After the Mexican War battle of Churubusco on August 20, 1847, Mexico’s General Santa Anna tricked U.S. General Scott into two unfavorable maneuvers. First, he agreed to declare a truce to establish peace negotiations, but this was a ruse. Even while Santa Anna sold supplies to the American invaders, he quietly reinforced his army to 18,000 men while the American force was down to 8,000 effectives.

The second trick was passing false intelligence to Gen. Scott. Santa Anna led Scott to believe that at Molino del Ray, the stronghold west of Mexico City and one mile west of the Hill of Chapultepec, housed a cannon foundry where they were melting brass church bells into heavy cannon. The Americans attacked Molino, and it turned into a costly victory where 750 Americans were killed, and every remaining wounded American was murdered by the Mexicans. After inspection, Scott discovered that there was no foundry there. The heavy losses at Molino brought the six companies of U.S. Marines into battle.

Mexico City was a formidable target. Surrounded by marshes and with approaches via eight causeways, Scott faced obstacles similar to those Cortez had experienced 329 years earlier. Since the southern approach to the capital was heavily fortified, the American plan was to attack from the west at the two garitos or gates to the city. Each garito bristled with cannon positioned to rake the roadway. Scott’s line then was Molino, then Chapultepec, then the two gates leading into the city. One causeway was the Garita de Belen, another headed north two miles to the Garita de San Cosme.

The Hill of Chapultepec, 200 feet above the surrounding plain, was 600 yards wide, surrounded by a ditch and a 12-foot wall, and topped by a palace that had been made into a military school. It was fortified into a makeshift fortress as the Americans advanced on the capital.

The castle had once been a resort of the Aztec princes. The hill was steep all around except for a slope on the west where the Marines decided to attack. It had a sand-bag barricade at the entryway, and the hillside was mined with charges that were fused to be set off from the fortress.

Generals Scott and Worth regarded the fortress as impregnable. Even though it was vulnerable to American bombardment, both officers were grim on the prospect, and Gen. Worth thought, “we shall be defeated.” The hill was a fearsome objective to assault—but if taken, the army would then be able to move onto the causeways leading into the capital.

Two storming parties of 250 men each were assembled. The Marines were assigned to the 4th Division commanded by Army Brigadier General John Quitman, a Mississippian. The Americans moved out of the tree cover and faced the mined hillside that led to the retaining wall of the castle terrace.

At 8 a.m. on Monday, September 13, the attack began. Quitman’s men attacked the southern side of Chapultepec. Captain Silas Casey led an assault party of 120 hand-picked soldiers and Marines under Marine Major Levi Twiggs, and 40 Marines commanded by Marine Captain John Reynolds. They faced 1,000 Mexican troops inside the fortress.

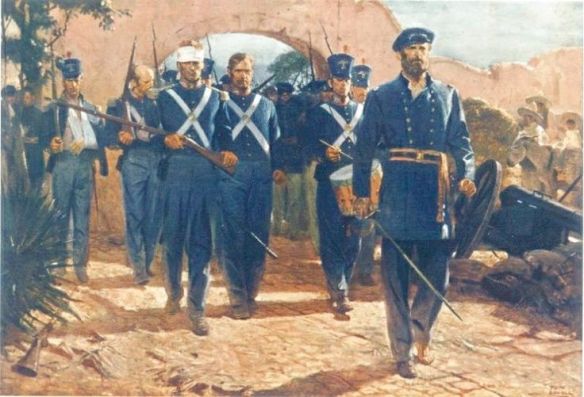

U.S. Marines storming Chapultepec castle under a large American flag.

The Halls of Montezuma

Chapultepec, also known as “the castle,” was an ancient Mexican shrine as well as a recent fortress. Three hundred years before the U.S. war, this had been the summer palace, replete with fountains, of Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor. In 1783, a Spanish viceroy built a new citadel on top of the ruins of the old palace. Surrounded by a huge retaining wall was a broad terrace that made for excellent cannon placement.

Around 1840, the Mexicans made this structure into their National Military Academy. Like at West Point, the young cadets learned military arts in their gray uniforms and tasseled blue caps. About one hundred of the cadets, though ordered to evacuate their school, stayed on and proudly fought to defend this memorial to Mexican history.

Six cadets became the boy heroes of Chapultepec. Those who died were: Vicente Suarez, age 13; Francisco Marquez, 14; Fernando Montes de Ora, 17; Agustin Melgar, 18; Juan de la Barrera, 20; and Juan Escutia, 20.

Cadet Escutia reportedly took the Academy flag from its staff, wrapped it around his body, and valiantly plunged to his death on the rocks below the castle rather than see the flag surrendered to the Americans.

Two of Chapultepec’s guns were soon disabled by American battery fire, and the disheartened Mexican soldiers began to desert. From the terrace came a murderous rain of grapeshot and musketry. General Pillow was struck in the ankle, but the whole American force flowed over the redoubt. The Americans were able to cut the canvas powder line that led to the mines and none exploded.

The Marines struggled up the steep southern side, fighting hand-to-hand with bayonets and clubbed rifles. Corporal Hugh Graham and five Marines were killed.

Casey and Twiggs fell wounded, the latter fatally, and they stopped 200 yards short of the guns. Scaling ladders finally reached the Americans. They bridged the ditch and their first wave was mowed down by the Mexicans. So many ladders rose, seemingly at once, that 50 men were up abreast. “And with a shout of victory, the great body of troops rushed over” the walls and gained the castle.

The Americans turned the Mexican guns around, relieving the pressure on Quitman’s column. The Mexicans fell back and the Americans charged the castle’s main gates. The Mexicans fled so hastily that they “jumped down the eastern side of the rock, regardless of the height.”

The young cadets who had refused to desert the school fought to the end. The six boys were killed, as an American correspondent put it, “fighting like demons.” They were to be called Los Ninos Heroicos—the heroic children.

Mexican officers watching their defeat from a distance said, “God is a Yankee,” as Americans from both sides reached the castle. At 9:30 a.m., an American flag was raised over the fortress.

Marine Captain George Terrett led First Lieutenant John Simms, Second Lieutenant Charles Henderson (son of the Commandant), and 36 men to skirt the heights and pursue the retreating enemy northeasterly towards the city itself. Terrett and his Marines raced up the road under heavy fire. Twenty infantry, led by Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant, the future General and American President, joined them as they fought their way up the San Cosme causeway. They were the spearhead of the army contingent.

Casualties were severe until the Americans remembered the tactic they used at Monterey—breaking their way through the walls of buildings and hauling their guns through them. This tactic also enabled them to fire from the roofs.

General Worth’s bugles sounded recall. Terrett went back to report, but Simms and Henderson attacked with 85 men. The gate was too heavily defended to rely on a frontal assault alone, so Marine Lieutenants Simms and Jabez Rich led seven marines to attack from the left. Four were hit. Henderson, wounded in the leg, attacked from the front. Two more men were hit, but together, the two groups seized San Cosme gate as darkness fell.

Worth again sounded recall and the Marines and soldiers withdrew. Six Marines had been killed. Once Chapultepec fell, Quitman moved his division under fire east on the Belen causeway with the Marine battalion right behind a South Carolina regiment. At the Belen gate, they were stopped by enemy fire and Marine Private Tom Kelly was killed. Finally, at 1:20 p.m., the Marines and infantry carried the gate. At dawn on the 14th, Quitman and Worth prepared to assault the city through the two entrances—but Santa Anna had already pulled out.

Though Scott was angry at Quitman for the costliness of his attack on Belen, he felt the Mississippian and his Marines had earned the honor of formally taking the city. Within hours, he would appoint Quitman Mexico City’s military governor.

The Americans hardly looked the part of a conquering army. The victorious General Quitman wore only one shoe as he marched at the head of his ragged, blood-stained troops. Only about six thousand Americans remained on their feet—little more than half of those who had left Puebla.

Quitman’s men walked through the crowded streets into the Grand Plaza and took the National Plaza, where before had stood the halls of Montezuma. The Marines were stationed to guard the Palace. The U.S. Marines were now patrolling the halls of Montezuma. In the spring, the veterans were joined by a new 2nd Marine battalion of 367 men commanded by Major John Harris.

On February 2, 1848, the Mexicans accepted peace as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. Even though the U.S. was victorious, they agreed to pay Mexico 15 million dollars in cash for the land they coveted. Mexico had lost half her territory—an area larger than France and Germany combined. The American boundary with Mexico would run from the Gulf of Mexico, up the Rio Grande, to the New Mexican border. Then it would continue west to the Pacific at a point one league, or three miles, south of San Diego.

The outspoken Duke of Wellington called Gen. Scott “the greatest living soldier.” It had been Scott’s flexibility and imagination, his attention to reconnaissance, and his tendency to strike from an unexpected side that supplied the tactics that won the war. In addition, he had the support of solid officers like Thomas (later Stonewall) Jackson, Robert E. Lee, U.S. Grant, P.T. Beauregard and Jefferson Davis. Only 13 years later, all of these men would become major players in the American Civil War.

With this victory, the expansion of the continental United States from coast to coast was now complete. And, in addition to Mexico, the Marines had also captured the opening words to their future Marine Hymn.