If you had spoken to an expanding-state dignitary about anything like consent of the governed or plebiscites, he would have thought you out of your mind; but the million or more Silesians conquered by Friedrich at Mollwitz or in the sieges were well content to be Prussian. They were predominantly Protestant, and the Austrian Catholic officials, while not actually oppressing them, made things difficult. Moreover, Prussian administration was more efficient than Austrian; more precise, with a better sense of essential justice. Friedrich had not only made a conquest, he had secured the reconciliation of the conquered.

But there was one person who would never be reconciled to Prussia in Silesia, and that was Maria Theresa, empress and queen. She regarded Friedrich as the most wicked and dangerous man in Europe, and she said so; a reaction not merely of personal pique, but of an underlying sense that his success threatened the whole system of which she formed a part. This opinion was implemented through a long series of diplomatic and military maneuvers. In 1742, at the urging of her British friends, Maria Theresa signed a peace which turned out to be an armistice. It gave Friedrich his Silesia and allowed her to turn on the Bavarians and French. In 1743 the French were disastrously defeated in Bohemia and on the Rhine; Bavaria fell entirely into Austrian hands and Friedrich re-entered the war as the ally of France, more or less to keep the revived Hapsburg power from being turned on him alone. In 1744 he invaded Bohemia and captured Prague, but got himself maneuvered out by attacks on his communications. In 1745 the Austrians, now with Saxony as an ally, counterinvaded Silesia and were well beaten at Hohenfriedberg and Sohr, so that the peace finally signed only confirmed the verdict of Mollwitz.

In every series of campaigns certain features establish themselves on a semi-permanent basis as part of the frame of reference. In the War of the Austrian Succession one of these features was the operations of the Hungarian irregular light cavalry, pandours, who hung in clouds across the front and flanks of every Austrian army. They were barbarians who used to bum towns, raid camps, and cut the wounded to pieces when they found them, but they made communications a problem for every army opposing the Austrian, and they forced the king to fight for his intelligence of enemy movements. As a result he developed his own cavalry service on lines parallel to those given the infantry by Friedrich Wilhelm–careful training, perfect co-ordination, precision of movement–and reared up a group of remarkable cavalry officers, Ziethen, Seydlitz, Rothenbourg. This was not so much a true light cavalry, like the pandours, but an instrument for combat intelligence and battle purposes, and it was the first of its kind.

The infantry did not need improving, only an intensification of its previous status. Friedrich had discovered that his foot could not only fire twice as fast as its opponents, but also that it could maneuver much faster, and on this he based a new system of minor tactics. The infantry was to fire a platoon volley, advance four paces behind the smoke while reloading for the next volley and, when close enough to the bullet-racked enemy line, fall on with the bayonet.

In major tactics every one of his big battles of the war–Chotusitz, Hohenfriedberg, Sohr–was a deliberate repetition of the accident of Mollwitz. In each Friedrich pushed forward a heavily loaded right wing, took the enemy at the oblique, and rolled up his line. There were variations in the individual case, but this was the basic pattern, and it was noted beyond the borders of Prussia.

#

This was the military background for the next act. Part of the political background was furnished by the fact that, having obtained what he wanted, Friedrich was opposed to war. “We must get rid of it as a doctor does of a fever.” But there was now on the imperial side Wenzel Anton, Graf von Kaunitz, counselor to Maria Theresa. She had been rather reluctantly willing to accept Bavaria in compensation for the loss of Silesia, but the peace that ended the general war gave her neither, and though her husband secured election as emperor, there remained in her an inextinguishable fund of bitterness against the robber who had taken her province.

Wenzel Anton (who exercised by riding in a hall to avoid fresh air and kept dozens of kittens, which he gave away as soon as they became cats) exploited this bitterness, and he exploited it in the name of the balance of power. He argued that the presence of a new great power in north Germany–and with her army and accession of territory, no one could doubt that Prussia had become one–had deprived Austria of her proper place in Europe and freedom of action. If she was ever to recover either, if the French influence which had become so predominant in Europe through Friedrich was ever to be allayed, Prussia must be destroyed. Austria’s traditional alliance was with the sea powers, England and Holland; but it was hopeless to expect these Protestant nations to support an enterprise against Protestant Prussia. The true line of Austrian policy was therefore in forming an alliance with France and Russia, the former of whom could be repaid in the Netherlands and Italy, and the latter in East Prussia, none of which lands were really part of the empire.

Thus Kaunitz to the empress. It was not hard to talk Russia into the combination, for Russia was perpetually ambitious and, for quite personal reasons, the Russian Empress Elizabeth had conceived a deep dislike for Friedrich. France and some of the lesser states–Sweden, Saxony–came harder, but Kaunitz was a diplomat of almost uncanny skill, who had a goodie for everybody. Also he was aided by the underlying feeling he used with the empress, more a sensation than a statable idea, that the balance of power had been overthrown by the expanding Prussian state, and there was no security for anyone unless this tendency was ruthlessly punished. France signed; and England promptly allied herself with Friedrich–the sea power to furnish money, the Prussians troops for the protection of King George’s Hannover.

These were the roots of the Seven Years’ War, the first of the true world wars, itself decisive in more than one way, but whose importance is often hidden beneath the overlays of later struggles.

The actual fighting began in August 1756, when Friedrich invaded Saxony without a declaration of war, occupied Dresden, and shut up the Saxon army in an entrenched camp at Pirna. His espionage service was exceptionally good; he had a man named Menzel in the Saxon chancellery who, incidentally, was discovered and spent the remaining eighteen years of his life in irons in prison growing a fine crop of hair. Friedrich published the documents Menzel furnished as a justification for his aggression against Saxony. Not that it did much good, since the adroit Kaunitz instantly summoned the Diet of the empire and persuaded all the smaller states to send contingents to an imperial army, which made part of the half million men who began to flow in for the demolition of Prussia.

Friedrich’s aggression succeeded in its first object. Saxony was knocked out, and what was left of its enlisted troops was offered the choice of serving under Friedrich henceforth or going to prison. Friedrich invaded Bohemia for a second time, won a battle under the walls of Prague, threw a blockade around the town and pressed southward until he encountered an army twice the size of his own under Marshal Leopold Josef Daun at Kolin on June 18, 1757.

This officer was probably the best commander Friedrich ever faced. His plan was the same as that of the usual Austrian leader–draw up and await attack, since he lacked the mobility to compete with the Prussians in maneuver. But he chose his position very well, the left on a high wooded ridge, center running across little knolls and swampy pools, and right resting on another hill, with an oakwood on it and a marshy stream running past. Daun was in three lines instead of the usual two; all across the front, in reeds, woods, and tall grass, he scattered quantities of Croat irregular sharpshooters. Friedrich judged the Austrian left unassailable and angled to his own left to make an oblique attack on that wing, with each of what we would call his brigades to follow on in turn, swinging rightward when they reached position to sweep out Daun’s line. The leading formation, Hülsen’s, did break through the extreme flank and drove back the first two Austrian lines; but those that followed had to cross Daun’s front, with the fire from the Croats coming into their flank. One group halted and faced round to drive off these tormentors by firing a few volleys, and the brigade immediately behind, believing that the battle plan had been changed, also faced round and went into action.

That is, they had begun too soon, and in somewhat the wrong place. This should not have been fatal, for Friedrich had a strong column under Prince Moritz of Dessau coming up to form the link between Hülsen and the groups prematurely engaged. But Friedrich chose this moment to lose his temper and order Moritz in at once, using a form of words that caused him also to make contact too soon. The consequence was that Hülsen was isolated. The Austrians counter attacked him, completely broke up his formation, turned in on the flank of the remainder of the Prussian line, and drove Friedrich from the field with 13,000 lost out of 33,000 men.

The allies now thought they had him and began to shoot columns at him from all directions. The Prince of Hildburghausen with the army of the empire, and Marshal Soubise with the French, together 63,000 strong, drove toward Saxony; 17,000 Swedes landed in Pomerania; 80,000 Russians moved in from their side, and Charles of Lorraine, with his own and Daun’s troops, over 100,000, marched on Silesia from the south.

That summer there was fighting all around the circle, with Prussia slowly going down. The Swedes were incompetently led, accomplished nothing against the detachment that faced them, but they still forced Friedrich to make that detachment. The Russians beat a third of their number of Prussians in a battle, but their supply organization broke down, the machine ground to a halt just when it might have taken Berlin, and a large part of the army melted away in desertions. The Austrians, as might be expected, made a war of sieges, but it took 41,000 men to keep them from overrunning everything, and Friedrich could gather barely 22,000 men to meet the incursion of Soubise and Hildburghausen into Saxony.

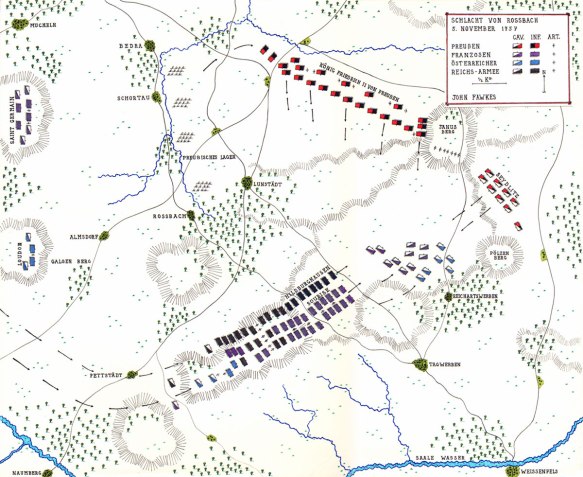

There was some maneuvering west of the Saale before the two armies faced each other at Rossbach, Friedrich’s at the western terminus of a sausage-shaped complex of low eminences, with the Janus and Polzen hills at his rear. The Austrians were moving in Friedrich’s strategic rear, and however slowly they advanced, he was required to do something. He was proposing to attack the enemy camp, a rather desperate undertaking in a completely open plain dotted with villages, when on November 5 they saved him the trouble.

Soubise and Hildburghausen had been reading, and from their documents they learned that the King of Prussia won battles by throwing his full strength against the enemy’s left flank. Now they decided to outdo him by hurling their whole army quite around his left and rear to take the hills there and cut his communications. They formed with their cavalry in the vanguard, the infantry in three columns behind, and began a wide sweep around the Prussian left through the village of Pettstädt, with their trumpets blowing.

There were only three defects in this plan. One was that the plain was completely open, and Friedrich had an officer on the roof of the highest building in Rossbach who could observe every move; the second was that the tracks were both sandy and muddy, and the march slow; and the third was that the moving column, in some witless idea of gaining surprise, threw out no scouts or cavalry screen. When word was brought to the king that the enemy had swung through Pettstädt, he calmly finished his dinner, then at the double-quick took up an entirely new disposition. Seydlitz, with all the cavalry, was posted out of sight behind the Polzen hill, with a couple of hussars as pickets atop; the artillery on the reverse slope of Janus, only the muzzles projecting; the infantry behind the guns, most of them rightward. The beginning of the movement and the apparent disappearance of the Prussian force were observed from the allied army; they assumed that Friedrich was retreating, and ordered hurry to catch him.

As they sped up, at three-thirty in the afternoon, Seydlitz came over Polzen Hill with 4,000 cavalry, “compact as a wall and with incredible speed.” He hit the allied horse vanguard in flank and undeployed; rode right through them, overturned them utterly, and drove what was left from the field. Seydlitz followed till the rout was complete; then sounded a recall and formed in a dip of ground at Tagweben, behind the enemy right rear. The moment their field of fire was cleared the Prussian guns opened on the hapless allied columns, tearing down whole ranks, and as they strove to deploy, Friedrich’s infantry came over Janus Hill, all in line and firing like clockwork. As the writhing columns tried to fall back, tried to get their rear battalions in formation, Seydlitz came out of his hollow and charged them from the rear. It was one of the briefest great battles of record; by four-thirty the allied army was a panic-stricken mob, having lost 3,000 killed and wounded, 5,000 prisoners, and sixty-seven guns. The Prussian losses were 541.

Worst of all for the allies, what was left of their army was so broken that it could never be assembled again. Rossbach was decisive in the sense that it took France out of the war against Friedrich; he had no more fighting to do against the French except by deputy in Hannover. He had cracked the circle of enemies; and he had also achieved a focus for German nationalism and assured the support of England. After the battle Parliament increased his subsidy almost tenfold.

But there was still almost too much for any one man and any one army to do. While Friedrich was eliminating the imperial and French armies from the war, Austria had slowly rolled up all of southern Silesia, beaten the Prussian forces there in battle, and taken Breslau and Schweidnitz, with their huge, carefully assembled magazines. Friedrich turned over command of the beaten army to Ziethen, a thick-lipped ugly little man; picked up his forces at Parchwitz, and hurried forward to offer the Austrians battle.

He now had 36,000 men and 167 guns, of which one big battery was superheavy pieces brought from the fortress of Glogau. Prince Charles and Daun had nearly 80,000. The latter had expected winter quarters, but the news of Friedrich’s approach drew him out of Breslau into a position in double line. The right was under General Lucchesi, resting on the village of Nippern, behind a wood and some bogs, the center at Leuthen village, the left on Sagschütz. The tips of both wings were somewhat drawn back, and General Nadasti, who commanded the left, covered his position with abbates. Forward in the village of Borne was a cavalry detachment under the Saxon General Nostitz, but most of the cavalry were in reserve behind the center.

It may have been that Friedrich had some doubts about the morale of the beaten army Ziethen now commanded; if so, they were dispelled on the freezing dark night of December 4, when he rode through the camp and all the soldiers hailed him with, “Good night, Fritz.” He assembled his generals and told them that what he intended to do was against all the rules of war, but he was going to beat the enemy “or perish before his batteries,” then gave orders for an advance at dawn.

It struck Nostitz and his detachment through a light mist. Ziethen charged the Saxons furiously, front and flank, made most of the men prisoners, and drove the rest in on Lucchesi’s wing. There was a halt while the mist burned away and Friedrich surveyed the hostile line. He knew the area well, having maneuvered there frequently; rightward from Borne there was a fold of ground that would conceal movement, and he immediately planned to do what the allies had attempted on him at Rossbach–throw his entire army on the enemy left wing. As a preliminary, the cavalry of the vanguard were put in to follow up the Nostitz wreck in the opposite direction. This feint worked; Lucchesi, who like Soubise and Hildburghausen, knew of Friedrich’s penchant for flank attacks, imagined he was about to receive a heavy one and appealed for reinforcement. Prince Charles sent him the reserve cavalry from the center and some of that from the left.

But the storm died down there, and to Charles and Daun, standing near the center, it seemed that this must have been a flurry to cover the retreat of inferior force, for Friedrich’s army had passed out of sight. “The Prussians are packing off,” remarked Daun. “Don’t disturb them!” There is no record of his further conversation down to the moment a little after noon, when Friedrich’s head of column poked its nose from behind the fold of ground and the whole array of horse, foot, and artillery did a left wheel and came rolling down on Nadasti’s flank at an angle of maybe 75 degrees.

Nadasti, a reasonably good battle captain, charged in at once with what cavalry he had, and succeeded in throwing Ziethen back, but came up against infantry behind, and was badly broken. One can picture the hurry, confusion, and shouting as his whole wing, taken in enfilade by the Prussian volleys, went to pieces. But there were so many of these Austrians that they began to build up a defense around the mills and ditches of Leuthen, and especially its churchyard, which had stone walls. Prince Charles fed in battalions as fast as he could draw them from any point whatever; in places the Austrians were twenty ranks deep, and the fighting was very furious. The new line was almost at right angles to the old and badly bunched at the center, but still a line, heavily manned and pretty solid.

Friedrich had to put in his last infantry reserves, and even so was held. But he got his superheavy guns onto the rise that had concealed his first movement, they enfiladed the new Austrian right wing and it began to go. At this juncture Lucchesi reached the spot from his former station. He saw that the Prussian infantry left was bare and ordered a charge. But Friedrich had foreseen exactly this. The cavalry of his own left wing, under General Driesen, was concealed behind the heavy battery, and as Lucchesi came forward at the trot, he was charged front, flank, and rear, all at once. It was like Seydlitz’s charge at Rossbach; Lucchesi himself was killed and his men scattered as though by some kind of human explosion, while Driesen wheeled in on the Austrian infantry flank and rear around Leuthen. Under the December twilight what was left of them were running.