General Sir William Slim commented that ‘Burma was last on the priority list for aircraft, as everything else, and in December 1941 the air forces in Burma were almost negligible’. When the new Air Officer Commanding, Burma, Air Vice-Marshal D. E Stevenson, reached Rangoon on 1 January 1942 he found that he had only 21 P40 Tomahawk fighters and 16 Buffaloes under his command. Eventually, after much pressure, he was given 67 squadrons of Buffaloes, three squadrons of Hurricanes, many obsolete, and an American Volunteer Group, supplied with Tomahawks, under Major (later General) Claire Chennault. Stevenson’s Command lacked adequate parts, proper repair facilities and effective anti-aircraft defences. Vigorous efforts were made by this relatively small air force to support the British Army in its retreat from Burma, inflicting severe losses on the Japanese Air Force before the fall of Rangoon on 6 March 1942. This victory enabled the British to evacuate Rangoon without substantial Japanese air interference. However, the Japanese Air Force soon rallied and destroyed the bulk of the RAF on the ground at Magwe air base. What was left of the RAF was withdrawn to India. By the end of May 1942 Burma had fallen to the Japanese.

Apart from one disastrous excursion into Arakan in early 1944 British forces remained on the defensive in Assam while the British and US leaders argued about future strategy in the theatre. Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff wanted to bypass Burma altogether and produced interminable operational plans designed to recapture Singapore using amphibious forces to capture islands in the region, such as Sumatra, as a preliminary to the main assault. These plans were impractical and over-ambitious and they were finally abandoned when it became clear that no landing craft could be spared from North Africa or later from Overlord. Furthermore the US Joint Chiefs, supported by Chiang Kaishek and Stilwell, demanded that the British launch a major offensive to clear North Burma of the Japanese and reopen the Burma Road from Burma into China. Since the United States controlled the aircraft and the resources which were essential if the British were to embark successfully on any campaign in the theatre, the British had to give way. At the Quebec Conference in August 1943 the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, persuaded the United States to agree to the formation of a new Supreme Command for South-East Asia which would be separate from India Command. Churchill had no confidence in Wavell’s military abilities, especially after Wavell’s attempt to recapture the Akyab airfields on the Arakan coast earlier in the year had been repulsed with heavy losses. In fact Wavell himself had suggested earlier in 1943 that the Command be split as the existing theatre was too large for one overworked and tired man to cope with, especially given internal unrest in India and a serious famine in Bengal in 1943, both of which overtaxed the depleted air and ground forces in his Command. After various candidates had been suggested for the new Command—including Orde Wingate—Churchill appointed the relatively young (43) and energetic Lord Louis Mountbatten as Supreme Commander, South- East Asia Command. Mountbatten had been head of Combined Operations in England and Churchill was very impressed with his abilities, even though little in the way of Combined Operations had actually been carried out and the one that was—the assault on Dieppe—had been a disaster. 9 Mountbatten took up his new post in New Delhi in November 1943. Before his arrival British forces had faced defeat after defeat, and the only success, at least in helping to raise British morale, had been Operation Longcloth between February and May 1943, when British long- range penetration groups (the Chindits) led by Colonel Orde Wingate, penetrated deep into Burma in an attempt to destroy Japanese lines of communications. While a few rail and road connections were temporarily disrupted, Wingate pioneered the use of air power for his operations. Hitherto the British in Burma had been confined to the roads, which were easily cut and ambushed by the Japanese. Wingate used aircraft to carry his supplies—food, water, mail, mules, jeeps, guns, etc.—to pre-prepared landing fields or drop them by parachute. To further harry the enemy, fighter bombers carried out air strikes on Japanese positions. An RAF wireless section, commanded by Group Captain Robert Thompson, was attached to each of Wingate’s columns to signal suitable dropping zones. Pownall described Wingate as ‘a genius in that he is quite a bit mad’ and also as ‘a thoroughly nasty piece of work’. Louis Allen wrote that Wingate ‘had changed the nature of jungle campaigning for good’. Despite the relative paucity of his achievements, most accounts of his campaign agree that their audacity did a lot to raise British morale during a period of continuous defeats.

Mountbatten and indeed all the military leaders in India had long recognised that the key to the reconquest of Burma was a huge increase in the quantity and quality of British air power in the theatre—fighters, fighter bombers, and reconnaissance aircraft and above all air-supply and cargo-carrying planes. Despite Churchill’s criticisms of the two generals—Auchinleck, he wrote, always demanded ‘even greater force and… prescribe[d] far longer delays’ —Wavell as Commander-in- Chief, India and his successor after 20 June 1943, General Sir Claude Auchinleck, did order the construction of all-weather airfields in Assam, and they provided the infrastructure for Britain’s subsequent victories. The structure of the Allied air forces available to Mountbatten and General Sir William Slim, the Commander-in-Chief of Fourteenth Army, in December 1943 was a complex one. The Allied air forces and the one Dutch squadron in India and Ceylon had been commanded by Sir Richard Peirse since March 1942. He had been Air Officer Commanding, Bomber Command until 1941, Sir Archibald Sinclair, the Secretary of State for Air, wrote to Churchill on 10 December 1941 that ‘Peirse possesses not only recent experience in command, but also has a wide background of war knowledge and high staff experience. He is loyal, able and hard-working, and would be a strong support for C-in-C India.’ He was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of Air Command South- East Asia (ACSEA) on 16 November 1943. Although General Pownall, who had been appointed Mountbatten’s Chief of Staff, thought Peirse ‘definitely stupid’, Mountbatten was sufficiently impressed with Peirse to extend his appointment for six months in April 1944. The Supreme Commander wrote to Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal, the Chief of the British Air Staff, that he was on good terms with Peirse who ‘has never failed to give me unbiased and fearless advice’. In September 1944 General G. E. Stratemeyer, Peirse’s able US deputy, argued for a further extension of Peirse’s appointment—he was ‘a wonderful chap to work for’. However Peirse’s affair with Lady Auchinleck, Sir Claude’s wife, whom Peirse eventually married, was now common knowledge and had led Peirse to neglect his duties. Mountbatten therefore refused a further extension and Peirse and Lady Auchinleck were flown to England on 28 November 1944. He was replaced by Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Air Officer Commanding in Chief Overlord, but, when the latter was killed in an air crash on his way to take up his command on 14 November, his place was taken by Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park on 24 February 1945, an inspiring leader who got on well with Mountbatten and the US personnel.

As Air Commodore Henry Probert has pointed out, Peirse was a somewhat remote and aloof character but ‘he fought interminable battles to win for his command the resources it needed for the Far East war; he led it through the multiplicity of operations… and he contributed most ably to the higher direction of the campaign in South-east Asia’. In 1942 Peirse fought an energetic and ultimately successful battle with the Air Ministry about the reorganisation of his command structure, a reorganisation which the Air Ministry had initially rejected.

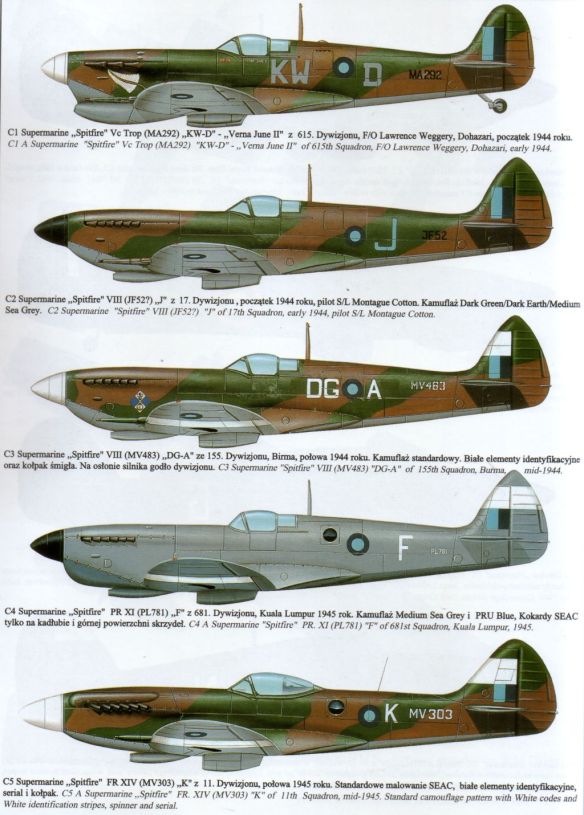

He faced a gloomy situation. In May he informed Portal that ‘Everything in India is unbelievably primitive. The totally inadequate staff and complete lack of things essential is quite devastating, and much of the personnel is past praying for—the Government of India is an Alice in Wonderland hierarchy.’ The air force in India consisted of a collection of obsolescent aircraft and its personnel was demoralised by repeated defeats. Because of India’s inadequate industrial base, new aircraft, airmen, fuel and raw materials had to be imported via the Cape route, and took four months to reach India from Britain and the United States. However, despite enormous transportation problems and a lack of skilled engineers in India, by November 1943 275 airfields had been constructed in the north-east of India. Repair and maintenance facilities were also vastly improved, increasing the serviceability of aircraft to 80 per cent from 40 per cent in March 1942. Signal facilities, reconnaissance and air defences were also upgraded. By October 1943, although Hurricanes still formed the main defence force, high-performance Spitfires Mark VIII began to appear, while A1 Beaufighters were brought in from the Middle East for night fighter defence. Vengeance dive bombers were also used to assault enemy positions in Arakan. The influx of new machines enabled Peirse, in his operational directives to his Command on 12 December 1943 and 21 January 1944, to set out the tasks of the Allied air forces. These were to protect the construction of a new road from Ledo to Myitkyina, which Stilwell’s Chinese forces were in the process of constructing, to secure the air route from Assam to China and drive the Japanese Air Force out of Arakan. 3rd Tactical Air Force was to engage and destroy the enemy aircraft in the air, and attack enemy airfields and installations. Once land operations began, enemy targets in forward areas were to be attacked. Strategic Air Force was tasked with the mission of destroying Japanese shipping, factories, railways and bridges.

However, Dakota transport planes, which Mountbatten and Slim were convinced were the key to future victory, were few in number. Britain depended on the United States for their supply. As early as November 1942 Wavell replied to an urgent request by General Irwin, GOC India, for more air transport planes: ‘I wish I could get you more. They do not appear to be making any at all at home and we are entirely dependent on the Americans, who also appear to be in short supply.’ Pownall lamented in November 1943 that ‘the problem of transport aircraft is a proper nightmare’. He found one full admiral and two full generals ‘sitting round a table to try and screw out three Dakotas from somewhere—anywhere—to fulfil an urgent need’. To make matters worse, 10th USAAF, which controlled most of Burma’s transport aircraft, was not under Mountbatten’s command but was a separate entity, commanded by General G. E. Stratemeyer, USAAF, since August 1943. He was responsible to General Joseph Stilwell, who had been appointed as Mountbatten’s Deputy Commander but was also Chiang Kai-shek’s Chief of Staff, an independent command based in Chungking. Most of 10th USAAF’s transport aircraft were employed in ferrying supplies from India to Chiang’s base in Chungking across ‘the Hump’. The United States Joint Chiefs of Staff insisted on retaining control of all US aircraft in SEAC since they were intended to support the China theatre and not Burma. If Mountbatten wanted to divert planes from the airlift he had to ask the Joint Chiefs for permission through ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell, who was an uncooperative and testy Anglophobe. All that Mountbatten had at his disposal for future campaigns in Burma were six squadrons of USAAF General W. F. Old’s Troop Carrier Command, which had to meet the needs of both India and Burma. One of Mountbatten’s first achievements as Supreme Commander was to persuade the US Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, and General Henry Arnold, the Commanding General of USAAF, at the Sextant Conference in Cairo in December 1943 to agree to the integration of the two air forces under Peirse, with Stratemeyer as his second in command. The integration took place on 12 December, despite strong opposition from Stilwell and Stratemeyer. The unified force became Eastern Air Command with Stratemeyer as its commander and at the time of its formation consisted of 735 aircraft: 464 RAF and 271 USAAF fighters, bombers and reconnaissance planes. The Command had a numerical superiority over the Japanese of about three to one. Mountbatten commented that ‘I absolutely had to integrate… the two Air Forces were running in watertight compartments with friction which occasionally came to a head.’

The newly arrived Spitfires soon demonstrated their superiority over the Japanese Zeros when many Japanese fighters were shot down in an engagement above Chittagong on 31 December 1943 and along the Arakan coast on 15 January 1944. After the arrival in Burma in early 1944 of US long-range P-51 (Mustang) and the P-38 (Lightning) fighters, Allied air supremacy was virtually assured. As a result Slim could now proceed with his planning for an offensive into Burma based on the setting up of strong points where British and Indian troops would remain if attacked by the Japanese and then, once they had defeated the Japanese, would resume their advance. Hitherto the Japanese tactics of encirclement and infiltration had successfully forced British forces to retreat, often in humiliating circumstances. These strong points were to be supplied by air, and Slim ordered his principal administrative staff officer, Major-General A. H. J. Snelling, to reinforce the air-supply units at Agartala and Comilla, intensify the training of the pilots and engage in the day-and-night packing of supplies to be airlifted to General Sir Philip Christison’s XV Corps, which was to spearhead the invasion. To achieve these ends, Snelling worked closely with General Old and his Troop Carrier Command. Christison began his advance to the south in November but on 4 February the Japanese opened up the Ha-go offensive designed to infiltrate, encircle and destroy the British forces in Arakan. This time, contrary to Japanese assumptions, the British did not retreat but held fast to their positions. Nevertheless the outcome of the initial battle of Ngakyedauk Pass in Arakan in early February 1944 was by no means certain. The Japanese deployed 34 fighters and ten bombers over the battlefield and initial Spitfire interception was not very successful. Furthermore attempts to air-supply Messervy’s beleaguered 7th Division (the Battle of the Administrative Box) by 31 Squadron RAF had to be abandoned on 10 February. Seven out of 16 transport aircraft were lost to enemy fighters and light anti-aircraft and small arms fire from enemy-held areas over which the supply-dropping aircraft had to fly as low as 200 feet to reach the dropping zone. For a time air dropping by night had to be resorted to but after 14 February a fall-off in Japanese air activity led to the resumption of air dropping by day. The volume of supplies dropped sustained the besieged garrison until Slim brought up reinforcements and defeated the Japanese on 24 February. In early March Christison was able to resume his offensive towards Akyab.