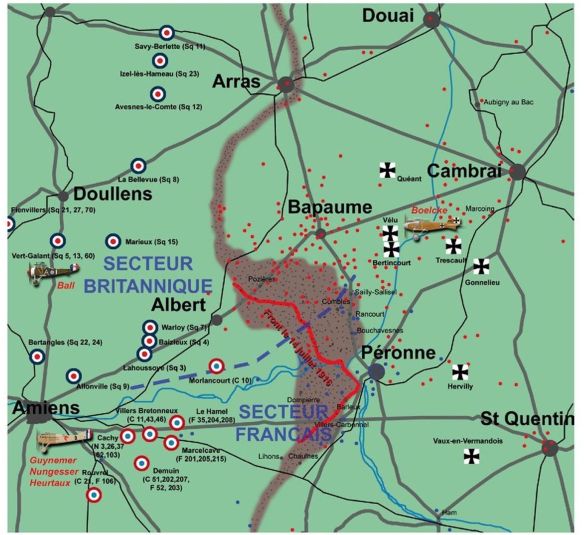

The land battles on the Somme between July and November 1916 had a direct effect on the concurrent air operations. Air supremacy suddenly shifted once more into German hands. In September the Germans destroyed 123 French and British aeroplanes and lost 27. Boelcke’s Jasta 2 was the most effective instrument in changing the balance. Between 17th September, when it first went into action — by which time its commander had amassed 25 victories — and 31st October, it lost a mere 7 machines while bringing down 76 British. Two other Albatros Jastas, Nos I and 3, had been formed and were soon operational. In October the total Allied — mostly British — losses were 88; the enemy’s, 12. By the next month the number of Jastas had increased to seven.

Jasta 2’s operational record got off to a flashing start on its very first patrol. The day was 17th September. The objects of the Jasta’s attention were eight BE2Cs of 12 Squadron and six escorting Fees of No. II, on their way to bomb the railway station at Marcoing, deep behind the enemy line. As the antiquated BE2Cs waddled in for the attack, the Germans pounced and shot down two of them and two scarcely less vulnerable fighters. Richthofen bagged an FE2B. He had as much cause to take pride in this as a man with a pistol would have for vanquishing a boy with a peashooter. Delighted at what he had accomplished, he landed by the wreck and helped to extricate the mortally injured pilot, Lieutenant L. B. F. Morris, and observer, Lieutenant T. Rees: both of whom died within minutes. In celebration, he wrote to a Berlin jeweller to order a silver cup engraved with the details of his “victory”: date, time, place, type of enemy aircraft, name of pilot. He perpetrated the same diseased act of bad taste, in concession to his psychopathic delight in killing, after each of his successes. It was also his morbid habit to scavenge the wreckage of aircraft he had destroyed for souvenirs with which to adorn his mess and a room in his parental home entirely dedicated to this unwholesome display. Some trophies were even, in execrable style, exhibited over his parents’ front door. From the site of his first kill in the air, he took the FE2B’s machinegun. The whole nasty business reeked of the custom among other savages of decapitating their enemies and shrinking their heads.

The Germans’ rejoicing was not unblemished. On 28th October two of Lanoe Hawker’s 24 Squadron pilots, Lieutenants Knight and McKay, were far behind enemy lines when Boelcke and his Jasta, Albatros D2s, intercepted them. The Combat Report specifies that twelve Halberstadts and two small Aviatik Scouts attacked the pair of DH2s. The two Britons at once began to circle tightly, which confused the enemy. In the latter’s general disorder, the Jasta’s oldest member, thirty-seven-year-old Erwin Böhme, whom Boelcke had specially selected, got in Boelcke’s way as Boelcke attacked Knight. “After five minutes’ strenuous fighting” these two Albatroses collided. Bohme’s left wing crashed into Boelcke’s right wing and sent Boelcke’s aircraft down out of control in a steepening glide which ended in a crash that killed him.

The RFC suffered a comparable blow less than a month later. On 23rd November, Hawker, patrolling at 6000 feet behind the German trenches, with Captain Andrews and Lieutenant Saundby, saw two enemy two-seaters; at which Andrews dived. Let the Combat Report take up the story: “… and then, seeing two strong hostile patrols approaching high up, was about to retire when Major Hawker dived past him and continued the pursuit.

“The D.H.s were at once attacked by the H.A., one of which dived on to Major Hawker’s tail. Captain Andrews drove this machine off, firing 25 rounds at close quarters, but was himself attacked from the rear, and his engine shot through almost immediately, so that he was obliged to try and regain the lines. He last saw Major Hawker engaging one H.A. at about 3000 feet. Lieutenant Saundby having driven one machine off Captain Andrews’s tail, engaged a second firing three-quarters of a double drum at 20 yards range.

“The H.A. fell out of control for 1000 feet and then continued to go down vertically. Lieutenant Saundby could then see no other D.H.s, and the H.A. appeared to have moved away east, where they remained for the rest of the patrol.”

Richthofen’s Combat Report reads: “… with a Vickers single-seater …” Comment has already been made about the Germans’ incorrect aircraft identification. “… The crashed aeroplane lies south of Ligny Sector J. The pilot is dead. Name of pilot: Major Hawker.

“I attacked in company with two aeroplanes of the squadron a single-seater Vickers biplane at about 3000 metres. After a very long circling fight (35 minutes) I had forced down my opponent to 500 metres near Bapaume. He then tried to reach the front, I followed him to 100 metres over Ligny, he fell from this height after 900 shots.” The disparity in the heights given by the opponents is noteworthy.

In fact what happened was that Hawker, the far better pilot but in a greatly inferior machine, outflew Richthofen despite the fact that his engine was running roughly from impeded petrol flow which robbed it of full power. Richthofen had to use a huge quantity of ammunition before he finally hit Hawker in the head; his eleventh victim.

Leutnant Stephan Kirmaier succeeded Boelcke in command of the Jasta. Under his leadership it destroyed twenty-five Allied aircraft in twenty-five days. Kirmaier was a sound commander who might have achieved fame if Captain Andrews of 24 Squadron had not shot him down before he was into his stride.

Another member of Jasta 2 laid the foundation of his fame over the Somme. Werner Voss was Jewish, a tailor’s son, who had falsified his age to enlist in the hussars. He transferred to the Air Service as an observer and operated as such at the Somme until he became a pilot and joined Boelcke in September. When he made the change he was the only surviving aircrew of those with whom he had begun his operational career. This gave him so sincere a sympathy for the crews of two-seaters that he aimed always for the engine, to give their occupants a chance of survival. Everything that has been said about Voss evokes admiration.

Guynemer was the outstanding French success during this period. Wounds inflicted at Verdun had kept him out of action from March, when he had a total of eight victories, until June. On 16th July he scored his ninth. By the end of November, when the offensive had petered out, they numbered twenty-three.

The squadrons flying what are now known as interception or air superiority fighters were not the only ones embroiled in or drastically affected by the Somme Offensive.

Contact patrolling, low flying in close co-operation with infantry in attack, was a new facet of air operations. Hitherto this had been regarded as wasteful of aircrew and aircraft, and unproductive of accurate information. It had been found that there was no exceptional hazard in flying low; and prearranged signals enabled properly trained air observers to make precise reports on the infantry’s progress. Trials with yellow smoke flares on the ground showed that these could be seen at 6000 feet. The French, during their infantry attacks in late 1915, had used flares, signalling lamps and strips of white cloth laid on the ground. In April 1916 Joffre had issued instructions for the use of such means of air-to-ground signalling, and the British had adopted them.

At the Somme, troops laid strips of white cloth on the ground when they reached certain specified points. They also carried metal mirrors on their back packs, which reflected light and could be seen from the air, so that observers could follow the advance. In addition to lamp signalling, ground HQs used panels consisting of six or eight louvred shutters, painted white on one side, which operated rather like a venetian blind. By exposing the white sides, Morse code could be seen, and read by air observers.

Line patrols were flown by pairs of aircraft, to familiarise the ground forces with friendly shapes and markings, and to strafe the enemy. For the first time, fighters — DH2s — were used to clear the air ahead of advancing troops and to tempt enemy aircraft up to fight, giving rise to the term “offensive sweep”.

An important ancillary of the main battle in Flanders was strategic bombing. This was aimed at railway lines and junctions, to disrupt the delivery of ammunition and other supplies, at supply and ammunition depots in such places as Lille, Namur, Mons, and at factories in Germany.

Strategic bombing leads us back to Raymond Collishaw, the Canadian who had had to overcome so many obstacles in order to qualify as a pilot in the Royal Naval Air Service, and who became Britain’s third-highest-scoring fighter pilot. We left him at the close of 1915, awaiting shipment to England. He sailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, on 12th January 1916; made his first solo on 16th June, after eight hours and twenty-three minutes dual; flew seven types of aeroplane during training; joined No. 3 Naval Wing on 1st August, to fly the single-seater version of the Sopwith 1 ½ – strutter; and arrived in France, at Luxeuil, on 21st, September 1916. The RNAS had been active in France since the war began, but the details of its operations are outside the scope of this work. Certain of them, however, do impinge on it: as will be seen, the RFC had to turn to its sister Service for help when in dire straits.

The wing comprised two squadrons, Red and Blue. A Flight of Red Squadron had five two-seater II-strutter bombers and one single-seater fighter. B Flight had the full establishment of five bombers and two fighters Collishaw flew one of the latter. A Flight of Blue Squadron had four Sopwith bombers, two fighters. B Flight, six Breguet bombers. The wing’s operations were directed by Wing Commander Bell Davies, who had won the VC at the Dardanelles. The Admiralty seemed to know even less about aviation than the War Office: Bell Davies had a strenuous time in France convincing his masters in London that when an aeroplane’s engine failed during an operation, it could not be attributed to pilot error nor could punishment be inflicted.

Surprisingly, there were monthly meetings between the Admiralty Air Department and l’Aviation Militaire. At one of these the French had suggested that an Allied bombing squadron should be formed to raid German munition factories. More unexpectedly, the sailors agreed. What was more, they contributed an entire wing. Since the best situation for the wing was in the French sector, it was put under French operational control.

The Naval airmen shared Luxeuil airfield with the Lafayettes and the Quatrième Groupe de Bombardement, commanded by Commandant Felix Happe. This colourful character, over six feet tall with a bushy black beard, parted in the centre, and beetling eyebrows, had a lively sense of humour and was a staunch friend of No. 3 Wing. Among the fighter escadrilles selected to escort the Franco-British bombers was the Escadrille Lafayette. Naturally they and the nautics got on very well. They played baseball against each other and indulged in “some tremendous parties”, Collishaw recalled. He also commented that Whiskey, the escadrille’s pet lion mascot, “gave newcomers a bit of a start”. He says that the publicity given to the Lafayettes was unfair, when there were many more Americans flying with the RFC and RNAS, scoring more kills, winning more decorations, but receiving no public acknowledgment.

The first operation, on 12th October, was on a large scale for the times and modern in conception. The target was the Mauser factory at Oberndorf, 175 miles away. Three Wing was able to put up five bombers and one fighter of A Flight Red Squadron and five bombers and two fighters of B Flight; four bombers and two fighters of A Flight Blue, and six bombers of B Flight. Happe provided twenty bombers. The Escadrille Lafayette and twelve French-built Sopwith 11-strutters from other escadrilles would escort the raiders as far as their range allowed. Bombers and fighters of the French 7th Army would make a diversionary raid on Lörrach, well to the south of the target and near the Swiss frontier. This was a thoroughly modern stratagem intended to distract enemy fighters.

The Allied formations would take a direct route to target. After bombing, 3 Wing would make for a point north-west of Oberndorf before turning for home at 10,000-12,000 feet. The French would fly home direct. At 1 p.m. a weather reconnaissance — another modern feature — reported favourably. Fifteen minutes later six Farmans of 4th GB took off, followed by A Flight of Red Squadron at half past one and B Flight five minutes afterwards with B Flight of Blue Squadron. At a quarter past two, Blue’s A Flight and the remaining French aircraft would depart.

Cloud base descended. The last four bombers were unable to get into formation and turned back. One crashed, but there was no serious injury to the crew.

It was Collishaw’s first operation and he said that anyone who claims not to have been nervous on such an occasion has to be an insensitive idiot or to have a bad memory. One of Red B Flight’s bombers could not formate, so turned back. The five remaining pilots, Collishaw among them, were all Canadians. Crossing the lines, they met flak, but no one was hit. At 3000 feet three enemy fighters attacked. Collishaw engaged one, his engine cut out after he had fired, he lost 2000 feet and had to return to base. The four bombers of Blue Squadron’s A Flight turned back after failing to make formation. Its B Flight found difficulty in climbing to 10,000 feet and did not cross the lines until half past three. By then most of the rest were arriving at Oberndorf. Heavy flak brought one down and its crew was captured. Fighters attacked the remainder, which beat them off. At 4.10 p.m. they thought they were over the target, and bombed; but the town was Donau-Eschingen. One Bréguet was shot down by a fighter and another crash-landed. Both crews were taken prisoner. The Sopwith fighters of Blue Squadron claimed one German fighter destroyed and one probable.

The French lost six bombers. Several fighters crashed on landing. Most of the bomber losses were among those which the Nieuports escorted: the latters’ range was too short. Happe thereafter ceased regular daylight raids and resorted to night operations. Three Wing, with its long-range fighters, carried on with daylights.

The raid had scored several hits but caused no serious damage. Three Wing dropped 3900 pounds of bombs, of which not all were on target. Bombing from 10,000 feet with primitive bomb sights could not expect to be accurate. Total Allied losses were sixteen aircrew killed or made prisoners of war.

The Allies gave their ground forces intensive support by contact patrols and low-level strafing. For the pilots it became, in the final months of the war, the most hated and feared form of aerial aggression. Low-level attack instilled a feeling of defencelessness into infantry in their trenches. The words of a German officer convey very well what it was like to have to endure this type of assault. “The infantry had no training in defence against very low-flying aircraft. Moreover, they had no confidence in their ability to shoot these machines down if they were determined to press home their attacks. As a result, they were seized with a fear amounting almost to panic; a fear that was fostered by the incessant activity and hostility of enemy aeroplanes.”

The diary of a German prisoner of war confirms this. “During the day one hardly dares to be seen in the trench owing to the English aeroplanes. They fly so low that it is a wonder they do not pull one out of the trench. Nothing is to be seen of our heroic German airmen. One can hardly calculate how much additional loss of life and strain on the nerves this costs us.”

And an unfinished letter found on the body of its writer: “We are in reserve but cannot remain long on account of hostile aircraft. About our own aeroplanes one must be almost too ashamed to write. It is simply scandalous. They fly as far as this village but no further, whereas the English are always flying over our lines, directing artillery shoots, thereby getting all their shells right into our trenches. This moral defeat has a bad effect on us all.”

The superior performance of the Allied fighters at that time enabled their pilots to use their qualities of courage and skill to the full and win the dominance in the air that is essential for such activities.

The exploits of a pilot on No. 60 Squadron, Second Lieutenant C. A. Ridley, offer a measure of light relief amid the grimness of the Somme. His mission on 3rd August was to drop a French spy behind the German lines. Engine trouble forced them down; prematurely, but on enemy territory. For more than three weeks they managed to hide and to make their way towards Belgium, where they parted. Ridley spoke neither French nor German. Having obtained civilian clothes, he was in danger of being shot as a spy if caught. With brilliant imaginativeness, he bandaged his head, painted his face with iodine and pretended to be a deaf mute. After various misadventures a suspicious military policeman arrested him on a train. Waiting until it had slowed to some 15 m.p.h., he knocked out his captor and jumped out. After further distressing experiences he found a friendly Belgian who helped him to put a ladder against the electrified fence at the Dutch frontier and climb over. It was then 8th October. One week later he reported back to his squadron bearing a vast amount of invaluable intelligence about German aerodromes, ammunition dumps, troop concentrations and movements.

All any man can do is to try to adjust himself within the limits of constantly changing circumstances. Ridley did better than most.