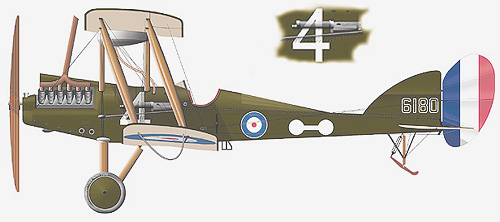

Lt R Watts No. 19 Sqn RFC Image: © R. N. Pearson

In the spring of 1915 before the advent of the Fokker monoplane and its synchronised machine gun, the mainstay of the RFC, the Royal Aircraft Factory’s B.E.2c two-seat reconnaissance machine, was marred only by its low power. As its creators noted, the B.E.2c was often flown solo for photographic or bombing missions and its performance marginally increased when released from the additional weight of an observer. In May, work began on a single-seat version fitted with a more powerful engine that could carry out these essential tasks more effectively.

The prototype, later designated B.E.12, was created by the conversion of a standard production B.E.2c, 1697, which had been built by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company. As originally built, 1697 was an early model powered by a 70-hp V8 Renault engine rather than the 90-hp RAF1a that had superseded it. Also, it was fitted with a twin-skid undercarriage, both of which were removed and returned to the stores as spares during June. The engine mounting was modified to accept the 140-hp V12 RAF4a engine. The increased length eliminated the forward cockpit and was fitted with two small air scoops in tandem with a complex exhaust system that terminated in a single vertical discharge on the engine centreline. A fuel tank, shaped to match the fuselage decking, was fitted behind the engine and a vee undercarriage that was introduced to the B.E.2c was fitted. The wings and tail surfaces remained as originally designed.

Conversion work proceeded through June and July but on the morning of 28 July, the B.E.12 was submitted for final inspection with a request that it should be treated as urgent. Approval was given later the same day and in the evening it making its first flight with Mervyn O’Gorman, the Factory Superintendent, writing to Col. W. S. Brancker, then Director of Air Organisation, as follows:

I have had a preliminary run on B.E.12 today. As I think you know, a Maurice Farman alighted on my speed box on the speed course and smashed it up, but I can say that she is as stable as B.E.2c—alights as slowly—climbs like mad and flies in the neighbourhood of 100 mph. I do not see why pilots who can fly a B.E.2c should not use it as soon as they get it. They can throttle down at first so that it is a B.E.2c and after a few alightings, open up the throttle.

1697 was not as good as O’Gorman initially believed as it remained at Farnborough for further development. Throughout the summer, engineers were largely concerned in adequately cooling the rear cylinders of the V12 engine and by 22 September, it had been fitted with an enlarged fin. The first production order, 87/A/123, for fifty machines (6136–6185) was placed with the Standard Motor Company on 30 September with an order for 200 (6478–6677) placed with the Daimler Company shortly thereafter. Both of these companies were based in Coventry and production was also undertaken by the Coventry Ordnance Works. Production machines differed from the original in having modified engine mountings, a single and larger air scoop above the engine, and the top of the petrol tank was shaped to blend the angle of the scoop into the line of the fuselage decking. Separate exhausts were fitted to each cylinder bank, discharging above the upper wing, and the design reverted to the B.E.2c-style triangular fin originally fitted to 1697. A camera mounting was included as a standard fitting on the starboard side of the fuselage outside the cockpit.

Both Daimler and Siddeley-Deasy Ltd, another Coventry-based company, built the RAF4a engine with the latter company delivering their first completed engine in December 1915 (deliveries from Daimler commenced in February 1916). However, Daimler was the first to deliver a completed B.E.12 with 6478 handed over towards the end of March 1916. It was sent to the Central Flying School for evaluation on 3 April where it was joined by 6479 on 11 May and received the following report:

Stability, lateral and longitudinal, good. Directional bad with small fin. Length of run to unstuck 140 yards. To pull up with engine stopped 230 yards. Machine was not tiring to fly. Lands as easily as B.E.2c. Manoeuvres slower than B.E.2c. Larger fin required.

Meanwhile at Farnborough with the Fokker Scourge on going and with a growing need to arm British aeroplanes, some effort was being made to fit a gun to the B.E.12. However, the air scoop and exhaust were proving a hindrance as the gun could not be fitted in front of the pilot. Also, a further problem was the lack of suitable synchronisation gear. 1697 was therefore first fitted with a Lewis gun, mounted on the portside of the fuselage and with deflector blocks fitted to the propeller to prevent damage. Introduction of the Vickers-Challenger mechanical gear saved the day and allowed a belt-fed Vickers machine gun to be fitted in place of the Lewis. This was mounted on the portside of the fuselage, thus avoiding the engine’s air scoop and also simplified the installation of the mechanical linkage for the synchronisation gear. Sighting was still an issue due to the protruding air scoop and a ring and bead-sight system was therefore fitted on the outside of the port interplane struts. This forced the pilot to lean out into the slipstream to take aim, a far from ideal arrangement, but all that was possible on a machine that had never been designed to be armed.

Tests were also conducted with the Davis gun that inclined upwards for operations against Zeppelins whose raids were creating havoc among the civilian population. This weapon fired a two-lb shell and was made recoilless by ejecting a similar weight of lead shot and grease backwards through an opposed barrel. In turn, this was fired by the same charge and the breech was central between both barrels. Invented in 1910, the Davis gun was a modest success; however, its installation on the B.E.12 was not and the experiment was quickly discontinued.

The B.E.12 first entered service in the home defence role with 6484 joining No. 52 Squadron on 18 May with 6489 going to No. 51 Squadron. 6490 was sent to No. 53 Squadron and others quickly followed.

6479 and 6483 were the first examples to go to France, the latter joining No. 10 Squadron on 31 May and made its first operational sortie as an escort piloted by the squadron’s commanding officer, Major W. Mitchell. When flown as a fighter, its poor manoeuvrability was immediately apparent as was the inherent stability that was part of its design as a reconnaissance machine (inherited from the B.E.2c). At the end of June, Col. H. R. M. Brooke-Popham, the RFC’s Quartermaster, complained that ‘The pilot cannot exert enough force on the elevators to keep the machine’s nose down completely preventing a suitable dive with the engine at full throttle.’ This problem was later resolved by exchanging the tailplane and elevators for the smaller surfaces designed for the B.E.2e. Brooke-Popham also passed on a complaint that the synchronisation gear would not operate the gun if the engine speed fell below 800 rev/min. This happened quite often during manoeuvres and Brooke-Popham suggested that the gear be fitted with a double cam that resolved the problem.

No. 19 Squadron, which had first formed in 1915, was fully equipped with the B.E.12 in June 1916 and flew to France the following month. They arrived at the depot at St Omer on 30 July before flying on to their base at Fienvillers that they were to share with No. 27 Squadron the next day. The B.E.12 was still not an effective fighter and the squadron suffered its first casualty on 13 August when 6349, flying as an escort, was brought down by a German two-seater and captured intact, its pilot, 2 Lt C. Geen, taken prisoner.

No. 21 Squadron, the only other unit to be fully equipped with the B.E.12, converted to the type from the R.E.7 bomber towards the end of August. Although its duties now included defensive patrols, it continued to operate in the bombing role with up to 336-lbs of bombs in racks under the lower wings. In this role, it was sometimes fitted with a rearward-facing Lewis gun mounted on the portside of the fuselage for defence of the tail and sighting the weapon was almost impossible and at least one pilot considered it ‘little more than a joke’. However, on 22 September 1916, Lt G. A. Baker of No. 19 Squadron while flying 6548 shot down an enemy aircraft—one of three victories achieved by the squadron. This was a number that far exceeded those lost due to engine failure or enemy action and two days later, Brig-Gen. Hugh Trenchard, commander of the RFC in France, wrote ‘I have come to the conclusion that the B.E.12 aeroplane is not a fighting machine in any way.’ He requested that no more be sent to France and those already there should be replaced as soon as practicable.

The introduction of the B.E.2e with single-bay wings of unequal span improved the performance of the reconnaissance machine sufficiently and it was logical that wings of the same design should be tried on its descendant, the B.E.12. Designated as the B.E.12a, orders for the new variant were placed with Daimler and the Coventry Ordnance Works, both for fifty machines. Although slightly faster than the original with two-bay wings and considered easier to land when tested at the CFS in May 1917, the RFC in France found it offered no improvement in such essential elements as manoeuvrability and none entered service. Instead, they were assigned to home defence units, training establishments, and to squadrons operating in the Middle East where conditions were considered less demanding than those in France.

In Salonika, No. 47 Squadron received its first B.E.12s in October 1916. The squadron was never equipped with any one type, but like most units in the region, operated a variety of machines, both single and two-seaters. No. 17 Squadron, also operating in Salonika, acquired its first B.E.12s the following month. The idea of sending the B.E.12 to the region seems to have been justified as the type met with some modest success there.

2 Lt C. H. Denning of No. 47 Squadron while flying a B.E.12 managed to bring down an Albatros two-seater on 17 January 1917 that was captured with only slight damage by forces on the ground. Denning shot down another enemy aircraft just two days later. Capt. W. Bell also achieved a number of combat victories flying the B.E.12, including an unidentified enemy aircraft on 24 December 1916 and a Halberstadt fighter on 5 June 1917. Meanwhile, 2 Lt F. D. Travers shot down an Albatros DIII fighter while flying an escort mission on 19 December 1917. Capt. G. W. Murlis-Green of No. 17 Squadron achieved five combat victories flying the B.E.12, including three two-seaters and a seaplane. However, his greatest triumph came on 4 January 1917 when he shot down an Albatros DV fighter that was captured intact.

A single B.E.12 found its way to No. 67 (Aus) Squadron—a unit considered by its personnel to be No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, as which it was later officially recognised—then serving in Palestine and was joined in March 1917 by a number of B.E.12as. The Australians greeted the new arrival with some derision, considering them to be ‘of no practical use’ but, just as typically, did their best with them. On 25 June, while flying as escort to a B.E.2c reconnaissance machine, Lt J. S. Brasell encountered three enemy Fokkers and, although outnumbered and hopelessly outclassed, managed to shoot one down. However, even in the desert, things did not always go so well for the squadron’s B.E.12as and on 8 July, Lt C. H. Vaughn was shot down and killed while escorting a B.E.2e and a Martinsyde when they were attacked by two Albatros fighters.

On 4 August, Lt R. M. Smith was flying B.E.12a, A6329, on a bombing mission near Shario when he encountered two enemy aircraft, forcing down a two-seater before turning on its escort. In the ensuing dogfight, a bullet passed through Smith’s cheeks and destroyed a number of teeth before Smith emerged victorious. During a photographic reconnaissance in B.E.12a, A575, on 17 January 1918, Lt L. T. Taplin was attacked by an Albatros fighter; however, just twenty rounds from his Vickers gun proved sufficient to shoot it down before he calmly returned to his photography.

During February and March 1918, No. 1 Squadron AFC converted to the Bristol F2b and handed its B.E.12as to No. 142 Squadron at its base at Mejdel. As was usual in the Middle East, the squadron operated an assortment of aeroplanes, mostly for bombing and reconnaissance for which the B.E.12 had originally been intended. B.E.12a, 6610, of No. 37 Squadron achieved the type’s most publicised success when on the night of 16/17 June 1917 and piloted by Lt L. P. Watkins, it was credited with the destruction of the Zeppelin raider, L48, which crashed in flames at Holly Tree Farm near Theberton in Suffolk. On landing, Watkins submitted the following report of his attack:

On the morning of June 17th 1917, I was told by Major Hargrave there was a Zeppelin in the vicinity of Harwich and I was ordered to go up in B.E.12, 6610. I climbed to 8,000ft over the aerodrome then struck off in the direction of Harwich still climbing. When at 11,000 ft over Harwich, I saw AA guns firing and several searchlights pointing upwards at the same spot. A minute later, I observed the Zeppelin 2,000 ft above me. After climbing about 500 ft, I fired one drum into its tail but it took no effect. I then climbed to 11,000 ft and fired another drum into its tail without any effect. I then decided to wait until I was at close range before firing another drum. I then climbed steadily until I reached 13,200 ft and was then about 500 ft under the Zeppelin. I fired three bursts of about seven rounds and then the remainder of the drum. The Zepp burst into flames at the tail, the fire running along both sides, then the whole Zepp caught fire and fell burning.

Thousands visited the wreckage and it was widely plundered for souvenirs. It was the last Zeppelin to be brought down over England and Watkins, one of three pilots who had fired at it (the others being Capt. R. H. Saundby who flew a DH2 and Lt Holden and Sgt Ashby in an F.E.2b) were decorated for their efforts.

Despite this success, it had generally been found that the B.E.12 and 12a were unable to climb high enough to reach the latest Zeppelins—which could operate at 20,000 feet—and a number of interceptors were fitted with the 200-hp-geared Hispano-Suiza engine. Being water cooled, this engine did not require the air scoop and so changed the line of the forward fuselage, the fuel tank being fitted reversed so that its sloping top offered less resistance and a frontal radiator introduced. Armament often comprised of two Lewis guns fitted above the upper wing where their muzzle flashes would be out of the pilot’s line of sight and so would not adversely affect his night vision, the sights remaining on the centre-section struts. Instrument lighting was provided as were Holt flare brackets on the lower wings to facilitate landing at night and the exhausts usually ended in flame dampers. The conversion was completed by 25 September 1917 and its performance received a fairly enthusiastic report when tested. Despite demand for the Hispano-Suiza engine (particularly for the S.E.5a and Sopwith Dolphin, examples of which were stored awaiting engines), the rate of climb and ceiling of the new variant, designated B.E.12b, was so improved that 100 were ordered from Daimler for home defence duties. However, the Zeppelin raids were largely over and the new engine could not make the B.E.12 a sufficient match for the Gotha bombers then making daylight raids on England.

A total of 601 examples were built, including a further 200 ordered in 1917 for home defence, an overly large number for an aeroplane that failed to find its ideal role. At the end of the war, the RAF had around sixty B.E.12 and 12as, mostly in the Middle East. It also possessed over 100 B.E.12bs, most either in store or at various depots, but they seem to have been quickly disposed of as the type saw no post-war use either service or civil.