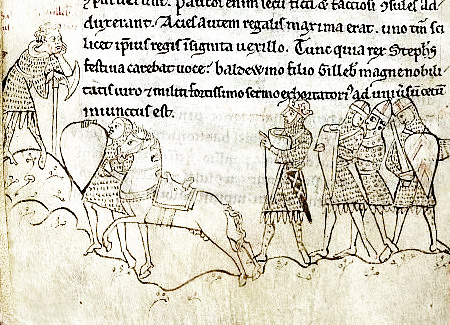

Near contemporary illustration of the battle of Lincoln; Stephen (fourth from the right) is listening to Baldwin of Clare orating a battle speech (left).

It is the terms on which the castle of Lincoln was held which are the key to the controversy that blew up so suddenly during the Christmas feast of 1140–1. It is clear that Stephen had recently granted the constableship of the castle to Ranulf of Chester. A later charter of Stephen sought to reinstate Ranulf in the position he had enjoyed before the battle of Lincoln. When (and if) he could do so: “then there shall remain to the king the tower and the city of Lincoln, and to the said earl there shall remain the tower which his mother had fortified along with the office of constable of the castle of Lincoln and of Lincolnshire by hereditary right.” As the charter here states and as can still be seen, there were, unusually, two keeps or towers within the castle enclosure, and one of them in 1140 and long thereafter was known as Lucy’s Tower. Put a little over-simply, Lincoln had a castle that was at the same time both royal and seigneurial. To add to the complication, the bishop – only very recently restored to the king’s favour – had reputedly turned his own cathedral church “into a castle.” While this may often be a loose phrase, in this case archaeology and architectural history support it. The bishop was also building a new palace to the south and east of the cathedral, having obtained permission to demolish part of the walls of the upper city to make room for it. In this crowded building site, with so many centres of power so close together and so loosely differentiated, it did not take much to provoke a confrontation. What seems to have inaugurated it was a complaint from the citizens of Lincoln, in this case in league with the bishop, that the brothers were inflicting unaccustomed burdens on them. Whether or not the complaint was fair, it supports the view that the brothers were acting in some official capacity. The king, who had granted the offices, the constableship to Ranulf and the earldom to William, now had second thoughts. He asked for the castle back and it was perhaps in response to this that rather than surrendering Lucy’s Tower Ranulf expelled the garrison of the royal tower. The king marched fast up Ermine Street and at some point within the the twelve days of Christmas he arrived in the city unannounced.

Ranulf of Chester managed to effect his escape from the castle and retreated to Chester. He sent messengers to Robert of Gloucester, his father-in-law, in the west country. He promised in return for help to accept the empress and swear fealty to her. Not all in the empress’s camp were convinced by his protestations, for – and this would be a cross that he would continue to have to bear – he was not trusted, having for some time appeared neutral in his loyalty. It suited Robert of Gloucester, however, to respond to this appeal. Peace discussions had just failed. The accession of Ranulf of Chester offered important new territory and resources to the empress’s party, particularly if his position in Lincolnshire could be defended. So Robert of Gloucester, along with Miles of Gloucester, “and all who had armed themselves against the king,” set out, though they travelled along minor roads and their intended destination was not at first revealed to the majority of the army. At some point, possibly at Castle Donington in Leicestershire, they met up with Ranulf of Chester. From there the most obvious route would have taken them across the Trent at Newark – Robert of Leicester’s castle garrison would have had neither the numbers nor any incentive to try to stop them – and thence along the Fosse Way to Lincoln. The twin towers of the castle and, more prominent still, the cathedral with its fortified west front, would be the first glimpses they gained as they approached the city from the south-west. There is no mention of the bridge over the Whitham either before or after their arrival, so it may have been destroyed to delay their passage. If so, the tactic was not successful, for a fording place was found a little to the west.

While it might help the drama to see this army fighting its way across and immediately engaging the king’s forces, it seems that the confrontation was more deliberate than this, and that it was not until the day after their arrival at the earliest that the battle was fought. It is certain that it took place on an important feast day, that of the Purification of Our Lady, on 2 February 1141. The king’s defeat on this day almost demanded a suitable portent, and it was found in the liturgy. The king had attended mass in the cathedral church, celebrated by the bishop, Alexander, whom a few months earlier he had threatened to depose. This was the Feast of Candlemas, in which candles were blessed, carried in procession, and held up alight by the congregation for large parts of the service. It was widely reported that the king’s candle had cracked and gone out and had to be relit. The king would have heard more than once during the service the words of Simeon as he cradled the infant Christ in his arms. “Now Lord let thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word.” As Stephen emerged from the cathedral porch and looked across to the castle, he could have reflected that his own days might be numbered and his end very far from peaceful.

By this date both sides – those envisaged at prayer within the cathedral, and those outside the city walls – had significant forces at their disposal. Those “who had armed themselves against the king” included the “big three,” Robert of Gloucester, seen as the leader, Miles of Gloucester, and Brian Fitz Count, along with “the disinherited,” chief among them Baldwin de Redvers, and Ranulf of Chester along with his brother William de Roumare. Ranulf had brought with him “a dreadful and unendurable band of Welshmen,” but this degrades them, for they were led by three kings, Madog ap Maredudd of Powys, Cadwaladr ap Gryffyd ap Cynan, and Morgan ab Owain of Glamorgan, and their trained troops may have had a decisive impact on the battle. The king’s support had built up over the previous few days. A charter which he issued in favour of Bordesley Abbey, a foundation of Waleran of Meulan, earl of Worcester, has the following lay witnesses: William of Ypres, Hugh Bigod, Baldwin Fitz Gilbert, Ingelram de Say, Richard de Courcy and Richard Fitz Urse. These men had been with him from the time of his arrival, and by the time of the battle several other earls and quite a few of the northern baronage had joined them. Along with them was the archbishop-elect of York, William the treasurer, who was given the temporalities of the see by the king, and might have kept them had the outcome of the day been different. There were reportedly divided counsels. Some advised the king to wait for reinforcements. But it seems clear that he already had a substantial army, fully the equal in numbers of that opposing him: had there been an obvious imbalance, battle would never have been offered. Still, the decision to fight was the king’s own. He had backed away before and was a man conscious of his reputation. He could hope to enjoy a moral advantage, for it was treasonable to confront an anointed king in the field.

Henry, archdeacon of Huntingdon, was here on home territory and before his account of the battle he gave speeches to the leaders of both sides. This is a rhetorical device but still it gives a view of the issues involved and the reputation of some prominent individuals. The king himself was softly spoken and so his address to his troops had to be delegated to Baldwin Fitz Gilbert. The royal troops, so they were assured, had right on their side, they were “the faithful against the faithless, those who remain true against those who are false.” Nor if they considered the leadership qualities of the opposing generals did they have anything to fear. Robert of Gloucester was a blackguard, “with the mouth of a lion and the heart of a rabbit,” while Ranulf of Chester was a loose cannon, “impetuous in battle, careless of danger, with designs beyond his powers, passionate in his pursuit of the impossible,” and the Welshmen whom he led were poorly armed and had no discipline. On their own side, by contrast, were many earls and barons born and bred to feats of arms. The day would assuredly be theirs.

The speeches given to the opposing army, however, painted these same earls in a much less favourable light, as men possessing their full share of the weaknesses reported of some of the aristocracy in any age. So at least Robert of Gloucester, who named six earls, with not a good word to say of any of them. Alan of Brittany was simply detestable, unrivalled in his cruelty. Waleran of Meulan was more devious, “the last to muster, the first to decamp, slow to attack, quick to retreat,” a twelfth-century precursor of W. S. Gilbert’s Duke of Plaza-Toro. Then there was Earl Hugh Bigod, the arch-perjurer, for not only had he broken his oath to the empress but he had affirmed “that King Henry had granted the kingdom to Stephen and set aside his daughter.” The count of Aumale was a bounder and a cad: “because of his intolerable filthiness his wife left him and became a fugitive,” only to fall on the rebound into the hands of a man even worse, a notorious adulterer and hopelessly addicted to the bottle. Neither the man nor the unfortunate lady are named, but by elimination this would seem to refer to William de Warenne, earl of Surrey. The last of the six earls was William of Ypres, a bête noire of the empress’s supporters, for they knew of his importance to Stephen’s cause. These men were all perjurers, as were the lesser men who supported them. Robert of Gloucester was fighting – the case is rehearsed yet again – against a king who had cruelly usurped the realm, “contrary to the oaths which he swore to my sister.” The king could certainly not claim any moral superiority.

The royal forces offered battle. The exact place cannot be identified, but it must have been an open space, perhaps to the north or (more probably) the west of the city, seen as suitable for feats of arms. They started “with that prelude to the battle that is called jousting, for in this [the royal forces] were accomplished.” It is possible that they expected the empress’s forces to withdraw at this point; battle had not been joined and so no honour had been lost; but if so they were disappointed. Again it is Henry of Huntingdon who is the best informed and he manages to give some structure to the battle. The empress’s supporters formed up in strict classical formation in three squadrons. At the centre there were “the disinherited,” among them Baldwin de Redvers, though no leader is named for this group. On the one flank there was Ranulf of Chester with his Welsh auxiliaries outflanking his own troops, while on the other there was Robert of Gloucester, dux magnus. The royal forces were disposed rather differently. The king placed himself at the back of the field, and fought on foot, surrounded by his household troops, also on foot – their horses were led away – for their greater security. In front was his cavalry: not his own troops but those brought by his earls, but these “false and factious earls” had brought limited forces with them. The mercenaries were under the command of William of Ypres, accompanied by at least one of the northern earls, and these would face Ranulf of Chester and the Welsh. The initial cavalry charges seem to have been decisive. “The disinherited” attacked those who had it all, the royal earls, and the king’s forces were routed, their leaders fleeing the field. The troops under William of Ypres initially had greater success, forcing the Welsh auxiliaries into retreat, but they in turn were routed when Ranulf of Chester turned on them. William of Ypres then retreated, for by now the result was not in doubt: “as he was a great expert in warfare, he saw the impossibility of assisting the king and reserved his aid for better times.” With the result clear and given the high status of many who remained in the field, the second stage of the battle was less bloody and more deliberate, being devoted to the taking of prisoners. The king himself was the chief prize and was reported to have surrendered only after the most heroic struggle. He had been given a double-headed axe, a true Viking weapon, by one of the citizens of Lincoln, and with this he laid about him to good effect, killing several men. He had secured a reputation for bravery, but had lost the battle. Finally, late in the day, he was surrounded and overpowered, his captor, William de Cahagnes, crying out in the melee: “Come here everyone, come here. I’ve got the king!”So he had. Stephen would not surrender to a simple country knight but was brought before Robert of Gloucester and surrendered to him.

In the aftermath of the battle no attempt was made to prevent the common soldiery from looting the city of Lincoln and slaying any of the citizens who had stayed to defend their property. The majority fled in panic and they were no more fortunate, for many of them died when overloaded boats overturned and their occupants were drowned. In total, “according to some estimates about five hundred of the chief citizens perished.” The victorious warriors claimed to have right on their side, referring particularly to the “right of storm” which governed the treatment of towns taken after a defence. It was stretching it more than a little to apply it in this instance and the main reason for the looting was simple greed. Still, William of Malmesbury comments, neither victors nor vanquished had any sympathy for the citizens, “since it was they who by their instigation had given rise to this calamity.” This is a chilling phrase and somewhat surprising at first sight coming from a cleric, one who might have been expected to sympathize with the sufferings of the poor. It gives an early indication of what would prove an important subtext in his treatment of towns and townsmen. Whilst he gave them their proper dignity as “citizens,” in the circles for whom he wrote they were taken down a peg and became simply “burgesses.” The party of the empress was showing itself to be anti-mercantile, opposed to any manifestation of municipal liberty. Their feelings are quite understandable but for a party with pretensions to government they were ill advised. In any subsequent dealings they had with the major cities this reputation would come before them.

Along with the king on 2 February 1141 there were captured “a few barons of notable loyalty and courage.” They were more fortunate than the citizens of Lincoln. The northern chronicler, John of Hexham, gives quite a long list: Bernard de Balliol, Roger de Mowbray, Richard de Courcy, William Fossard, William Peverel, William Clerfeith (though he later escaped), and Gilbert de Gant. Baldwin de Clare, Richard Fitz Urse, Ingelram de Say, and Ilbert de Lacy were also mentioned in dispatches. It would appear that while the earls had turned tail many of the baronage had stood firm. The northern barons seem to have been particularly resolute. The presence and the tenacity of these men are explained in large part by the way that their interests were threatened by the brothers Ranulf, earl of Chester, and William de Roumare, the new earl of Lincoln. The Humber estuary was a thoroughfare not a boundary, and all but a few of the major tenants in Yorkshire had significant holdings in Lincolnshire also. Roger de Mowbray was the main landholder in Gainsborough, where William de Roumare “had built his castle” and had its tenure confirmed to him by the king; Gilbert de Gant held lands at Folkingham and at Barton-upon-Humber, and his uncle Robert was the king’s chancellor. Royal favour to the brothers late in 1140, taken along with the recognition that the north midlands was now the frontier between the two parties, had destabilized the region. None of the men taken captive was detained for very long. The empress would now pursue her claim to be the rightful ruler of the kingdom. It was not in her interest to weaken the defence of its northern borders, as would assuredly have happened had all these men remained in captivity. And she had the main prize.

The king was brought in captivity, accompanying the core elements of the army that had defeated him, to the west country. Robert of Gloucester took personal responsibility for his safety. They came first to the royal city of Gloucester, arriving on 9 February, a week after the battle. There the king was “presented” to the empress. If they did converse, that conversation can only have been on familiar lines. The king was kept at Gloucester for a short time but then moved to Bristol. That castle was quite used to receiving high-status guests. It was there that Robert, duke of Normandy, had been kept during the last phase of his long captivity, from 1126 to 1134, when he died. Robert had been moved there “on the advice of [the empress] and that of David king of Scots, her uncle.” So also in the case of Stephen. Bristol was the more secure base, which Stephen himself had not been able to take earlier, and it was a seigneurial castle not a royal one. The king was kept there “at first in a manner that was honourable, except that he was not allowed to leave his quarters,” but then, because he over-stepped the boundaries appointed for him, “he was kept in chains.” There was every reason to believe that he would die in captivity, just as Robert, duke of Normandy, had done. Even so, he remained the king of England, a necessary point of reference in all political discussion.