mountains to defeat the Ottomans. Russian troops, assisted by Bulgarian partisans, also raided in the Maritza Valley, seemingly threatening Adrianopole.

The military situation changed when Sultan Abdul Aziz appointed two competent generals: Mehemed Ali, named Ottoman commander in Europe, and GhazI Osman Pasha. Mehemed Ali defeated the Russians in the south, driving them back to the Balkan Mountains with heavy losses. To the north the main Russian armies encountered a formidable obstacle in Ottoman forces sent to the Danube under Osman Pasha. Soon he had entrenched his men at Pleven. Ottoman engineers created in the rocky valley there a formidable fortress of earthworks with redoubts, trenches, and gun emplacements. The 10-mile Ottoman defensive perimeter was lightly held, with reserves in a secure central location from which they could rush to any threatened point.

Superior numbers led the Russians to underestimate their adversary. Failing to adequately reconnoiter the Ottoman positions, on July 19, 1877, the Russians assaulted the strongest portion of the line and, to their surprise, were repulsed with

3,000 casualties. The battle demonstrated the superiority of machine weapons in the defense, as the Ottomans were equipped with modern breech-loading rifles imported from the United States. They also had light mobile artillery. On July 30 Russian forces again attacked and again were repulsed.

Over the next six weeks Osman Pasha worked to improve his defenses, while the Russians demanded that Prince Charles of Romania furnish additional manpower. Charles agreed on the condition that he receive command of the joint Romanian-Russian force. Confident of victory, the allies then planned an attack from three sides with 110,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. On September 6, 150 Russian guns began a preparatory bombardment. The Ottoman earthworks suffered little damage, and there were relatively few personnel casualties. Wet weather also worked to the advantage of the defenders.

The infantry attack began on schedule on September 11. With Alexander II in attendance, at 1:00 p.m. the artillery fire ceased, and the infantry began their assault. The attackers took a number of Ottoman redoubts, and for several days it appeared that the allies would be victorious. But on the third day the Ottomans successfully counterattacked. The allies suffered 21,000 casualties for their efforts.

Russian war minister Dimitri Aleksevich Miliutin now recalled brilliant engineer General Franz Eduard Ivanovich Todleben, who had directed the defense of Sevastopol during the Crimean War. Todleben advised that Pleven be encircled and its garrison starved into submission. Osman Pasha, having twice defeated a force double his own in size, would have preferred a withdrawal while it was still possible, but the battle had captured the attention of Europe and created a positive image of Ottomans as heroic and tenacious fighters. Sultan Abdul Hamid therefore ordered him to hold out and promised to send a relief force.

The Russians committed 120,000 men and 5,000 guns to the siege. They also placed Todleben in charge of siege operations. Other Russian forces under General Ossip Gourko ravaged the countryside, preventing Ottoman supply columns from reaching Pleven from the south. The Russians also easily defeated and turned back the sultan’s poorly trained relief force.

Winter closed in, and the Ottoman defenders at Pleven, short of ammunition, were soon reduced to starvation. Osman Pasha knew that his only hope was a surprise breakout. On the night of December 9-10 the Ottomans threw bridges across the Vid River to the west and then advanced on the Russian outposts. The Ottomans carried the first Russian trenches, and the fighting was hand to hand. At this point, Osman Pasha was wounded and his horse shot from beneath him.

Rumors of Osman Pasha’s death led to panic among the Ottoman troops, who broke and fled. Osman Pasha surrendered Pleven and its 43,338 defenders on December 10. Although the Russians treated Osman Pasha well, thousands of Ottoman prisoners perished in the snows on their trek to captivity, and Bulgarians butchered many seriously wounded Ottoman prisoners left behind in military hospitals. Some 34,000 allied troops perished in the siege. With the Russians threatening Constantinople itself, in February 1878 the Ottomans sued for peace.

Russia imposed harsh terms in the Treaty of San Stefano on March 3, 1878, leaving the Ottoman Empire only a small strip of territory on the European side of the straits. Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro were enlarged, but the major territorial change was the creation of a new large autonomous Bulgaria, including most of Macedonia from the Aegean Sea to Albania. This would make Bulgaria the largest of the Balkan states, although the assumption was that it would be dominated by Russia. The Battle of Pleven is therefore regarded by Bulgarians as marking the birth of their nation. The treaty did not last, however. Britain and Austria-Hungary threatened war if the treaty was not revised, and Russia agreed to an international conference that met in Berlin in June and July 1878.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Berlin, Bulgaria was divided into three parts. Bulgaria proper (the northern section) became an autonomous principality subject to tribute to the sultan; eastern Rumelia, the southeastern part, received a measure of autonomy; and the rest of Bulgaria was restored to the sultan. Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro all became independent, and Greece received Thessaly. Russia received from Romania the small strip of Bessarabia lost in 1856 and territory around Batum, Ardahan, and Kars that it had conquered in the Caucasus, while Romania had to be content with part of the Dobrudja. Austria-Hungary secured the right to occupy and administer, though not annex, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The region continued to smolder, however. During 1912-1913 there were two Balkan wars, both of which threatened to become wider conflicts. Then in June 1914 the assassination of Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand led to a third Balkan war that this time became World War I. The military lesson of the siege of Pleven—that modern machine weapons gave superiority to the defense—was soon to be relearned.

References

Herbert, Frederick William von. The Defense of Plevna, 1877. Ankara, Turkey: Ministry of Culture, 1990.

Kinross, Lord [John Patrick]. The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. New York: William Morrow, 1977.

Sumner, B. H. Russia and the Balkans, 1870-1880. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1937.