Woodrow Wilson’s accession to the presidency in 1913 might have been expected to overturn the interventionist trend of the Roosevelt and Taft years. Though he had supported the war of 1898 and the annexation of the Philippines, Wilson had been critical of “gunboat diplomacy” and “dollar diplomacy,” often denouncing foreign economic exploitation of Latin America. His first secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, had been one of the leading opponents of American imperialism. And Senate Democrats had opposed the customs treaties with the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua.

Yet far from renouncing the interventionist policies of his Republican predecessors, Wilson expanded them. The stern Presbyterian professor believed that America had a duty to export democracy abroad, and he was prepared to act on it. “I am going to teach the South American republics to elect good men!” the new president confidently boomed to a startled British envoy, who later declared, “If some of the veteran diplomats could have heard us, they would have fallen in a faint.”

A great deal has been written about the differences between Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. It has even been suggested by Henry Kissinger, in his magisterial Diplomacy, that the two men were the yin and yang of American diplomacy, Roosevelt representing European-style Realpolitik and Wilson the voice of naïve American ideology. This is a misleading assessment. “Roosevelt,” concludes the foremost study of his diplomacy, “was prone by instinct to approach issues in terms of right and wrong and . . . he was just as much of a preacher as Woodrow Wilson.” Indeed when he was police commissioner of New York, Roosevelt had atop his desk a tablet inscribed with these words: “Aggressive fighting for the right is the noblest sport the world affords.” Roosevelt acted on this belief when he helped whoop America into a war to liberate the Cuban people from “murderous oppression,” and when he refused to support a pro-American president of Panama who had gained power through election fraud.

The difference between Roosevelt and Wilson was not primarily over ends but means. Wilson believed in the efficacy of international law and moral force. Roosevelt believed that American honor could be protected, and its ideals exported, only by military force. His famous slogan was “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” Wilson almost inverted this aphorism. The irony is that Wilson would wind up resorting to force more often than his famously bellicose predecessor had. This may not have been entirely accidental, for Roosevelt believed that his buildup of the military, and his well-advertised willingness to use it, deterred potential adversaries from challenging U.S. power. Wilson, by contrast, he condemned as one of those “prize jackasses” who combined “the unready hand with the unbridled tongue,” and hence made war more likely. This may be an overly harsh judgment—there was abundant personal animus between Roosevelt and his successor—but there is little doubt that Woodrow Wilson came into office little realizing how often and how much military force would be required to implement his ideals.

He would find out soon enough.

The first foreign crisis to confront the Wilson administration occurred in Mexico. Since 1876, America’s southern neighbor had been ruled by Porfirio Díaz, a dictator who had established a climate conducive to foreign investment and friendly relations with Washington. By 1910 Mexico was the site of more than a billion dollars in U.S. investment and home to more than 40,000 American expatriates. The 80-year-old Díaz was ousted in 1911, setting off a violent upheaval that would last a decade and permanently transform the face of Mexico.

Díaz’s initial successor was the idealistic and ineffectual Francisco I. Madero. In February 1913 Madero was overthrown and murdered by the ruthless General Victoriano Huerta. Woodrow Wilson, who took office just 10 days later, was so offended by the violent takeover of this “desperate brute” that he broke with longstanding tradition that held that a sovereign government would receive international recognition regardless of how it came to power. Wilson not only refused to recognize the Huerta regime, he lifted an arms embargo and allowed U.S. weapons to flow to Huerta’s opponents, the Constitutionalists led by Venustiano Carranza. Wilson made it the object of American policy to overthrow the dictator and extend self-government to the Mexican people.

The first open clash between the U.S. and the Hueristas occurred in Tampico, a foreign-dominated Gulf port that was a center of Mexico’s oil industry. On April 9, 1914, a party of nine American sailors in a whaleboat flying the U.S. colors was arrested by a Huerista shore patrol for being in a restricted military area without permission. As soon as the Mexican military governor found out, he ordered them released and apologized profusely for the mistake. But this was not good enough for Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo, the obdurate old cuss who commanded the local U.S. Navy squadron. Lacking a direct radio or telegraph link with Washington, he took the initiative, and in the navy’s nineteenth-century tradition (think of David Porter in Puerto Rico), demanded that the Hueristas fire a 21-gun salute to the Stars and Stripes in order to cleanse this stain upon American honor. The local Mexican commander balked at this imperious demand. Wilson, sensing a pretext that he could use to force a showdown with Huerta, made Mayo’s intemperate ultimatum his own. “The salute will be fired,” he grimly vowed, and ordered both the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets to steam toward Mexico. Huerta finally offered to stage a “reciprocal” salute—first a Mexican battery would salute the U.S. flag, then U.S. ships would salute the Mexican flag—but Wilson deemed this insufficient.

On Sunday, April 19, 1914, Wilson decided to break off a week of negotiations with Huerta, and at 3:00 P.M. the next day he appeared before a joint session of Congress to ask for a blank check to use armed force against Huerta. The House immediately approved the resolution Wilson wanted, but the Senate adjourned that night without voting.

At 2 A.M. on Tuesday, April 21, the president was awakened and informed that a German cargo ship, the Ypiranga, was heading toward Veracruz and would arrive later that morning with a load of munitions for the Hueristas. This would increase Huerta’s power and make him harder to dislodge. Wilson did not want to intercept a foreign ship on the high seas; in an odd bit of legal reasoning, he decided it would be better to seize the wharves where it was going to unload. This had the added advantage of denying Huerta customs revenues from Mexico’s largest port, which might help to dislodge the dictator. Later that morning, Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels sent a radiogram to Rear Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher, in command of the naval squadron off Veracruz: “Seize custom house. Do not permit war supplies to be delivered to Huerta government or to any other party.”

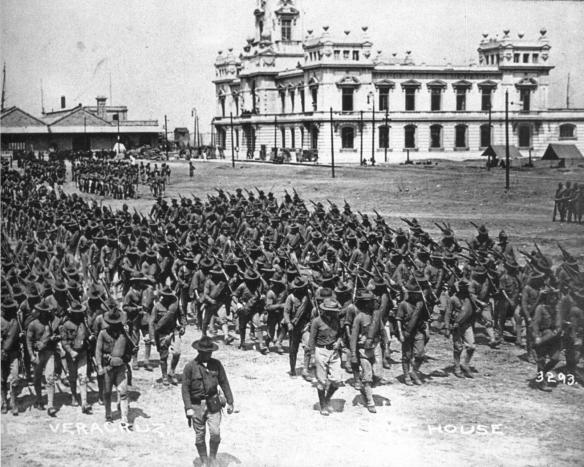

April 21 dawned gray and windy. With a storm brewing, Admiral Fletcher lost no time in executing his orders. Just after 11 A.M., whaleboats were hoisted over the side, and more than 700 marines and bluejackets plowed through the choppy surf toward Pier Four, Veracruz’s main wharf. A large and curious crowd of Mexican and American civilians assembled to watch the spectacle. The invaders, organized into a marine regiment and a seaman regiment, encountered no resistance as they clambered out of their boats, formed ranks, and began marching toward their objectives.

From a distance Veracruz looked beautiful, a picture postcard of beaches and pastel buildings surrounded by “indigo waters, sand hills, white walls and coconut palms, mountain peaks piercing the clouds, [and] an island scarred with the grim old fortress of San Juan de Uloa.” But upon closer examination the sailors and marines found the narrow cobblestone streets littered with garbage and rotting animal carcasses. Giant black vultures called zopilotes circled overhead and mongrel dogs ran wild. A powerful stench pervaded everything in this town of 40,000.

Wilson had counted on a peaceful occupation; he assumed that the Mexican people—“the submerged 85 per cent of the people of that Republic who are now struggling toward liberty”—would welcome American intervention to topple their dictator. This view turned out to be dangerously naive. Veracruz’s military commander, General Gustavo Maass, was determined to resist. He distributed arms to local militiamen and convicts from local prisons, and sent 100 of his soldiers to the waterfront with orders to “repel the invasion.” Just after they set out, he received orders from Mexico City to withdraw his force without a fight. Maass evacuated most of his 1,000 men, but by then it was too late to prevent a clash.

Just after noon on April 21, 1914, a shot rang out near the railway yard, a U.S. Navy signalman fell dead, and general firing erupted. The battle of Veracruz had begun. Mexican snipers took up positions on rooftops and in windows and began raining bullets down on the Americans. Americans began falling—by 2 P.M. four were dead, 20 wounded—and the sailors, unused to street fighting, bogged down.

Admiral Fletcher hoped to negotiate an armistice but he could find nobody to bargain with. A messenger discovered the mayor of Veracruz cowering in his bathroom, but the mayor said he had no authority over his armed countrymen. On the night of April 21, Fletcher decided that he had no choice but to expand his original mission from simply taking the waterfront to taking all of Veracruz. He was able to accomplish this goal the next day thanks to the arrival of 3,000 marine reinforcements, among them Major Smedley Butler.

“At daylight we marched right through Vera Cruz,” Butler remembered. “Mexicans in the houses, on the roofs, and in the streets peppered us from all directions. Some fired at us with machine guns. Since the Mexicans were using the houses as fortresses, the Marines rushed from house to house, knocking in the doors and searching for snipers.” Sailors trying to flush out the defenders had been mauled because they had simply walked straight down the middle of the street, but the marines employed sounder tactics. “Stationing a machine gunner at one end of the street as lookout, we advanced under cover, cutting our way through the adobe walls from one house to another with axes and picks,” Butler wrote. “We drove everybody from the houses and then climbed up on the flat roofs to wipe out the snipers.”

Although the navy also participated in this mission, the sailors proved less adroit at street fighting. A naval regiment led by Navy Captain E. A. Anderson, who had no experience in land warfare, advanced in parade-ground formation upon the Mexican Naval Academy, making his men easy targets for the cadets and other defenders barricaded inside the two-story building. The bluejackets’ advance was repulsed with casualties, the situation only being saved by three warships in the harbor that pounded the academy with their long guns for a few minutes, silencing all resistance. The bombardment killed 15 cadets, including José Azueta, the son of a commodore. He became a great Mexican martyr; a monument to him still stands in Veracruz.

By noon on Wednesday, April 22, 1914, the sailors and marines had complete control of Veracruz. In the process, the Americans suffered 22 killed and 70 wounded. The exact Mexican losses are unknown, but at least 126 died and 195 were wounded.

The Navy Department was so ecstatic about this victory that it gave away medals by the bushel. Congress for the first time authorized the Medal of Honor for naval and marine officers as well as enlisted men. Smedley Butler was awarded one of 55 Medals of Honor handed out for this minor two-day engagement, the most for any battle before or since. He was incensed at this “unutterably foul perversion of Our Country’s greatest gift,” and tried to return his decoration, but the Navy Department insisted he keep it. The irony is that Butler had deserved a Medal of Honor for his actions in the Boxer Uprising, but had never gotten one.

The army and navy brass assumed that the occupation of Veracruz would be a prelude to an advance on Mexico City, as called for in their war plans, and as had actually happened in 1847 during the last war with Mexico. Otherwise, the occupation made no strategic sense in their minds. They had not even drawn up any plans for a military intervention in Mexico short of all-out war. But President Wilson had lost his stomach for more bloodshed, and unlike his European counterparts in that fateful year, he refused to subordinate important political decisions to the demands of military timetables. He decided to head off a war with Mexico by not advancing beyond Veracruz. But he also did not want to relinquish the port, at least while Huerta was still in power. Army and navy officers were perplexed by what Admiral Mayo called a “decidedly strange . . . state of affairs,” under which the U.S. could occupy the principal port of a country it was not at war with. But the armed forces followed the commander-in-chief’s orders, even if they did not agree with them, and the U.S. Army moved in to administer Veracruz.

Chosen to command the port city was 49-year-old Brigadier General Frederick Funston. His career had languished since his daring capture of the Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo 13 years before. He had returned from the Philippines to San Francisco in January 1902 to recuperate from chronic ulcerative appendicitis. He immediately tried to cash in on his fame by going on a lecture tour, but before long a backlash against him set in. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge’s committee, investigating the conduct of the Philippine War, heard testimony that Funston had ordered prisoners to be tortured and sometimes shot. Funston did nothing to help his own cause. In one speech he declared that critics of the war ought to be strung up on the nearest lamppost. This caused such a furor that his old friend and admirer, President Theodore Roosevelt, sent word that he should shut up. This he did, but he got into more hot water with Secretary of War William Howard Taft in 1906, who ended his command of the Army of Cuban Pacification almost before it had begun.

Funston’s luck did not go permanently AWOL. When the 1906 earthquake struck San Francisco, Funston was deputy commander of the military district of Northern California. Since the commanding officer was out of town, Funston personally took charge of the relief effort. He once again became a hero, but was passed over for further promotion owing to the jealousy of older officers and concerns among his superiors about his temperament. Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels was hesitant to appoint “Fighting Fred” Funston as commander of the Veracruz occupation for fear that “he may do something that may precipitate a war.” This worry was reasonable enough but turned out to be unfounded. Funston was itching to proceed on to Mexico City—“Merely give the order and leave the rest to us,” he begged the secretary of war—but when no such order was forthcoming, he contented himself with running the port city.

Where possible, Funston tried to keep the original Mexican bureaucrats in place, but few of them would serve an army of occupation. Most of the jobs had to be filled by army officers. Their main task, as an American weekly newspaper noted, was fighting “not the Mexicans, but the enemies of the Mexicans and all mankind, the microbe.” Veracruz, which suffered from a polluted water supply and lack of adequate sewage, was swept regularly by epidemics of yellow fever, malaria, dysentery, smallpox, tuberculosis, and other diseases. Funston, following the example of the army in Cuba, the Philippines, and elsewhere, imposed sanitation at gunpoint. He even imported 2,500 garbage cans from the United States. As a result the death rate among city residents plummeted, and the vultures left town. In general the Americanos proved more efficient and honest than the Huerista officials they replaced; the police, for instance, no longer took bribes and actually cracked down on crime. It was, concludes one American historian, “a benevolent despotism, the best government the people of Veracruz ever had.”

The occupation quickly became a boring routine. The thousands of American soldiers had little to do. They marched hither and yon, and spent much time frequenting cantinas, bordellos and cinemas exhibiting new-fangled moving pictures. One of the few Americans to enjoy an adventure was an army captain named Douglas MacArthur, son of old General Arthur MacArthur of Philippine War fame. Assigned to Funston’s staff as an intelligence officer, Douglas decided to slip out of Veracruz with a few Mexican railroad workers to bring back some locomotives, which were in short supply in Veracruz. MacArthur returned with three locomotives—and an amazing tale of having shot it out with a party of Mexican cavalry that had attacked his little band. MacArthur was “incensed” that he did not win a Medal of Honor for this exploit.

Just 10 weeks after the occupation began, on July 15, 1914, the Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta resigned from office. The occupation of Veracruz—which denied him vital customs revenue—was undoubtedly a factor in his decision, but more important was the thrashing Venustiano Carranza’s rebel forces had administered to his army. Carranza replaced him as president, and although he refused to hold elections, Wilson nevertheless pledged on September 16 to withdraw U.S. forces from Veracruz. The actual pullout was delayed for a couple of months until Carranza agreed not to retaliate against civilians who had aided the occupation.

On November 23, 1914, all 7,000 U.S. troops in Veracruz unceremoniously marched down to the piers and boarded transport ships. By 2 P.M. they were gone, leaving behind copious stocks of arms for the Carrancistas, meticulous records of all administrative actions and not a few wailing girlfriends. Constitutionalist troops moved in, and before long the residents were once again tossing garbage into the streets.

What did this seven-month occupation accomplish? It did nothing to stop the delivery of arms to the Huerista regime. The Ypiranga simply diverted from Veracruz and offloaded its cargo south of the city on May 27, 1914; Wilson no longer cared. The occupation also did nothing to resolve the incident at Tampico that had started the whole affair. Admiral Mayo never did get his 21-gun salute. Instead he was forced to call on British and German warships to help evacuate all 2,600 American residents of Tampico because of anti-gringo rioting. The anti-American reaction was not limited to Mexico; the events of 1914 stirred up rioting across Latin America. An Argentine political cartoon summed up the prevailing Latin view when it depicted a menacing Uncle Sam demanding of a Mexican: “Salute my flag like it deserves or I’ll take off your hat with a cannon shot.”

For all these reasons the wife of the U.S. chargé d’affaires in Mexico City described the occupation of Veracruz as a “screaming farce.” But Wilson had reason to be satisfied anyway, for the occupation had contributed to the downfall of his nemesis, that “brute” Victoriano Huerta. Contrary to the expectations of America’s admirals and generals, a limited intervention in Mexico had more or less achieved its purpose.