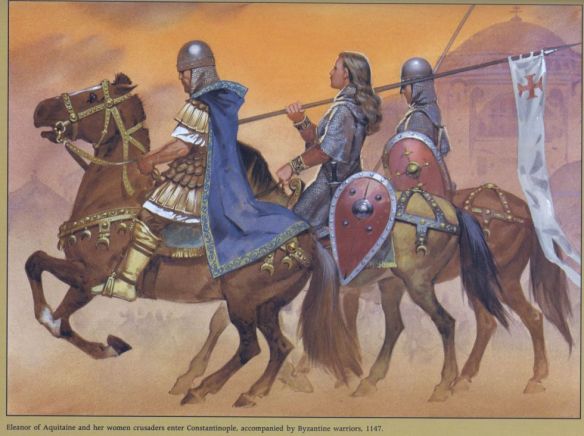

Eleanor of Aquitaine: (A.D. 1122?–1204) Romancers have placed her in the Second Crusade, clad in polished armor, plume dancing in the sun, dashing over the hillsides and killing Moors. The reality is hardly less impressive. On Easter Day, A.D. 1146, she offered the Abbé Bernard of Clairvaux, at Vézelay, her thousands of vassals, who formed the core of the Second Crusade. She intended to lead her legion personally and opinions vary as to how far she actually succeeded, although contemporary legend assumes the most. On the day of her army’s departure, Eleanor appeared in Vezelay riding a white horse, clad in armor, “with gilded buskins on her feet and plumes in her hair,” surrounded by other armored women, including Sybelle, Countess of Flanders, Mamille of Roucy, Florine of Bourgogne, Torqueri of Bouilon, and Faydide of Toulouse, all splendidly appointed. If it was a charade, she kept it up all along the route to the Holy Land. She met the Byzantine Emperor Manuel Komnenos and went from his court, by sea, to Syria, where her uncle, Raymond of Poitiers, one of the most brilliant knights of the age, was ruler. She went thence to Jerusalem, where she was greeted by Queen Melisande, ruler of Christians during the Crusades. Melisande not only fought Moslems, but also her own son, refusing to give up her rule when he came of age.

Independent evidence from the Greek historian Nicetas describes European women in the Crusades, and names especially “the Lady of the Golden Boot,” whom we can reasonably assume to be the same Eleanor with gilded buskins who started out from Vézelay, though some historians believe Nicetas referred to a troop of women in the employ of the German Conrad. The Greek historian describes her elegant and martial bearing, and describes, as well, her armored ladies with spears and axes, mounted on fine chargers.

Eleanor had been inspired by Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered and the character of Clorinda when she had armor specially made for herself and her ladies-in-waiting. Many historians today dismiss this event, and suggest that, at the first sign of trouble, she and her women turned around and headed home. Nicetas’ report strongly suggests otherwise. The Bull of the Third Crusade (1189) expressly forbade women to join the expeditions, although the First Crusade included equal numbers of men, women, and children, and the Second seems to have included numerous noblewomen inspired by Queen Eleanor after her spectacle at Vézelay, where she had ridden about the countryside calling for crusaders. Whether the Bull of the Third Crusade was obeyed seems unlikely, as too many of the warrior-monks were of denominations that included nun auxiliaries, and a great many mendicant-nuns were free to roam at will.

#

Medieval nuns were often members of wandering sects and traveled armed for self-defensive reasons. Others were adjunct to famous sects of fighting monks and accompanied them on the Crusades. Still others learned to fight for the protection of their lands and convents in a tumultuous age, as was the case with Philothéy Benizélos of Greece and Julienne du Guesdin of Brittainy. At the siege of Seville by Espartero, an anticleric, the nuns of Seville rose against him, so that his siege was repelled. There can be no question but that nuns and abbesses have had a great propensity for violence, as witness the stories of Chrodielde and Leubevére warring in the sixth century for control of an abbey, or Renée de Bourbon in the late 1400s in armed struggle for reforms. In the monk wars of early Christian Ireland, women were reported fighting amidst the clergy, undoubtedly nuns.

An eleventh-century nun’s marginalia in an illuminated manuscript shows a nun jousting with a monk on horseback and defeating him. This piece can be seen reproduced in Karen Peterson and J. J. Wilson’s Women Artists (1976). Some would say the artist was being satiric, but the reality of her age better upholds the conclusion that she was depicting actual military exercises practiced by monks and nuns. The ill-fated First Crusade led by Peter the Hermit was most assuredly made up of men, women, and children. Misson in Voyage d’Italie (1688) reported his personal inspection of an arsenal of the Palazzo-Real, which included cuirasses and helmets for women, which he was told were worn by Genoese ladies who fought Turks in 1301. Searching for confirmation, he uncovered three letters in the archives of Genoa, written by Pope Boniface VIII, discussing in detail the “warlike infatuation” of Genoese ladies who were Crusaders in 1383. As they are referred to as “ladies” rather than courtesans, and known to the pope, it is probable that they took vows before leaving for the East, in the manner of the monk-knights. If these women had not taken such vows, their troop would almost certainly have been referred to in a manner similar to that of the twelve hundred women-at-arms accompanying the duke of Alva in Flanders in the late 1500s, who were considered harlots for not taking vows.

An account survives, written by the sister of a monk (perhaps “sister” is not literal but a reference to her status as a nun), describing her experience during Saladin’s siege of Jerusalem: “I wore a helmet or at any rate walked on the ramparts wearing on my head a metal dish which did as well as a helmet. Woman though I was I had the appearance of a warrior. I slung stones at the enemy. I concealed my fears. It was hot and there was never a moment’s rest. Once a catapulted stone fell near me and I was injured by the fragments.”

Crusading women were romanticized in literature, plays, and songs, so that even Eleanor of Aquitaine was inspired to a women’s crusade and had armor made for her ladies-in-waiting. Among the queens of Europe whose valor in the Crusades is certain, we must count Florine of Denmark, Marguerite de Provence and Berengaria of Navarre. Additional indicators include the “troop of Amazons” that accompanied Emperor Conrad to Syria, and the women Crusaders in the ranks of William, Count of Poitiers, as reported by Guibert de Nogent in Gesta Dei per Francos (God’s Deeds of the Franks), book VII.

Of later periods, there are clear records regarding the unconventional activity of nuns. Le Lusca in Introduzione al Nouvellare was amused by the women of the Alpine convents who on certain days “were permitted to dress up as gentlemen, with velvet caps on their heads, tight-fitting hose, and having sword at side,” and come out of holy seclusion to partake, as gallants, in carnival society. Antonio Francesco Grazzini reports also of nuns who arrived at carnivals clad as cavaliers, swords at side, acting as gallants. Until reforms started by the Council of Trent, Italian convents were places of considerable liberty, with young patricians sporting in the gardens with the nuns, or, even more notoriously, the nuns “converting” maidens and widows by spending nights in their beds and taking them afterward to their convents. Novelists may seem to have exaggerated these propensities, yet the records show that in 1329 the nuns of Montefalco were excommunicated for such behavior; in 1447, several nuns were “reformed” by means of life imprisonment; and, in 1472, a Franciscan commissioner reported on the “irreligious and unbridled lives” of nuns. A 1403 law prohibited citizens of Bologna from any longer hanging about the convents or to converse and play music with the nuns.

Le President de Brosses, in Lettres familière écrites d’Italie, volume 1, was equally amused by Italian nuns, who as a rule carried stilettoes. These Lettres include an account of the abbess of Pomponne who fought a duel with a lady who wished to take over the abbey. Various popes found it necessary to declare the heretical nature of fighting women, in an attempt to minimize their participation. The centuries-old ban on women wearing armor would be the technicality upon which Joan of Arc was condemned to burn.

#

Florine: Betrothed to the king of Denmark, she accompanied him in A.D. 1097 on the ill-fated First Crusade, and died with him in battle.

Marguerite de Provence, Queen of France: (A.D. 1221–1295) Daughter of Raymond Berenger, she married Louis IX in 1254. She accompanied him on the Crusade and was in Damietta with him during a siege. At the height of the battle, she elicited a vow from an officer to behead her if the Moslems breached the walls. She behaved “with heroic entrepidity” when the king was captured.

There were many such women of the Crusades. They were “animated by the double enthusiasm of religion and valor,” and they “often performed the most incredible exploits on the field of battle, and died with arms in their hands at the side of their lovers.”

Berengaria of Navarre: (A.D. 1172?–1230?) Daughter of Sancho the Wise, King of Naples. She married Richard the Lionheart in 1191 and accompanied him to the Mideast, participating in the Crusade against Saladin. After the death of Richard, she founded an abbey and ruled its vast estates.

Chrodielde: A martial nun of the convent of Poitiers. Her bid to usurp Leubevére, abbess of Cheribert, in A.D. 590, began with political maneuvering and escalated to battle. Repulsed from the convent along with her partisans, Chrodielde withdrew to the fortified cathedral of St. Hilary and there raised an army of criminals and outcasts, who fought against the bishops seeking Chrodielde’s arrest. At the heart of Chrodielde’s popularity with the peasants was the greed of the landholding church authority, who were frankly no better than any other landlords then or now. It seems evident that nuns and midwives commonly filled the void of sympathetic leadership among the peasants of the medieval world, which is but one of the reasons for the massive witch burnings.

Childebert, King of France, sent his troops to put down the war between Chrodielde and Leubevére, “but Chrodielde and her banditti made such a valiant resistance that it was with difficulty the king’s orders were executed.” Chrodielde was ultimately excommunicated for leading peasants to rebellion.

Leubevére: Falsely accused of impious crimes by Chrodielde, Leubevére, abbess of St. Radegunde convent, repulsed her rival and afterward waged war against Chrodielde’s army of thieves, outcasts, and disenfranchised peasants. The convents and monasteries of A.D. 590 tended to be little more than the estates of wealthy landholders with forces to defend their rights and to manage troublesome serfs. The bishops called upon the king of France to quell these warrior-nuns. King Childebert sent forces that were hard put to suppress Chrodielde. Leubevére was later found innocent of Chrodielde’s charges, but was nonetheless dragged in the streets by her hair, then imprisoned, for leading nuns to battle.