On the morning of November 26th 1941, six aircraft carriers of the Imperial Japanese Navy set sail from Northern Japan to the seas to the North West of Hawaii. Their combined payload was 408 aircraft and these comprised the Strike Force intended for the attack on Pearl Harbor. The six carriers were: Akagi, Kaga, Zuikaku, Hiryu, Soryu and Shokaku. Of the 408 aircraft borne by these carriers, 360 were destined for the actual attack while the other 48 were meant to provide defense as Combat Air Patrol (CAP).

The attack was planned in two waves. The first and primary wave carried instructions to attack all the major capital ships of the Pacific Fleet, while the second wave had express intentions to carry out an attack in three tiers. The primary target was aircraft carriers, with cruisers being the secondary targets, and the battleships being the tertiary target. The Japanese military engineers had retrofitted the bombs and aircrafts with modifications that increased their lethal power.

The crews of the Japanese fighter planes were given specific orders to select and hit the targets that were of maximum value. That meant they were to try hitting all the battleships and carriers in the area and then the destroyers and cruisers. The first wave of dive bombers were to concentrate their fire power on the targets on the ground. The fighters in this group were tasked with attacking the airplanes on the airfields by the means of large scale strafing. The intention was to render the American aircraft on the ground as non-airworthy as possible so that an immediate air-defense could not be mounted against the Japanese bombers. The fuel consumption of the aircrafts was a major problem, to deal with it, the aircrafts were given strict orders to return to the carriers and refuel before mounting further attacks.

What was conspicuously absent before the attack was the near absence of reconnaissance aircraft anywhere in the region. The Japanese did not want to take the huge risk of being spotted and drawing attention by way of speculation that they were up to a major mission in the West Pacific. However, shortly before the attack began, two reconnaissance aircraft took flight from the Japanese cruisers Chikuma and Tone. These didn’t fly over Pearl Harbor but went toward Maui and Oahu.

Commander Mitsuo Fuchida was the man associated with leading the main charge of the attack. In the subsequent years to come, he would be hailed as a Japanese hero. He was only later bought down by a group of people that argued that the attack on Pearl Harbor triggered the devastation that resulted in Japan. They believed that if it was not for him, the Japanese would not have had to face the nuclear wrath of the Americans. Commander Mitsuo Fuchida recounted his experience in a published book in 1951. It was originally written in Japanese and sold in Japan only and later was translated to English in 1955. Below is an excerpt from his book.

It was a pleasant Japanese morning. The shores were as aggressive as any average day and the mountains spoke little of the weather. The skies were as clear as Bahamas waters and the sun shone with brightly. Little did the Japanese common folk have any idea that their administrators had been preparing for an assault that would backfire on them in the immediate future. On the other side of the world, the shore of Pearl Harbor looked pleasant from a distance. There was nothing-abnormal going on except the sound of violent waves crashing on the rocks. Lieutenants and Admirals could be seen relaxing on the docks, dressed in uniform, and sipping coffee. They, like the Japanese public, had little idea of what was to come.

Commander Mitsuo recalls vividly the first glimpses of land he and his party sighted. It had been a nervously spent one hundred and forty minutes of flying. There had been little disturbance on the way, having not flown the much longer route of flying over the Asian continent. It had been a wise decision, not to mention an obvious one. Among the scores of pilots that had joined the party, it was their leader, Commander Mitsuo that had the fortune of sighting land. It was the breaking surf of the northern shore of Oahu.

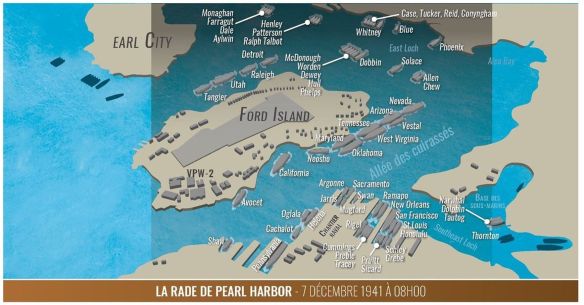

Mitsuo Fuchida and his men peered out of the plane and they saw the Harbor stretching out across the Oahu plain. The skies were clear, with a light mist hanging on the air. Nobody would expect that by the end of the day, widespread devastation would destroy the utter peace that hung quietly overhead. Fuchida and his men took to their work. Through his binoculars, the Japanese bomber counted the eight battleships that were stationed at the harbor, but he found that all the carriers were gone – not a single one remained.

Shortly after this Commander Fuchida received the order to open the attack. Takahashi’s dive-bomber group had already climbed high up into the air, far enough that they were not even visible to those on the ground.

Fuchida and his men made a circuit toward Barbers Point; there was an attack schedule and they had to stick to it. According to the Lieutenant Commander, there were no enemy fighters in sight; not in the air or on the ground. Everything was peaceful, which perhaps, was how the Japanese bombers knew without a doubt that they were going to be successful.

Fuchida further spoke about how the actual attack commenced. Much like a horror movie, the first act of the attack opened with the first bomb falling on Wheeler Field. According to Fuchida, it was followed by a number of dive-bomb attacks that took place on Hickam Field and the bases at Ford Island. Lieutenant Commander Murata had the torpedo bombers and was worried that the smoke released from the attacks would obscure his vision and his ability to hit his targets. He cut his group’s approach short and launched the torpedoes from wherever they were.

From far away, the scene may like beautiful, almost artistic, the waterspouts looking rather majestic and powerful. But there was nothing beautiful about their effects.

The commander then describes in a execution of the most significant event at Pearl Harbor; the bombing and consequent sinking of USS Arizona. Fuchida’s group entered its bombing run towards the eight battleships that were moored to the cast of Ford Island. They were still in the plane. When they reached an altitude of 3,000 meters, Fuchida ordered the sighting bomber to get into position. They were closing in on the harbor when finally, there was retaliation from the American side.

THE THIRD WAVE THAT NEVER CAME

The Pearl Harbor attack took place in two waves of quick succession. However, many junior Japanese officers, including the captains of five carriers, wanted to launch a third wave of attack. Their intention was to demolish the auxiliary structures of Pearl Harbor such as the fuel storage, officer’s quarters, submarine dock etc.

This group of officers included Genda as well. He believed that in the absence of an outright invasion of Hawaii, the number of air strikes should not be restricted to just two waves. The captains of the other five carriers supported his idea. The only high ranking official who opposed the idea of a third strike was Vice Admiral Nagumo. There were many reasons Nagumo vehemently argued against the proposal of a third strike.

By the end of the second wave of attacks, Japan had almost completely lost its surprise advantage. This was further proved by the numbers of aircrafts that were shot down during the second strike. More than two thirds of the casualties incurred by Japan were during the second wave of attacks. Vice Admiral Nagumo reasoned that mounting a third wave to destroy the auxiliary targets was simply too risky to undertake.

The Japanese knew that the aircraft carriers of the American Pacific Fleet were not in Pearl Harbor, but their location was unknown. Vice Admiral Nagumo was deeply disconcerted by this fact. He wasn’t sure whether the Japanese aircraft carriers were within striking range of the American planes and land based bombers.

One of the biggest causes of apprehension for Nagumo was the time factor. The two waves had taken a considerable amount of time and a third wave of attacks would mean that the fighters flying back to the carriers would have to make the landing at night, which was a huge risk in those times.

Compounding the time factor was the weather. The tropical weather had become much worse than it was in the morning and the Vice Admiral was not really keen on flying the planes and fighters in such inclement weather.

Fuel was also major issue. The fuel levels of the entire task force were alarmingly low and a third wave of attack would consume so much fuel that the logistical setup would be very difficult during the return journey. This meant that the fleet may even have to abandon some vessels on the way back home.

At the base of it all was the conviction that Vice Admiral Nagumo had as to the efficacy of the mission. He believed that the Japanese attack had already achieved what it had set out to do. The Pacific fleet was virtually decapitated in the eyes of the Japanese. Nagumo did not intend to incur any more losses in order to simply land a few more blows when they had already done what they set out to do.

In a conference held after the day of the attack, Vice Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was extremely vocal in supporting and upholding the prudent and judicial decisions taken by Vice Admiral Nagumo. But within a few months, it became obvious that the decision to not attack the docks and oil depots was proving to be fatal to Japan. The United States was able to bounce back due to the low depth of the harbor permitting salvaging of the partly destroyed vessels and the close proximity to the mainland, making rescue of the ships and the men possible.

Once this was discovered, Vice Admiral Nagumo came under heavy criticism by Yamamoto himself who specifically stated that the decision by Nagumo to not order a third strike was a completely flawed one.

The immediate collateral of this war for Japan was the death of 55 Japanese airmen and 9 submariners. 29 aircraft were lost to American fire while 74 were damaged.

But the real repercussion, came later when the United States decided to retaliate and declared war on Japan.