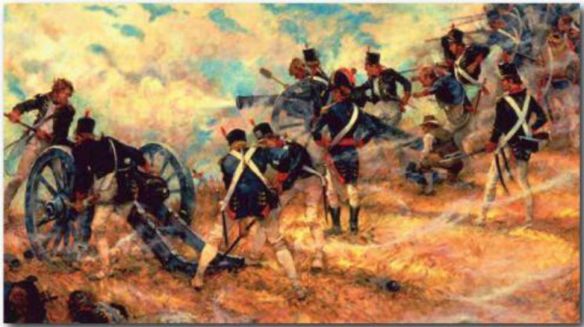

The Final Stand at Bladensburg Artist: Colonel Charles H. Waterhouse, USMCR

The defense of Washington was a shameful affair. It was the most serious defeat of American arms ever experienced. The army had broken and fled, but Barney’s men and Marines, even though overrun, had held their ground to heroic glory. The Marines had eight killed and 14 wounded. Miller and Sevier were brevetted majors. The Americans lost 26 killed and 51 wounded. The British attackers lost 500 killed and wounded.

By June of 1814, the British had been blockading the American coast for 18 months. With 4,000 regulars, Royal Marines, and negroes bribed with promises of freedom, they were also poised to invade Washington. The British commander, Vice Admiral Cochrane, was being urged by Sir George Prevost, Governor General of Canada, to burn the city in retaliation for the Americans’ burning of Canadian Parliament buildings in York and for the burning of Newark.

The Navy ordered Commandant Wharton to raise a battalion of Marines to help protect the Chesapeake Bay from incursion; President Madison assigned Brigadier General Winder to lead a composite force of infantry, state militia and volunteer riflemen to defend Washington and; Commandant Joshua Barney, a tough, 54-year-old Revolutionary War veteran was assigned to the naval defense.

In June, Barney found himself still blockaded after a number of skirmishes with the 21-ship British fleet up the Patuxent River. The Marines under Captain Sam Miller had cooperated with Barney, supplying artillery fire from the shore, but he was unable to break through.

The British entered the Patuxent River on August 17, and two days later landed unopposed at Benedict, Maryland. Barney, outflanked and outmaneuvered by 40 British barges, had blown up his flotilla of 13 gun barges. The British started their 40-mile march to Washington.

Barney and his flotilla men joined Winder’s men. Capt. Miller, with 110 Marines from the Washington Navy Yard, along with five artillery pieces, also joined them. The Marines now had two 18-pounders and three 12-pounders.

On Wednesday the 24th, the British approached Bladensburg four miles northeast of Washington at a bridge that crossed the eastern Potomac. Earlier, Gen. Winder had thought the British would attack Washington from the east in combination with their fleet passing Fort Washington south of the city.

Winder marched out of Washington and ordered Barney—much to Barney’s disgust—to stay behind and guard the Eastern Branch Bridge (now the Sousa Bridge). At the bridge, Barney was able to personally complain to President Madison and had his orders changed. This was the only American battle where the President and his cabinet—the Attorney General, the Secretary of War, and Secretary of State—were all on the battlefield. The bridge was blown and Barney, his sailors, and Marines with their artillery, marched to the battle.

With the temperature at 100 degrees, the Americans were drawn up in three lines on the Washington side of the Potomac. The first line to encounter the advancing British were riflemen under Major Pinkney and two companies of militia under Captains Ducher and Gorsuch, and Captains Myers and Richard Magruder with 100 artillerymen and six 6-pounders from Baltimore.

The second line was composed of Bruch’s artillery and Sterett’s 1,350 men from the 5th Baltimore Volunteer Regiment under Lieutenant Colonels Ragan and Schutz.

The 3rd line—the heaviest—was made up of 1,200 men from a regiment of Maryland militia under Colonel Beall and 300 district militia from the 12th, 36th and 38th under Colonel Magruder (not to be confused with the junior officer, Captain Magruder from Baltimore). The center was held by Barney’s flotilla men and the Marines’ battery along with Scott and Peter’s battery. Brent, with the 2nd Regt. of Smith’s brigade and Waring’s battalion of Maryland militia, were posted behind Peter’s battery. A total of 7,000 men and 26 cannon were set to receive the British attack but of these, only 900 were enlisted men; the rest were untried militia.

Barney positioned his 500 flotilla men in the center, on a rise commanding the bridge and the road along which the British would come. On his right were 114 Marines and 370 sailors, all serving as infantry. Barney commanded the guns and Marine Captains Miller and Alex Sevier supervised the infantry.

The British crossed the bridge under heavy American fire and then retreated. They attacked again and took heavy casualties from American cannon. The American riflemen with their Pennsylvania rifles poured a deadly fire—but the British were continually being reinforced by more brigades joining the fray.

The Americans fell back to the 2nd line. The Yankees charged with the bayonet and once again pushed the British back. Then another British brigade came on line, turned the American left flank and started their rocket attack on the untrained militia. Ragan and Schutz’ men were frightened by the rockets and fled. The 2nd line collapsed and now the British took on the 3rd line.

Barney’s fire had a terrible effect on the redcoats. When the British moved to hit their right flank, they met Miller’s Marine fire from the 12-pounders. The U.S. Marines were well trained in handling the great guns and wreaked havoc upon the enemy. The British were cut up, losing several officers including Colonel Thorton, who was severely wounded, and General Ross, who had his horse shot from under him. The Marines were obstinate and maintained their position against fearful odds.

Because they were heavily outnumbered, the Americans charged Navy-style. With the shout, “Repel boarders,” the Marines attacked with bayonets and the Navy with cutlasses. The charge broke two British regiments, but the British light infantry took both of the Marines’ flanks, wounding Barney severely and killing his horse. Miller was down, badly wounded in the arm and out of action. The British flanked wide, forded the river, cut through the militia and overran the Americans. The American militia had failed to stand their ground because of a rumor launched by the British that the negroes had risen up on the day of the battle to fight for their freedom—the additional worry that their homes and families were in danger being more than they could bear. The Navy flotilla men stood their ground, retired in order, and left their dead and wounded. Both Barney and Miller were captured. The battle was over in four hours, and Gen. Winder was forced to order a general retreat.

The American lines with their troop dispositions would almost certainly have been competent to roll back the invasion except for the interference of the President and his cabinet. James Monroe, the Secretary of State, was credited with the American defeat after he moved the 2nd line a quarter-mile to the rear against Gen. Winder’s wishes. This movement caused the 1st line to be unsupported, and exposed the 2nd line to rocket fire. This fickle civilian interference with Army decisions was seen again in Vietnam 152 years later.

The defense of Washington was a shameful affair. It was the most serious defeat of American arms ever experienced. The army had broken and fled, but Barney’s men and Marines, even though overrun, had held their ground to heroic glory. The Marines had eight killed and 14 wounded. Miller and Sevier were brevetted majors. The Americans lost 26 killed and 51 wounded. The British attackers lost 500 killed and wounded.

Word got out to the Washington city inhabitants that “the British were coming,” and 8,500 citizens began a sudden and confused exodus. The government, the Army, and even the Commandant of the Marine Corps fled the city. The national records and Army records were put in linen bags and taken to Leesburg, Virginia. Commandant Wharton took Captain Crabb and the Marine Barracks guard to Frederick, Maryland. The Marines guarded the paymaster whose flight from Washington scandalized the Corps.

That evening, the British marched six miles into Washington. Reduced to a pillaging party of 200 torch bearers, they entered the city of 900 buildings like barbarians. Admiral Sir George Cochrane delighted in torching cities and thirsted for plunder but thought Washington would pay a ransom to save the city from destruction. Ross sent an agent to discuss the ransom, but no one was there to negotiate with him. So the torches were lit.

The British burned some private buildings: The National Intelligencer, an anti-British newspaper; a rope-walk; and a tavern among them. Any house that fired a shot at the column was destroyed, just as had been done by Napoleon in Moscow. Ross’ horse was killed in one such attack. After two nights in Washington, the British burned most of the public buildings: the unfinished Capitol, the Library of Congress, the Treasury buildings, the Arsenal, the barracks for 3,000 troops, and the President’s house. The White House got its title later when the blackened building was whitewashed to cover up the scorch marks. In all, a total of two million dollars worth of property had been destroyed. Only the Patent Office was spared. Also burned were national shipping stores and buildings at the Navy Yard totaling one million dollars.

The British enacted martial law over the Washingtonians who had to remain indoors from sunset to sunrise under pain of death. At the Navy Yard, the Americans hid a quantity of powder and shot in a well. One British soldier peeking in the well with a match blew the place up, along with an adjacent powder magazine, killing 12 British and wounding 30. The light of the fired city was seen 40 miles away in Baltimore.

Supposedly, the Marine Barracks at Eighth and I Street was spared by the British because of the heroic U.S. Marine stand at Bladensburg, though some historians dispute this account.

The British would have burned more of the city save for a tornado and lightning storm that actually killed British soldiers and drove them off to their ships. Many believed this was divine intervention. It did seem as though God wanted democracy to prevail.

Houses were unroofed and the enemy left they way they had come, through Bladensburg. They left their dead on the battlefield and gave 90 of their wounded to Barney’s men for care. They embarked at Benedict and three days later attacked Alexandria, Virginia.

The British had no intention of holding Washington. Their reason for staying in the U.S. was to invade Louisiana and take possession of the Mississippi valley. England and Spain both intensely disapproved of the Louisiana Purchase by the U.S. From Napoleon—so when the British attacked New Orleans, a cadre of civil servants came along with the British army to rule over the coveted territory.

The Battle of Bladensburg left little to celebrate—but Dolly Madison, the First Lady, did manage to save some of America’s national treasures, most notably George Washington’s famous portrait. The heroic stand of the Marines and Navy had allowed precious time for the removal of American documents to safety, including the Declaration of Independence.