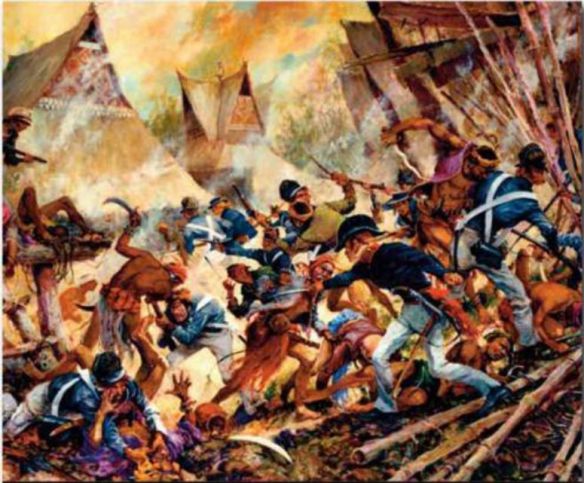

Quallah Battoo Artist: Colonel Charles H. Waterhouse, USMCR

Less than ten degrees north of the equator, on the island of Sumatra, lies the rich pepper-growing region of Acheh. Beginning in the 1790s, New England trading ships would stop along the island’s western coast to exchange Spanish silver for the spice, needed not only to flavor and preserve food, but for the lucrative trans-Atlantic trade with Europe.

American ships, based primarily in Salem, had made nearly a thousand voyages carrying away 370 million pounds of pepper worth 17 million dollars at wholesale—almost half the pepper produced in Acheh during this period. A pound of pepper then sold for $13.

The American ships were faster, and the Dutch and British disliked their competition in this lucrative business. They pressured the Sultan of Acheh, Muhammed Shaw, to detain American ships in violation of trading laws. The British went so far as to try to entirely exclude American trade from Acheh. It is unclear how much of the piracy on American ships was pure robbery and how much was influenced by the colonial power games of the period.

In January 1831, one of these American merchant vessels—the Friendship—dropped anchor off the Sumatran town of Quallah Battoo to take on a load of pepper. A band of Malay pirates in three proas, or ships, boarded the Friendship, murdered a large part of the crew, looted the cargo and drove the craft ashore. Their plunder included four chests of opium which was used in medicine, and 18,000 Spanish dollars.

The Malay pirate fleets along the Straits of Malaka were considered the “Vikings of the East.” Their proas were 50 feet long, fast, and nimble, using both oars and light sails, and were armed with swivel guns mounted on bulkheads. The pirates, dressed in scarlet and chain-mail, brandished krises—a sword with a wavy blade—two-handed swords, and flintlocks. They were famous for either murdering every soul on board, or selling the few survivors to slavery.

The Captain of the Friendship, Charles Endicott, had been ashore during the attack. When he made a complaint to the local chieftain, Mahomet, insult was added to injury for Mahomet then put a price on the head of both the Captain and his officers. With the help of a friendly native chief, Po Adam, Endicott enlisted the help of three other merchant captains who agreed to help him recover his vessel. Although the ship was recaptured and returned, her owners sent a vigorous protest to President Andrew Jackson demanding retribution.

President Jackson declared that “a daring outrage” had been committed on the seas of the East Indies involving the “plunder” of one of its merchantmen engaged in the pepper trade at a port in Sumatra. There appeared to be no room for diplomatic action, as Jackson believed that “the piratical perpetrators belonged to tribes in such a state of society that the usual course of proceedings between civilized nations cannot be pursued. I forthwith dispatched a frigate with orders to require immediate satisfaction for the injury and indemnity to the sufferers.”

At New York, the frigate Potomac, equipped with forty-two 32-pounder cannon, was rigged and ready to sail for the punitive expedition. The frigate had orders to “inflict chastisement” and carried a detachment of Marines and three detachments of seamen under Commodore Downes to punish the natives for their treachery.

Originally under orders to proceed to China via Cape Horn and the Pacific, the Potomac’s route was changed to the Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean as a result of the protest by the Friendship’s owners and the outcry from the general public. On Feb. 5, after sailing for five months, the Potomac, disguised as a Danish East Indiaman, anchored five miles off Quallah Battoo.

At 2 a.m. the next day, 282 Marines and sailors embarked on the ship’s boats and hit the beach for the attack. Divided into groups, the men were assigned to each of the four forts guarding the town. At dawn, the column led by Marine Lieutenants Alvin Edson and George Terrett moved forward. The Marines heading for Tuko de Lima nestled in the jungle behind the town.

Within minutes of the Marine approach, the Malays were alerted and the fighting became intense. The enemy met the Marines with cannon, muskets and blunderbusses (early shotguns). Charging forward, the Marines’ “superior discipline and ardor seemed fully to compensate for their want of numbers.” They broke through the outer walls, blew up the stockade gate, and captured the fort. Edson, with a small guard, pushed through the town to join in the attack on the remaining fort.

As smoke from the other forts drifted overhead, Edson, his Marines, and a detachment of sailors smashed through the bamboo walls of Duramond’s fort and engaged the kris-wielding Malays. Dressed in full blue uniform, Lt. Edson parried the lunge of a defender with his Mameluke sword while a Marine at his side parried with his bayonet. In this hand-to-hand combat with the Marines, the Malays fought to the death. Within minutes, the fort was taken, with only a few Malays left to flee into the jungle.

With the forts dismantled, the town ablaze, a few Malays hiding in the jungle, and the surf rising, the Marines and sailors were recalled. Over 150 Malay pirates, including Mahomet, were killed, with the Americans suffering just one sailor and two Marines killed and 11 wounded.

This successful attack would deter the Malays and others from similar aggressions for quite some time. In addition to their skill with cold steel, the Americans had emerged victorious due to their long-range, light-caliber cannon and their ability to deliver rapid rifle fire.

Under cover of a Marine guard, the boats embarked for the Potomac. Later in the day, all hands gathered on deck to witness the burial of their three shipmates killed in the attack.

Other rajas from nearby states sent delegations to the ship pleading that Downes spare them from the same fate they had suffered at Quallah Battoo. Downes informed them that if any American ships were attacked again, the same treatment would be given to the perpetrators.

The next morning, the Potomac moved within a mile of Quallah Battoo, ran out her long 32-pounder cannon and bombarded the town, killing another 300 natives before raising sail and heading for sea. This was the first-ever official U.S. military intervention in Asia. This was the second time—after Tripoli—that the Marines had been called in to protect American business and retaliate for the murder of American citizens.

It is interesting to note that 180 years later, American forces are once again engaged in similar situations with modern-day pirates off the coast of Somalia.