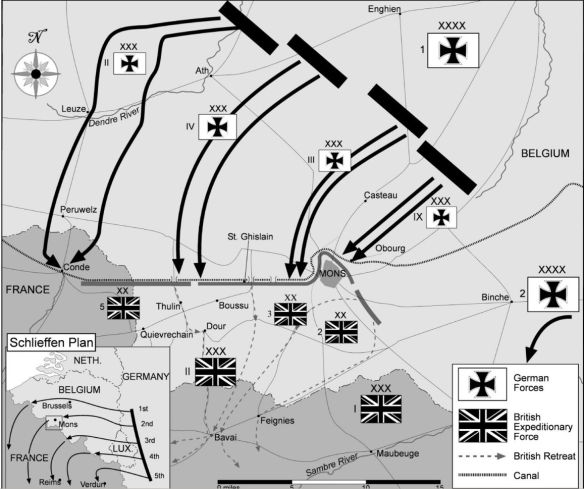

Opposing Forces in the Battle of Mons, 22–23 August 1914

“Defend” is probably the wrong term for the posture of the two divisions under Smith-Dorrien’s command. It is more realistic to say that I Corps’ defensive positions more closely resembled a hasty defense or a security zone with outposts consisting of platoon or company strongpoints. For instance, British infantry battalions created firing positions inside the town of Mons and along the canal, but battalions were by no means entrenched on the scale they would be later in the war. The urban terrain also fragmented the hasty defense. The corps’ disposition, therefore, reflected both the compartmentalized terrain that included houses, farms, and industrial buildings, as well as the limited time Smith-Dorrien and his officers had to select and prepare their positions on 22 August. Compounding these difficulties was the British army practice of issuing written orders, even in the heat of battle, which perilously slowed the decision making cycle at the tactical and operational levels.

According to Smith-Dorrien, II Corps’ artillery was scattered across the countryside in less than ideal positions to effectively engage an attacking enemy. Guns were positioned to optimize direct fire engagements. At this point in the war, the British army had not yet learned how to concentrate and mass the destructive power of indirect fire.

The canal, which runs perfectly straight on an east-west line between Condé and Mons and then loops north and east, dominated II Corps’ operation. In 1914, the canal was on average seven feet deep and sixty-four feet wide—perhaps not deep and wide enough to delay a determined enemy for long, but useful enough in a hasty defense. An order to blow the bridges over the canal along the 5th Division front was issued during the afternoon of 23 August, but all of the bridges (with the exception of the lattice girder bridge over lock number four) in Smith-Dorrien’s sector would not be blown until the morning of 24 August, long after German attacks had penetrated the British lines at several points along the canal.

At 6 a.m., when French met with his corps commanders to provide his operational intent, the German artillery bombardment of the British lines around Mons was already well under way. According to Smith-Dorrien, French “told us be prepared to move forward, or fight where we were, but to get ready for the latter by strengthening our outposts and preparing the bridges over the canal for demolition.”

The word “outpost” most likely did not mean the same thing to Smith-Dorrien as it did to French. French’s use of the word, which in the parlance of the cavalry suggests a temporary occupation, meant that he may have expected Smith-Dorrien to disengage his force after a short fight and retire to subsequent fighting positions. For the infantry, however, “outpost” may have been interpreted as an outlying post without necessarily suggesting temporary occupation in the form of a picket line. To the infantry officers commanding in II Corps, strengthening of the outpost line would force the enemy to deploy much earlier and serve to disrupt any forward move by the enemy without necessarily implying a rapid disengagement and withdrawal. The British experience against the Boers in South Africa, subsequently reinforced in 1905 by reports of the Russo-Japanese War, promoted the idea that a few well-trained British infantrymen, unsupported by artillery in direct fire, could defeat large numbers of attacking forces. Subsequent fighting in the division area would suggest this was the more likely interpretation of French’s instructions.

Fighting on 23 August eventually occurred in and around Mons where Dorrien-Smith had expected it. German cavalry appeared from Obourg in the east and moved toward the bridge facing Ville Pommeroeul in the west on the extreme left flank of II Corps. Contact on II Corps’ left was relatively light. However, in the Mons salient and on Bois la Haut to the southeast, fighting was intense, as Smith-Dorrien anticipated it would be. Whenever the German artillery stopped firing, German troops assembled to storm the British positions. At first, British rifle fire drove the Germans back to their starting positions. The Germans quickly reorganized and repeated the attempt, normally on a new line of attack, only to be driven back yet again.

Accurate British rifle fire definitely made a difference. The British army’s prewar training program emphasized and rewarded rapid, accurate fire. Translated into action, the average British soldier was reportedly able to hit a man-sized target fifteen times a minute at a range of at least three hundred yards with his Lee-Enfield rifle. It may also be the case that in the early phase of the Battle of Mons, the attacking German troops were more densely packed so they could communicate in new and unfamiliar terrain. Yet it is worth noting that when the hasty attacks failed, the Germans rapidly adjusted their tactics.

The German army employed aircraft with a tactical system of colored smoke signals to identify and mark targets. German aircraft soon arrived overhead, and the appearance of colored smoke nearby scattered the British defenders. Accurate, devastating artillery fire followed. Like the British army, the German army also trained for mobile warfare, but the Germans viewed firepower, particularly artillery fire, as the real key to mobility in battle.

Thirty to forty minutes after the first hasty attacks failed, the German guns reengaged the British lines with greater precision and ferocity. Infantry reinforcements arrived, and the German attacks recommenced. This time, when the guns ceased firing, the German infantry moved forward in rushes supported by machine gun fire until they either overwhelmed the British defenders or discovered the British had withdrawn to new positions.

These methodical and determined German attacks through the streets and alleys of Mons utilized artillery in direct fire to obliterate British positions, especially machine gun positions, inside buildings or behind barricades and sandbags. Given the inability of the British defenders to effectively employ their own artillery in the dense, urban terrain, the British infantry could not withstand these tactics for long.

British infantry fought back against the German attacks in and around Mons’ houses and slag heaps. Losses on both sides were heavy. By noon, however, only six hours after the German guns began firing, nearly two German divisions had advanced to the canal in brutal house-to-house fighting. By early afternoon on 23 August, German troops crossed the canal at Jemappes, an action that made 3rd Division’s defensive line in the Mons salient untenable. In several places along the front, the Germans were already south of the canal.

While the German 18th Division attacked the Mons salient, the 17th Division had pushed forward, crossing the undefended canal to the right of the Middlesex Regiment. As the German infantry swung round towards Mons, they threatened the exposed right flank of the 3rd British Division. The 1st Gordon Highlanders and 2nd Royal Scots who protected the right flank were stretched thinly over 4 miles, angled back toward I Corps and facing the villages of St. Symphoien and Villers St. Ghislain.

Given the weight of the German attack and the effectiveness of German tactics, by 1 p.m. on 23 August, the British were holding on by their fingernails. In fighting at the Nimy bridge in the center of the Mons salient, British lieutenant Maurice Dease of the Northumberland Fusiliers took control of the machine gun on the bridge after everyone in his section had been killed or wounded. Dease continued to fire despite receiving several mortal wounds by German gunfire. Another British fusilier, Private Sidney Godley, ran forward to man the fusiliers’ last operational machine gun, but he was eventually overrun and captured by attacking German troops. Both men were awarded Victoria Crosses.

In a phenomenal act of courage, German private August Niemeyer swam across the canal under intense British fire and brought back a boat so that his patrol could cross. The German patrol then crossed the canal and engaged the defending British soldiers. Then, Niemeyer set the swing mechanism in motion that moved the bridge back into position across the canal and reopened the bridge to road traffic. In its closed position, the Nimy swing bridge allowed traffic to cross the canal. When a water vessel needed to pass, motors rotated the bridge horizontally about its pivot point out of the way. The British troops rotated the Nimy bridge away from the banks but did not disable the mechanism. As a result, even after Niemeyer was killed, German troops were able to charge across and secure the bridge. By 1:40 p.m., the British infantry was falling back under fire from the Germans advancing through Mons to Ciply. Had the machine guns been placed at an angle in a protected position from which they could have swept the bridge, the British might have held it much longer.

But more important, the order from Smith-Dorrien left the decision to his subordinate commanders regarding when the bridges and boats within their zones should be blown. Though by no means atypical for British commanders, Smith-Dorrien’s rather casual approach to the matter made the early loss of the canal to the attacking Germans a virtual certainty. At 3 p.m., Smith-Dorrien decided it was time to withdraw his force to new defensive positions. He ordered the hard-pressed 3rd Division to leave the salient and fall back to positions just south of Mons. The 3rd Division’s move necessitated a similar retirement by the 5th Division. Before midnight on 23 August, both divisions of II Corps were in a hasty defense along a line running through the villages of Montroeul, Boussu, Wasmes, Pâturages, and Frameries.

Around 7 p.m. on 23 August, the situation on Smith-Dorrien’s right in and around Mons was serious enough for Smith-Dorrien to ask Haig for assistance. As Haig’s troops had hardly been engaged at all (I Corps sustained only forty casualties), Haig agreed to send his 5th Infantry Brigade to plug the growing gap in Smith-Dorrien’s right flank. Fortunately, II Corps’ 9th Infantry Brigade managed to restore the line before I Corps’ assistance was needed, but the renewed German attack on II Corps’ right signaled real danger. Three German infantry divisions were reportedly assembling for a major attack on 24 August.

Smith-Dorrien and his 3rd Division commander, Major General Hubert Hamilton, did not know it, but farther to the east units of the German IX Corps were also crossing the canal in force, threatening to drive a wedge between the BEF and the French. The withdrawal of the French Fifth Army left the BEF’s right flank wide open. What no one in the BEF knew was that all 4 French armies, not just the Fifth, were in a headlong retreat to the west. The French armies’ combined strength had been reduced by 200,000 casualties, including 75,000 dead. A German soldier who witnessed the French retreat described the scene:

When we reached the ridge of those heights (above the Meuse) we were able to witness a horrifying sight with our naked eyes. The roads which the retreating enemy was using could be easily surveyed. In close marching formations the French were drawing off. The heaviest of our artillery was pounding the retreating columns, and shell after shell after shell fell among the French infantry and other troops. Hundreds of French soldiers were literally torn to pieces. One could see the bodies and limbs being tossed in the air and being caught in the trees bordering the roads.

Even with I Corp’s assistance on the right flank, by nightfall all of Smith-Dorrien’s infantry battalions were still retiring under pressure from advancing German troops. Smith-Dorrien had no corps reserve of sufficient strength to counter a German breakthrough anywhere along the II Corps front. Without a timely and rapid withdrawal under the cover of darkness, the 3rd Division might not survive at all. At midnight on 23 August, Smith-Dorrien waited impatiently for new instructions from the BEF commander.

Though Smith-Dorrien was not aware of it, Sir John French had decided at 11 p.m. on 23 August to completely withdraw the BEF to a line based on the town of Bavai. The reason for the delay in the receipt of French’s order to Smith-Dorrien was that it had to be delivered by car driven in the dark over a distance of twenty-five miles. Thanks to landline communications with BEF General Headquarters (GHQ) at Le Cateau, Haig received the order at least three hours earlier and began disengaging his corps from its positions at 2 o’clock in the morning. Smith-Dorrien did not receive the order until dawn on 24 August, but he had reached the same conclusion much earlier in the day.

To the astonishment of both corps commanders, French left the planning and execution of the withdrawal entirely in their hands. Complicating matters, French commander in chief General Joseph Joffre directed French to keep the BEF west of the fortress of Maubeuge, restricting the number of roads available to the BEF. The BEF’s retreat was just beginning—it would last for 2 weeks and cover more than 250 miles.

Smith-Dorrien did not wait for orders. He drove straight to Haig’s command post and obtained Haig’s agreement that I Corps would cover the retirement of the 3rd Division as it moved toward Sars-la-Bruyere. When 3rd Division began its withdrawal, Smith-Dorrien notified Haig that the 5th Division would displace to a new line running from Blaugies to Montignies-sur-Roc.

French’s decision to hold the line at Mons for 24 hours had achieved the aim of slowing the German advance, but losses in II Corps, particularly in the 3rd Division, were heavy. Total British casualties at Mons were 1,638 men killed or wounded. German losses were between 1,900 and 2,000, but of course, the Germans were attacking. The British infantry performed beyond expectation against a much larger, more lethal German force. But the success was temporary. In the failing light of the early evening, German engineers were erecting pontoon bridges where the existing bridges had been destroyed. The German attack continued westward, wheeling around Smith-Dorrien’s troops “like a closing door hinged on Mons itself.”

Von Kluck described his feelings about the fight for Mons: “After the severe opposition offered by the British Army in the two days’ battle of Mons–St. Ghislain, a further and even stronger defence of Valenciennes-Bavai-Maubeuge was expected.” The BEF’s successful disengagement from Mons meant the First Army commander would pursue the BEF, drawing the First Army farther away from the original and more dangerous axis of its westward advance to the north of Paris.