The beginning of Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty marked the beginning of the so-called New Kingdom and a true golden age.

Its first monarchs were Ahmose I (c. 1550–1525 BC), ‘Lord of the Two Lands’ and ‘Son of Ra’, and his sister-wife Ahmose-Nefertari, ‘Lady of the Two Lands’, ‘Daughter of Ra’. And since ‘she was heir with her husband to her father Seqenre’s holdings’, she shared in the decision-making process.

This included plans to honour their joint grandmother Tetisheri with a cenotaph, Ahmose confiding that he ‘desires to build for her a pyramid and chapel in the sacred land’ of Abydos, part of the last royal pyramid complex to be built in Egypt.

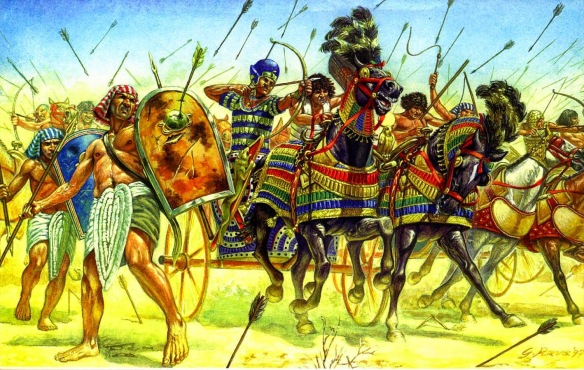

Featuring a terraced temple in the desert cliffs, linked to the pyramid of Tetisheri by a kilometre-long causeway, this terminated with the couple’s own fifty-metre-high cenotaph pyramid, whose surrounding complex featured scenes of tightly massed archers, horses, chariots and fallen Asiatics bearing the names of both King Apophis and the city of Avaris itself.

These images documented the last stages of the War of Independence and the siege of Avaris, and were dominated by the five-foot (1.5-metre) king, transformed here into ‘superhuman Ahmose’. Seizing both victory and the red crown of the north, which he wears on his triumphal return to Thebes to give thanks to Amen at Karnak, Ahmose succeeded in pushing out the Hyksos in the eleventh year of Apophis’s successor Khamudi.

According to an eyewitness account contained in the el-Kab tomb of one of his officers, ‘Ahmose son of Ebana’ (differentiated from his king by using his mother Ebana’s name), officer Ahmose had accompanied his king to Avaris, fighting alongside him in close combat and cutting off the hands of those he killed to keep a tally of his dead. By this late stage of the campaign, the Egyptians had certainly gained the technical advantage, for their sharp weapons of alloyed bronze contrasted with the unalloyed copper available to the Hyksos, whose supplies of imported tin had apparently been cut off.

Following the Egyptian victory, the Hyksos were allowed to leave Egypt and, as evidence from excavations at Avaris supports this ‘mass exodus’, later historians also refer to the ‘departure of the tribe of Shepherds from Egypt to Jerusalem’.

Yet it was no clean break, and King Ahmose’s Egyptians pushed north, taking the Hyksos stronghold Sharuhen in Palestine after a lengthy siege. By around 1527 BC, the king had reached Naharin (also known as Mitanni) in Syria, establishing Egypt’s border at the River Euphrates. His conquest of the eastern Mediterranean coastline also led to an alliance with Egypt’s long-standing trading partners Crete, the foremost sea power of the time.

But tackling the Hyksos was only part of Ahmose’s task. For ‘when his majesty had slain the nomads of Asia, he sailed south to destroy the Nubian bowmen and made great slaughter among them’. He visited Buhen and its new temple to Horus with his mother Ahhotep and sister-wife Ahmose-Nefertari, and even extended this southern border as far as the Sai Island fortress, where Ahmose’s statue was placed permanently on guard.

Finally, with Egypt’s boundaries both expanded and secured, Ahmose could focus his attentions on his motherland, starting with rebuilding projects at Memphis and Heliopolis. Having been razed to the ground, Avaris was also rebuilt and reclaimed as part of Egypt under the new name ‘Perunefer’, its defensive walls and huge grain silos sustaining a population of Egyptian troops, Nubian and Aegean mercenaries, Syrian and Minoan shipwrights and a stockpile of provisions for future campaigns.

Restoration work was also required down in Thebes, after a serious storm damaged Karnak. So Ahmose presented a rich haul of treasure, from vessels of gold and silver that passed down as heirlooms for 500 years, to new gold diadems and necklaces for the temple’s statues.

Such regalia was also worn by the royal women; the monarchs’ mother Ahhotep, now approaching her eighties, and her daughter Ahmose-Nefertari, who inherited her mother’s role as ‘God’s Wife of Amen’. This brought massive wealth and prestige, as did her appointment as ‘second prophet of Amen’ – deputy high priest.

When carrying out her duties at Karnak, Ahmose-Nefertari was, like all clergy, required to bathe in the temple’s sacred lake and don pure linen robes. She then led the sacred processions with the king or his deputy, the high priest, the only ones allowed to enter the innermost shrines to give the gods their daily offerings. The role of God’s Wife also involved the ritual burning of enemy images, the firing of arrows into ritual targets and the manual stimulation of Amen in her capacity as ‘the Hand of God’. For Amen often displayed the same virility as Min, whose erect penis was regularly anointed with Min’s favourite, honey-based ‘sweet ointment’.

Ahmose-Nefertari’s own fertility was impressive too. She had three daughters and at least two sons, one of whom was Amenhotep; his selection as royal heir elevated her own status to ‘King’s Mother’, which, combined with her status as ‘King’s Daughter’, ‘King’s Sister’ and ‘King’s Wife’, imbued her name with great power. Her cartouches were written at either side of those of her brother-husband Ahmose as if to protect it, and this idea was replicated in scenes where Ahmose-Nefertari protectively embraces her husband while her mirror image embraces their son.

When the battle-hardened, if slightly arthritic, King Ahmose died around 1525 BC, aged around thirty-five, his wife oversaw his burial in a rock-cut tomb at Dra Abu el-Naga. His curly hair was thickly coated in the same ‘abundant layer’ of conifer resin that had been applied to his body, a contemporary medical text even specifying ‘the umbrella pine of Byblos’. The use of this deluxe preservative made a permanent statement that Egypt was once more in control of the regions that produced such a substance, with the king literally immersed in the essence of lands he now controlled.

With their son Amenhotep I (c.1525–1504 BC) still a young boy at his father’s death, Ahmose-Nefertari ruled as regent and, even when her son was king, married to his sister as per family tradition, his mother remained his co-ruler, as she would for the rest of his reign.

Her power had long been established at Karnak on Thebes’s East Bank, while on her personal estates on the West Bank she set up a training college for priestesses. Mother and son were also acknowledged as joint founders of the nearby village of Deir el-Medina, which housed those who built the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. The monarchs were more popular here than Amen and their statuettes were the focus of private worship in the houses as well as in the daily rites of the village temple, where the workers consulted them as oracles, asking ‘Shall we get our rations?’, ‘Shall I burn it?’, ‘Will she get her place?’ The villagers even honoured their beloved founders with an annual festival involving ‘four solid days of drinking’.

Now the villagers’ official role was to build the royal tombs, which were traditionally begun early in the reign to give sufficient time for completion. The advice given by scribe Ani ‘of the palace of Queen Ahmose-Nefertari’ was to start building a tomb when young – ‘Establish your place in the desert as a place to conceal your body, make it your business, a thing of importance . . . Do it and you will be happy’. Since Amenhotep was still a small child at his accession, it is more than probable that his mother, the regent, gave the orders for work to begin on her son’s tomb.

Yet in a departure from established practice, this may not have been located in the family plot at Dra Abu el-Naga, but was quite possibly built in the Valley of the Kings, which lay beyond. And the tomb she ordered was most likely the one now designated KV.39 (the thirty-ninth tomb to be discovered here). It is certainly the highest tomb in the valley, lying closest to the pyramid-shaped peak of el-Qurn, the home of Meretseger – ‘She who loves silence’ – the cobra goddess whose representatives are still very much alive in the form of the snakes that live here.

The tomb was finally excavated in the late twentieth century, when the lead archaeologist claimed it ‘was the first to be built in the Valley of the Kings’. The royal architect ‘Ineni may have been called to work on the tomb of Amenhotep I, a tomb not yet established with certainty but most likely KV.39’, whose chambers were left plain in the style of royal tombs of this time, while its two burial chambers were quite possibly intended for Amenhotep I and either his mother or other family members.

Unlike previous royal tombs, many of which had already been robbed, the entrance to KV.39 was hidden away in an attempt to maintain its secrecy. With no chapels or places for offerings added beside the tomb to draw attention to it, mother and son were the first royals to have a separate funerary temple, built, not coincidentally, directly below the tomb in the bay of Deir el-Bahari, using bricks stamped with Ahmose-Nefertari’s name.

The trusted Ineni was also ordered to design scenes at Karnak portraying the mother and son making offerings to Amen with her son and their Eleventh Dynasty Theban predecessors – who had also reunited their country. And, like them keen to demonstrate his military abilities, Amenhotep I led a campaign into Nubia, reinforcing Egypt’s boundary at Sai Island in emulation of his father, adding his own statue beside his, before returning home laden with gold and tribute.

But then Amenhotep I died suddenly in his late twenties, his cause of death unknown; the official statement simply claimed that the king, ‘having spent a life in happiness and the years in peace, went forth to heaven and joined with the aten’, a term used since the Old Kingdom to mean circle, and by this time used to describe the sun’s disc.

Since Ahmose-Nefertari’s son had apparently left no heir, the next king was her son-in-law Tuthmosis (1504–1492 BC), and even though he had married her daughter, yet another Princess Ahmose, his cartouches were nonetheless twinned with those of the everpresent Ahmose-Nefertari, still the most important woman in Egypt.

When she finally passed away, approaching her seventies, it was reported that ‘the God’s Wife has flown up to heaven’. Her body was mummified in natron solution, and its five-foot two-inch (1.5m) linen-wrapped length placed in a coffin over twelve feet (four metres) long, to emphasise her exceptional status. She was quite possibly placed with her son in KV.39, in the second of the tomb’s burial chambers; as, it seems, were some of the other women of their family, whose battered remains, found within, had the same characteristic buck teeth as the late queen.

Posthumously awarded the titles ‘Mistress of the Sky’, and ‘Lady of the West’, Ahmose-Nefertari, as ‘a goddess of resurrection’, was portrayed with the black or blue skin that were ‘both colours of resurrection’. With her images on Karnak’s walls as potent as the gods’ cult statues, they were veiled in the manner of an icon, as revealed by their small surrounding peg holes. And as ‘divine patroness of the Theban necropolis’, she was the first deity named in the tomb-builders’ official reports, and would be featured in the later wall scenes of over fifty Theban tombs.

As their dynasty continued to expand, Tuthmosis I had at least five children by minor wives and by his queen, Ahmose, who, uniquely, is shown pregnant with her eldest daughter. Naming her Hatsheput, meaning ‘the foremost noble one’, her father Tuthmosis I apparently also named her ‘heiress of Horus’, announcing before the court that ‘she is my successor upon my throne’, warning that ‘he who does her homage shall live, he who speaks evil in blasphemy of her majesty shall die!’

As ‘Egypt’s greatest warrior king’, Tuthmosis I spent much of his eleven-year reign consolidating the vast empire he’d inherited, both in Syria and in Nubia.