In December 1939, the U.S. military established an Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) using radar to defend American territory. It employed the SCR-270 radar, the first United States long-range search radar created at the Signal Corps laboratories at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, circa 1937. The radar’s operating frequency was 106 megahertz and it had a maximum range of 150 miles, or greater if the equipment was at an elevated site.

Under the command of Col. Wilfred H. Tetley the AWS established six mobile radar detector sites on O’ahu at Kawaiola, Wainaae, Ka’a’awa, Koko Head, Schofield Barracks, and Fort Shafter. On Thanksgiving Day in 1941, the Schofield Barracks radar set was moved to the Opana Radar Site, a location 532 feet above sea level with an unobstructed view of the Pacific Ocean. The set comprised four trucks carrying the transmitter, modulator, water cooler, receiver, oscilloscope, operator, generator and antenna.

On December 7, 1941, the Opana Radar Site was manned by Private Joseph L. Lockard and Private George Elliot, who detected approaching aircraft at 7:02 am (past the end of the site’s scheduled operating day). Since the truck to take them to breakfast was late, the pair continued to practice with the radar equipment.

The men reported their findings to the temporary information center at Fort Shafter. Pvt Joseph McDonald took the call. Private McDonald found Lt Kermit Tyler when he entered the plotting room when he timed the message. Tyler told him that it was nothing. McDonald called back the Opana Radar site and spoke to Pvt Joseph Lockard. Lockard was excited , he had never seen so many planes.Infected with Lockard’s excitement, McDonald returned to Tyler. McDonald suggested to Tyler to call back the plotters and notify Wheeler Field of the sighting. When Tyler again indicated that it was nothing , McDonald insisted that Tyler talk to Lockard.The information center staff had gone to breakfast and Lt. Kermit Tyler received the report. Tyler reasoned that the activity was a flight of Army B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, and advised the radar crew not to worry. Tyler told investigators that a friend in the Bomber group advised him that whenever the radio station played Hawaiian music all night, a flight from the mainland was arriving, and using that for navigation homing.McDonald was relieved at about 7:40 and returned to his tent waking his tent mate up by saying “Shim the Japs are coming”.Elliot and Lockard continued plotting the incoming planes until 7:40 when contact was lost. Shortly before 8:00 am they headed to Kawailoa for breakfast and only learned about the attack when they arrived. Elliot and Lockard rushed back to Opana and operated the radar until the attack ended.

In the dark of night Kido Butai, a flock of knife-edged hulls cutting through troubled seas, turned their bows south and worked up to 24 knots. They would make their final run to the launch point sheltered by darkness and unseen by enemy patrols.

This night was the culmination of a massive movement. Over 90% of the Japanese fleet was underway, positioning for attacks spread over a 6,000 nm front. The movement of ships directed against Pearl Harbor had begun as early as 11 November, when nine long-range submarines departed the Empire from Saeki Bay en route a refueling stop at Kwajalein, then on to Hawaiian waters. Now, 23 Japanese fleet submarines, five of which carried midget submarines clamped to their decks, patrolled the waters around Oahu, performed reconnaissance, and awaited the air strike, expecting an opportunity to sink the remnants of the American Pacific Fleet as it bolted out of Pearl Harbor to escape the aviators’ bombs.

To the submariners, not the aviators, was given the honor of making the initial moves in the actual attack.

Midget Submarines

Japan’s midget submarines, commanded by young officers none more senior than lieutenant, were released from their transport submarines in the hours of darkness before the aviators’ attack. They attempted first to find and then to penetrate past the submarine net guarding the entrance to the harbor.

One or more were detected outside the harbor by patrolling destroyers and aircraft. One submarine, surprisingly, did make it past the entrance, only to be detected inside the harbor during the attack. It fired its torpedoes at a tender and a destroyer. Both missed and exploded against the shore. The destroyer Monaghan rammed and sank the submarine.

Three of the submarines definitely did not penetrate the harbor. One was sunk by the destroyer Ward a few hours before the arrival of the bombers. The surprise of the main Japanese attack was saved by a small miracle of US Navy bureaucratic indecisiveness. Blending into the background “noise” of the many false alarms and submarine alerts of the previous weeks, the new warning was not assessed as anything particularly unusual or threatening. Instead of issuing an alert, an order was sent for the stand-by destroyer to sortie.

Considering that a submarine had been detected trying to enter the harbor, and considering the history of the British battleship Royal Oak (which was sunk in October 1939 by a German submarine that penetrated into Scapa Flow), the harbor should have been placed on alert to a submarine threat. All ships should have been required to set material condition Zed, their maximum state of watertight integrity (today called material condition Zebra). Had Zed been set before the bombers arrived, California would have remained afloat and Oklahoma might not have capsized.

Two submarines ran out of battery power and did not deliver any attacks. Both were eventually discovered by the Americans with their torpedoes aboard. One was found beached off Bellows Field, the second 15 years later in a small cove.

The attack by the midget submarines could be seen as an allegory for the entire concept, execution, and spirituality of the attack. A flawed strategic concept was executed with incredibly bravery by men who certainly knew that the odds of their success was slim; warning that should have giving the defenders sufficient time to man their defenses and prepare their ships for attack instead became another instantiation of Yamamoto’s life-long string of incredible good fortune. The fleet and its defenders continued to sleep.

Reconnaissance

Yoshikawa Takeo, the Japanese intelligence officer working out of Japan’s Pearl Harbor legation, kept a stream of information on its way to Kido Butai. The striking force received intelligence communiqués on 3, 4, and 7 December (Tokyo time) updating the situation through 6 December. He reported that no balloons or torpedo defense nets were protecting the battleships. In a message received on 4 December, six battleships, eleven cruisers, and one aircraft carrier were in harbor. Updates reported the departure of Lexington. The day before the strike, the Naval General Staff transmitted to Nagumo that the harbor contained nine battleships, three light cruisers and seventeen destroyers, with four light cruisers and three destroyers in drydock. There were no carriers in port, but that disappointment was balanced by the information that the US military on Oahu was not in any unusual state of alert.

As Kido Butai steamed south at high speed en route to the launch point, the fleet submarine I-72 nosed into Lahaina Roads off Maui. She transmitted, “The enemy is not in Lahaina anchorage.”

In the pre-dawn darkness, the cruisers Chikuma and Tone launched reconnaissance floatplanes. One headed to Lahaina Roads and one to Pearl Harbor, scheduled to arrive after first light.

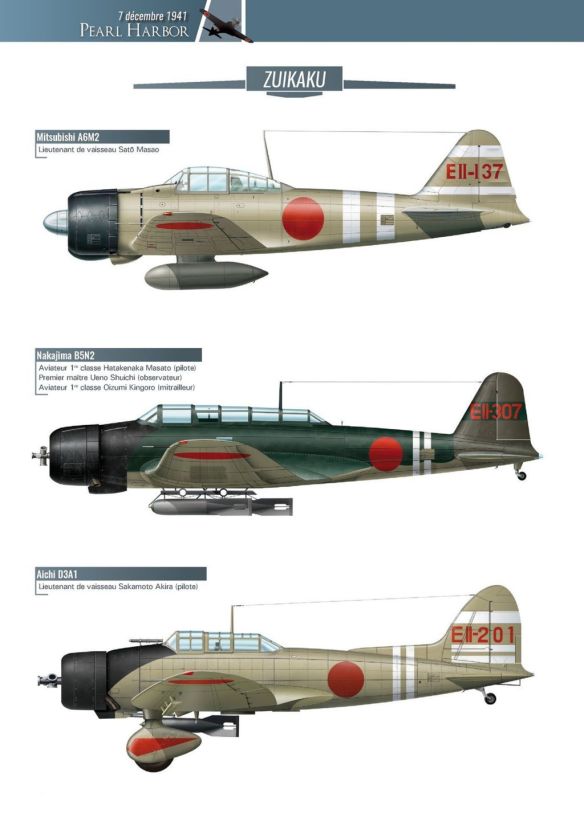

The first wave was launched. Of the 189 total aircraft planned, there were 6 aborts: one B5N Kate carrying an AP bomb, three D3A Vals, and two A6M Zeros. One hundred and eighty-three aircraft executed the attack.

Chikuma’s scout radioed that nine battleships, one heavy cruiser and six light cruisers were in the harbor, and excellent weather conditions existed for the attack. No carriers were observed. This information was received before the second wave was launched. It is not known if the message was copied by the first-wave aircraft; Fuchida, the strike commander, does not mention it in his accounts of the attack.

Due to remarkably speedy aircraft handling, the second wave was ready 15 minutes ahead of schedule. With the first wave still north of Oahu, the second wave launched. One A6M Zero and three D3A Vals aborted. One hundred and sixty-seven aircraft formed for the attack, of which 78 were D3A Vals allocated to go against warships.

As they droned on their nervous course to Pearl Harbor, the aircrews watched a spectacular sunrise, prophetically similar in appearance to Japan’s national symbol, radiating beams from a rising sun, an apparent mark of favor of the gods that raised the spirits of many of the approaching aviators. With careful tuning they could pick up an Oahu radio station playing Hawaiian music, welcoming visitors to the islands. The radio station provided a local weather forecast: visibility clear, a steady tropical breeze out of the northeast, and a heavy cloud layer floating in at 3,500 feet.

Transit

Fuchida claimed that the torpedo bombers were to attack “at almost the same instant.” As Gordon Prange related:

According to this scheme, on receiving Fuchida’s deployment order, Murata would lead his planes in a sweep over the western side of Oahu. Just as they reached a point almost due west of Pearl Harbor, they would divide into two sections and strike the target from two directions at once.

This statement is very deceptive. It implies that the movement down the western side of Oahu was planned, and that the point where the torpedo bombers would separate into two groups was planned to occur west of Pearl Harbor.

The planned route was actually down the center of the island, not “the western side of Oahu.” The separation of the torpedo bombers into two groups was also logically planned to occur north of Pearl Harbor, so as the two groups swung around to attack from the east and the west each would have to travel approximately the same distance to reach their attack IP, allowing for a “nearly simultaneous” attack.

However, upon landfall, Fuchida noted heavy clouds over the Ko’olau Mountains. He decided to skirt the cloud bank, turning the formation to fly in clear air down the western coast. Fuchida’s statement about reaching a point “due west of Pearl Harbor” reflected what actually occurred and not what was planned.

Fuchida’s chosen track effectively eliminated any possibility that the two torpedo bomber groups would attack simultaneously. The Battleship Row attackers would now have to fly south of the harbor, turn east over the ocean, turn inland, and skirt Hickam Field before reaching their IP for the turn to their attack course, while those attacking the carrier moorings would have a straight run in to their targets. Battleship Row would have perhaps five minutes advance warning before Akagi’s and Kaga’s torpedo bombers were in position to attack.

This problem had not been anticipated by the planners. There was no provision to coordinate the two attacks in the event that a different approach course was required. Evidently Fuchida did not see this as a problem, as he took no action as Strike Commander to address it; alternately, he saw the problem, but did not have the means to exert any control.

Fuchida’s Fumble with the Flares

Fuchida was responsible for determining which attack plan would be used and communicating his decision to the attack force, firing one flare for “surprise achieved” or two for “surprise not achieved.” At 0740, off the northwest coast of Oahu, Fuchida made his decision. An account based on interviews with Fuchida related:

Almost sure that the strike would come as a surprise, he fired a single Black Dragon rocket. Murata saw it and swung low toward the target [with his torpedo bombers]. But Lieutenant Masaharu Suginami, a fighter group leader, kept his aircraft in cruise position. Thinking he had missed the first rocket, Fuchida fired another. Then he groaned—Takahashi, mistaking the second rocket for the double signal meaning the enemy was on the alert, swooped in with his dive-bombers. Fuchida ground his teeth in rage. Soon, however, he realized that the error made no practical difference.

Takahashi, the leader of the dive-bomber formation—Fuchida characterized him as “that fool Takahashi, he was a bit soft in the head”—firewalled his throttles and put his nose down, picking up speed. Assuming that it was now his role to immediately attack and distract the enemy defenses, the dive-bombers forged ahead without climbing to their normal bombing altitude. Murata, confronted by this unexpected development, had his torpedo bombers accelerate, trying to get in his attack before the defenses were fully aroused, but his heavily-laden torpedo bombers inexorably were left further and further behind.

Approach

Out of position and at cross purposes, the first-wave formation broke up as the subordinate formations scattered to their assigned targets. There was no attempt to attack the various bases with any simultaneity, and no concern that an attack by one group might prematurely announce the attack to other locations. The attacker’s first shots were fired by a Soryu B5N Kate gunner. Lieutenant Nagai Tsuyoshi, anxious to quicken the attack pace, forged ahead of the Hiryu torpedo bombers and cut across the island, passing so close by Wheeler Field that his gunner cut loose on some parked P-40 fighters.

The Japanese fighters searched the skies for defending fighters. They saw none. Then they looked for anything flying, anything to kill. A US Navy patrol plane spotted the incoming marauders and transmitted a warned, which went unheeded—unable to do more, the aircraft found the clouds and slipped away. But there were other aircraft aloft, mostly civilian pleasure aircraft and private pilot instructors with their students. Some of the more alert fighter pilots recognized these aircraft as a waste of ammunition, but others, anxious for an air-to-air kill befitting a true samurai, broke formation and went for the kills. Several civilian aircraft were shot out of the sky, a few winged away to safety.

The first bombs hit Wheeler at 0751, six minutes before the first torpedo was dropped into Pearl Harbor. The bulk of the defenders’ fighters, modern P-40s and P-36s leavened with obsolete P-26s, were lined up next to the hangars. The base commander had requested permission to keeps the fighters in their revetments, but he was told that would alarm civilians.

Twenty-five D3A Vals hit the base hard. Bombs accurately hit among the lines of densely-packed parked aircraft, smashing many, and igniting tremendous fires fed by aviation gasoline from leaking fuel tanks. Bombs exploded within hangars, which burned gushing dense clouds of smoke. The fire house went up in flames, along with administrative buildings and the Post Exchange. The smoke angled off in the steady breeze, obscuring parts of the flight light and much of the ground facilities, but after the dive bombers’ 550-kg bombs were expended there still were aircraft undamaged, at least 22 that were unobscured by smoke at the upwind end of the fight line. Then, nine A6M Zeros, accompanied by many of the D3A Vals, began to methodically strafe the undamaged aircraft. Wheeler was out of the fight.

Kaneohe was attacked at 0748 (or possibly 0753—in a world without digital clocks absolute precision is not possible). Attempts to warn Bellows and Hickam fields by telephone were disbelieved. Eleven A6M Zeros delivered an eight-minute attack against the base and her 33 PBY-5 patrol planes. The initial slashing attack caused considerable damage and confusion, but the damage was not complete—a movie taken from a second-wave B5N Kate shows many of the PBY-5s by the hangars apparently undamaged. A second wave of level bombers completed the job—in the end, all the American aircraft were either damaged or destroyed.

At Hickam, home of the AAF’s B-17, B-18, and A-20 bombers, nine dive bombers attacked the hangars and administrative buildings while eight others hit the hangars. Nine A6M Zeros strafed the parked planes. Personnel casualties were particularly heavy, with 35 killed when a bomb exploded among the men breakfasting in the mess hall.

As the dive and torpedo bombers approached Pearl Harbor, the fighters that accompanied them peeled off to attack Ewa Marine Corps Air Station, ten miles short of the harbor. Additional fighters, looking for targets for their remaining ammunition before heading for their rallying point, took Ewa as a target of opportunity. By 0815 over two-thirds of Ewa’s aircraft were destroyed or damaged.

The fighters searched for their primary target, enemy defensive fighters in the air. After fifteen minutes of futile search most had given up hope of aerial opposition and instead transitioned into strafing attacks on any reasonable ground target, and some unreasonable ones. While there were some reports of inexpert pilots and inaccurate machine gun attacks, on the aggregate they were highly effective. Considering that many of the bombers were assigned to hit hangars and administrative buildings, it is likely that most of the American aircraft were actually destroyed and damaged by strafing fighters. Inexpert or not, the American aircraft parked in orderly, compact rows were targets that could hardly be missed.

The dive-bombers beat the torpedo bombers to Pearl Harbor. The first bomb was aimed at the southern tip of Ford Island, where there was an amphibious seaplane ramp, an aircraft hangar, and parked aircraft. Various accounts claim that it either destroyed a PBY-5 Catalina seaplane or missed the island entirely. Additional bombs followed, blasting the seaplane and the hangars, and generating a black column of smoke visible for twenty miles. Some ships immediately called away General Quarters. One, still very much in a peacetime mindset, called away their Rescue and Assistance Party thinking that a terrible accident had occurred.

The torpedo bombers were in two groups of two formations each. Murata, commander of Akagi’s air group, led 12 Kaga and 12 Akagi Kates assigned to attack the battleships moored on the east side of Ford Island. Second in overall command was Lieutenant Matsumara Hirata, the torpedo squadron leader off Hiryu, who led eight Soryu and eight Hiryu torpedo bombers against the carrier moorings. As the torpedo bombers approached Oahu, Murata wagged his wings to signal the shift into attack formation.

The two forces separated, with Matsumara flying down the east side of the Waianae Range and Murata down the west side. The Hiryu and Soryu carrier attack planes moved into two strings of eight, while the Akagi and Kaga torpedo bombers tried to form into a single long line of 24 aircraft at 400-meter intervals.

The formation change was poorly executed. Contributing factors were the speed change, the confusion over the flares, and the unplanned location of the formation change, all coupled with the lack of a meaningful rehearsal. Some intervals between aircraft opened out to 1,500 to 1,800 meters, about 25 seconds between aircraft. Followers could not keep track of their leaders, and it was impossible for leaders to exert control over their formations. Some aircraft missed turns and ended up orbiting, searching for their comrades, and falling behind the rest of the attack groups.

The distances prevented communication with hand signals, and radio silence was maintained, even well after it made sense to do so–the Japanese totally ignored the potential of the voice radios that had been installed over the previous year. Japanese aviators later remarked that their radios were unreliable, and considered them of little use. Only the most basic “follow me” leadership was possible in the approach, none for the attack.