A 1926 map reconstructing the tactical movements in the battle. No contemporary maps of the battlefield have been found.

General Sir Henry Clinton launched the new strategy in November 1778 by sending a force of about three thousand Redcoats, Hessians, and Tories from New York to Savannah. The Tories—New York Volunteers, two battalions of De Lancey’s New York Regiment, and a battalion from Skinner’s New Jersey regiment—totaled 855. British Regulars stationed in Florida were to enter Georgia and link up with the New York force.

Clinton landed near Savannah on December 29, rolled over outnumbered Rebel troops, and swiftly took the city. The Rebels’ stunned commander, Maj. Gen. Robert Howe of the Continental Army, crossed the Savannah River into South Carolina, leaving behind some five hundred dead, wounded, or captured.

The invasion rallied militant local Tories and awakened the vengeance of Thomas Brown, a powerful Tory leader. His East Florida Rangers joined the British invaders in Savannah and on their march to Augusta, about 125 miles up the Savannah River. Along the way Brown was wounded in a skirmish that he stirred up while trying to free some jailed Tories.

Brown was an unlikely revolutionary. He had started life in America as a young man of privilege, seemingly destined to be like many wealthy Loyalists who supported the king but did not shoulder a musket. Brown’s father, a British merchant, outfitted a ship for his son, who, at twenty-four, persuaded more than seventy people from Yorkshire and the Orkney Islands to become indentured servants and sail with him to Georgia. His enterprise won him a royal grant of a large tract of land near Augusta, which he named Brownsborough. In August 1775, while he was in his home on the South Carolina side of the Savannah River, dozens of Sons of Liberty confronted him and demanded that he support the Revolution. Brown refused, and, in the uproar that followed, shot the ringleader in the foot.

Rebels pounced on him. One struck him with a musket butt, fracturing his skull. Others partially scalped him, tarred his legs, and held them over a fire. He lost two toes to severe burns, and became known to Rebels as Burntfoot Brown. Seething for revenge, he became an obsessed Tory, determined to lead Loyalists in a personal war against the Rebels. Two weeks after he had been attacked, he was in South Carolina challenging the authority of the Patriots’ Council of Safety and beginning to recruit hundreds of men for a Loyalist force.

Brown and his supporters later fled to Florida, where, commissioned as a lieutenant colonel, he recruited the East Florida Rangers from settlements along the Georgia-Florida border. He convinced Patrick Tonyn, East Florida’s royal governor, that the Rangers couldstage over-the-border raids and act as a home guard against invaders. When General Howe began his southern campaign, Brown saw it as a signal for backcountry warfare against the Rebels and a chance for what a British official called “retributive Justice.”

Brown had seventy-two Rangers in the mixed force heading for Augusta under the command of British Army colonel Archibald Campbell. Most of the expedition’s one thousand men were British Regulars. The rest, besides Brown’s men, included New York Volunteers and a recently raised unit, the Carolina Royalists, also known as the Carolina Loyalists. The quick fall of Savannah was to be followed by an easy takeover of Augusta. But Campbell, realizing he was entering territory that was more hostile, moved cautiously.

Mounted East Florida Rangers, sent ahead, reported that about one thousand Rebel militiamen held Augusta. But as Campbell neared the town, most of the Rebels crossed the river into South Carolina. He entered Augusta and began taming the area by having residents swear an oath of loyalty to the king. After taking the oath, about fourteen hundred men received pardons for their previous Rebel allegiance. Georgia, the youngest colony, was to become the first to return to royal rule. Or, as Campbell put it, he was taking “a stripe and star from the rebel flag.”

Campbell was to manage the next phase in the southern strategy: the mass recruitment of Loyalists into military units that would help the royal government restore control of Georgia. That would start with the arrival of a British agent, James Boyd, and his Loyalist recruits.

Boyd, a South Carolina Tory, had landed with the invaders but had gone off on his own mission. Given a colonel’s commission, he was sent by Campbell into South Carolina to raise a large force of Loyalists and lead them over the border to rendezvous with Campbell in Augusta.

Boyd’s first stop was near Savannah, at Wrightsborough, a Quaker and Tory settlement named after the governor. There he picked upguides who took him to an isolated site in South Carolina, where he recruited about 350 Loyalist militiamen and headed back to Georgia. Joining Boyd along the way were 250 members of the Royal Volunteers of North Carolina, a Tory military unit formed specifically to aid Campbell in his occupation of Georgia.

Rebels who had been trailing Boyd’s band struck as the Tories were about to cross a ford of the Savannah River. In a brief firefight about twenty Patriots were killed and twenty-six captured; Boyd lost about one hundred men to Rebel gunfire and desertion but kept moving. Living off the land by plundering Rebels’ farms and getting help from Tories, Boyd made his way to Augusta. He did not know that Campbell, facing a growing Rebel presence, had retreated back to Savannah.

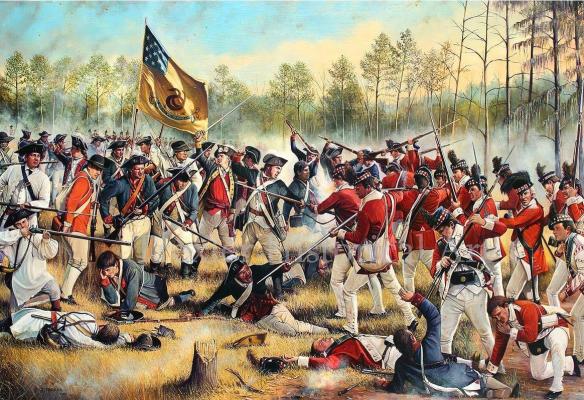

On February 14 Boyd set up camp at Kettle Creek, some fifty miles northwest of Augusta. Again, Rebels were on his trail. About 340 South Carolina and Georgia militiamen came upon Boyd’s men as they were slaughtering stolen cattle. In a surprise attack a bullet felled Boyd, who died a few hours later. Nineteen other Tories were killed; Rebel losses were seven men killed and twenty-two wounded. Most of the Tories fled. About 270 escaped to British lines. Some 150 other Tories were eventually captured either near the scene of battle or back in their own communities. Seven were hanged.

Most of Campbell’s fourteen hundred oaths of allegiance were not genuine. Faced with the choice of having their property confiscated or signing, people signed—and quickly found a Patriot leader to whom they denounced the pledge. Many signers showed their faith by joining Rebel militias and hunting down Tories. Campbell would later complain about “irregulars from the upper country [of Georgia] under the denomination of crackers, a race of men whose motions were too voluntary to be under restraint and whose scouting disposition [was] in quest of pillage.” The crackers, he reported, “found many excuses for going home to their plantations.”

The victory at Kettle Rebel Creek gave heart to the Rebels and, to the British, proof that a Loyalist call to arms would not produce an army big enough to suppress the rebellion. But the Patriot victory did not stop the southern strategy. A quixotic attempt in October 1779 to retake Savannah with a joint American-French operation ended with the French losing 635 men and the Patriots 457 while the British and Loyalist defenders saved the city at a cost of fifty-five lives. “Such a sight I never saw before,” a British officer wrote. “The Ditch was filled with Dead … and for some hundred Yards without the Lines the Plain was strewed with mangled Bodies.”

Next came General Clinton’s siege of Charleston, which ended on May 12, 1780, when Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln bowed to civilian pleas by surrendering his army of nearly six thousand Continentals and militiamen. Among the victorious Clinton troops were 175 Loyalists in a special temporary corps called the American Volunteers under the command of Capt. Patrick Ferguson of the 70th Regiment of Foot. Thirty-four of the Volunteers came from the Prince of Wales’s American Regiment. Only ten would still be alive or serving within fifteen months of their sailing to the South. Most of the replacements would be deserters from the Continental Army.

As Clinton was taking over Charleston, he asked James Simpson, the former South Carolina attorney general, how widespread and deep was the colony’s apparent euphoria over the surrender. Simpson made his own public opinion poll and reported that the population was divided into four classes: those, especially the wealthy, who were pleased to see South Carolina again under royal rule; those who had been duped by the Rebels, regretted their failings, and now supported the king; those who were repentant ex-Rebels; and those who were still Rebels and unrepentant. Simpson summed up by saying that “in drawing a comparison between the four Classes, the number and consequence of the two first by far exceed the last.” Loyalists in general, he said, were “clamourous for retributive Justice.”

Clinton set up a model for the governing of “conquered” territory: a military government that put trusted civilians in local offices, regulated prices on goods purchased by the army, and created militias for local defense. When Governor Wright returned he found he had little power. Clinton had, for example, appointed Simpson Charleston’s superintendent of police.

The militias included a home guard of older men and a regular militia of younger, unmarried men who would serve away from their homes in Georgia and North Carolina. They would be given the same pay and provisions as the king’s troops. All able-bodied free males, generally between the ages of fifteen and sixty, had to serve in a militia “any Six Months of the ensuing twelve” or provide a substitute. Militiamen were given ammunition, material for the sewing of a loose-fitting garment called a rifle shirt, and a musket if needed. Men could serve on horseback at their own expense. They were to be restrained “from offering violence to innocent and inoffensive People” and insulting or outraging “the Aged, the Infirm, the Women and Children of every denomination.”

The rules for establishing the Loyalist militias were developed by the deputy adjutant general of the British Army, the brilliant, newly promoted Maj. John André, and another new major, Patrick Ferguson, inventor of the Ferguson breech-loading rifle, which could fire four shots a minute. Ferguson, born in Scotland in 1744 and a soldier since the age of fifteen, fought in the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777. While he led a rifle company whose men were firing the weapon he invented, a Continental’s musket ball shattered his right elbow. He would never be able to bend that arm again. He returned to duty in May 1778 and learned to shoot, fence, and wield the saber with his left arm. He raised the American Volunteers, trained in the kind of ranger warfare developed by John G. Simcoe and Banastre Tarleton.

Ferguson was appointed inspector of militia, supervising the recruitment and training of the hundreds of Tories who were signing up to serve the king. He raised a regiment of 240 men at one outpost, teaching them to follow signals from his silver whistle so they could get orders even when he was not seen. “There is great difficulty inbringing the militia under any kind of regularity,” he wrote. “I am exerting myself to effect it without disgusting them.”

Tarleton, the brash young captor of General Charles Lee in 1776, earned fame as an aggressive leader of hard-driving cavalrymen on raids in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. As the commander of the Loyalist British Legion in the Carolinas, he fought fiercely and earned a reputation for showing no mercy in battle.

Under the terms of Charleston’s surrender each surrendering Rebel was made a prisoner of war. But only officers and men of the Continental Army would be confined; all civilian males and militiamen in Charleston were allowed to return to their homes after vowing not to take up arms again. Surrendering militiamen in backcountry garrisons, such as Ninety Six, were treated the same.

Throughout the South, the war between Tory and Rebel had been pitiless from the beginning. Letters, diaries, and petitions for pensions are studded with casual references to hangings. A militiaman from Rowan County, North Carolina, in his petition for a pension, for example, says “the company took several Scots Tories and there hung one of them.” He also tells of a Tory who was shot after a hasty courtmartial. The life of another was spared. But he was “condemned to be spicketed, that is, he was placed with one foot upon a sharp pin drove in a block, and was turned round … until the pin run through his foot. Then he was turned loose.”

In a rare event, a Loyalist was put on trial and accused of running his sword through wounded Rebels on a South Carolina battlefield. When a judge who had recommended mercy left the courtroom, “fathers, Sons, & brothers and friends of the slain prisoners” seized the accused, took him on horseback “under the limb of a tree, to which they tyed one end of a rope, with the other round his neck, & bid him prepare to die; he urging in vain the injustice of killing a man without tryal, & they reminding him, that he should have thought of that, when he was slaughtering their kinsmen. The Horse drawn From under him, left him suspended til he expired.”

Tories executed countless Rebels, whether or not they strictly came under Cornwallis’s order that “every Militia Man who has borne Arms with us and afterwards joined the Enemy shall be immediately hanged.” Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, commander of the Continental Army’s Southern Department, found in the South a war in which “the Whigs and Tories pursue one another with the most relent[less] Fury killing and destroying each other wherever they meet. Indeed a great deal of this Country is already laid waste & in the utmost danger of becoming a Desert,” in which the fighting “so corrupted the Principles of the People that they think of nothing but plundering one another” and committing “private murders.”

The intestine war was stoked by the kind of combat that Banastre Tarleton waged—a slashing, burning, ruthless crusade that knew no mercy. Tarleton’s American Legion grew out of the green-uniformed Queen’s American Rangers, founded by John Graves Simcoe, a young

English officer. Simcoe, wanting a mounted strike force, melded the Pennsylvania Light Dragoons, the Bucks County Light Dragoons, and a band of Scotch-Irish Tories, the Caledonia Volunteers, into the British Legion, which soon became known as the Tarleton Legion.

Loyalists of North and South Carolina eagerly joined the legion, swelling its ranks at times to a force of nearly two thousand men. Among the recruits were two sons of Allan and Flora MacDonald. The legion galloped off on numerous raids, destroying Rebel supply caches, foraging for food and horses, and earning fame and loathing.

When Major General Lincoln surrendered Charleston, the largest Continental force in the South was a detachment of about 350 Virginians commanded by Col. Abraham Buford. He was ordered to go to an American outpost at Camden, South Carolina, carry off what he could, destroy the rest, and then take his men to North Carolina.

Tarleton and 270 men pursued Buford. On May 29, 1780, they caught up with him at the Waxhaws, as the settlement near Wax-haw Creek was called, about twelve miles north of Lancaster, South Carolina. Tarleton, claiming to outnumber Buford, asked him to surrender under terms similar to what Lincoln had accepted. Buford refused, and the battle began, possibly before Tarleton’s flag of truce had been withdrawn. Tarleton’s horse was shot from under him as he and his dragoons rode down on Buford’s men. Undaunted, Tarleton jumped on another horse.

Exactly what happened in the battle and afterward will never be known. Buford and eighty or ninety men—most of them mounted—escaped, meaning that the killed and wounded may have totaled more than three hundred. This would be an unprecedented battle casualty rate of 70 to 75 percent. The outcry against Tarleton—” Bloody Tarleton,” “Butcher Tarleton,” “Bloody Ban”—was inspired by what Rebels believed happened after the battle.

Dr. Robert Brownfield, a surgeon attached to Buford’s regiment, later wrote that a request for quarter was refused and survivors said that “not a man was spared.” Tarleton’s men “went over the ground plunging their bayonets into every one that exhibited any signs of life.” One man had his right hand hacked off, suffered twenty-twomore wounds, and was left for dead; he lived to report the bayoneting. News of the massacre swept through the South, and Rebels’ retaliatory savagery was accompanied by the cry “Tarleton’s Quarter” or “Buford’s Quarter.”

After two disastrous defeats of the Continental Army in South Carolina—Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln’s mass surrender at Charleston in May 1780 and the rout of Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates’s large force at Camden in August—Cornwallis planned a march to Virginia. Georgia was under royal rule, and vast tracts of the Carolinas were controlled by a British-Loyalist regime. By September there was no large concentration of Continental Army troops anywhere in the South. John Rutledge, the Rebel governor of South Carolina, was trying to govern his state from Hillsborough, North Carolina. And some timid Rebels were suggesting that the time had come to simply let all three of those states go back to colony status under their conquerors. From the British viewpoint the king’s forces and friends were snug in the South, their flanks covered by the sea to the east and the mountain barrier to the west.

Beyond the mountains was the domain of the Overmountain men, colonists who had defied King George’s 1763 proclamation that prohibited settlement west of the mountains. The Overmountain men, most of them Scotch-Irish, had not paid much attention to the Revolution until the British and their Tory allies began fighting southern Rebels. Now, as General Cornwallis was advancing northward, Overmountain Rebels were attacking British and Loyalist outposts.

Ferguson and his Volunteers were protecting the western flank of Cornwallis, who was mounting an invasion of North Carolina. Deciding to challenge the Overmountain men, Ferguson sent a Rebel prisoner into the mountains with a warning: If the Rebels “did not desist from their opposition to the British arms, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword.”

In outraged response, at a frontier outpost on the Watauga Rivercalled Sycamore Shoals, the mountain Rebels quickly assembled a makeshift mounted army that grew on the trail until it numbered about one thousand men from Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia, with officers elected on the spot. There was no military structure or wagon train of supplies, though the group was at its core an authorized Virginia militia. The men carried what they needed and prodded cattle along the way for food on the hoof. Most of them did not have muskets, but long-barreled, small-caliber American rifles, for they were more hunters than soldiers. Setting off not to fight for a nation but to defend their cabins by the streams and their patches of cotton and corn, they headed across the mountains in search of Ferguson.