In 479 or 477 BC the Veientanes overwhelmed the Fabii and slaughtered them almost to a man.

A Roman citizen in weapons (in the fifth century BC). He has a bronze helmet, round shield (Clipeus), spear and a short sword. The army at this time consisted of wealthy nobles, able to buy this expensive equipment.

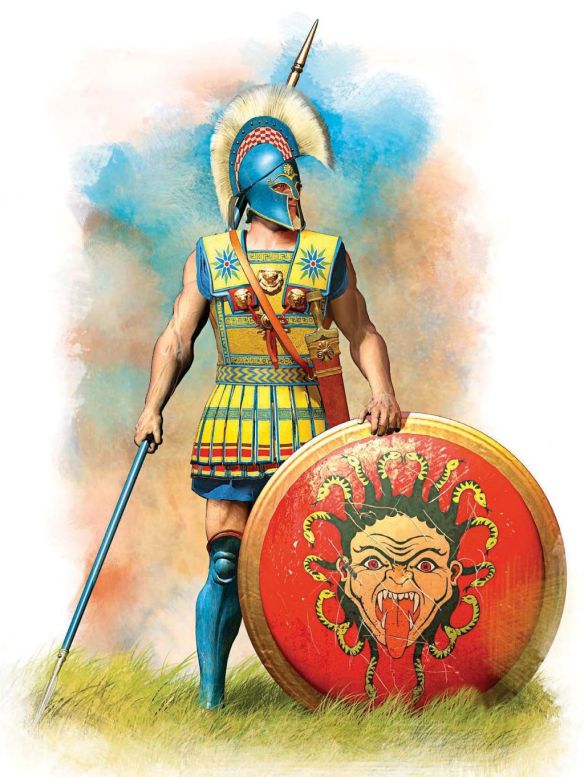

An Etruscan officer second class of the fifth century BC. He is distinguished by the type of the conical helmet decoration, similar to that the hoplites. His shield is reinforced with skin. His weapons are a spear and falcata sword.

477 B.C. CREMERA

While supplying her fair share of troops for the wars against the Volsci and Aequi, Rome received little, if any, aid from her allies in the war against Veii, the most southerly of the Etruscan cities. Located 10 miles to the north of Rome on a rocky eminence, Veii ruled over a large and fertile territory and could thus support a substantial population and from that recruit a powerful army. Much of her wealth stemmed from industry and trade and because of this, as well as any ambitions for territorial expansion, it was critical that she dominated one of the Tiber crossings. Her access to the Tyrrhenian coast, and the lucrative salt pans at the mouth of the Tiber, was blocked by the strip of the ager Romanus that occupied the Etruscan bank of the Tiber, as well as the territory of the unfriendly Etruscan city of Caere. A road, the Via Veientanus, led directly from Veii to the river crossing at Rome, but that route meant Roman control over Veientane commerce and communications. However, Veii was perfectly placed to dominate another of the major Tiber crossings. The valley of the small Cremera River provided a direct route from Veii down to the Tiber and the crossing controlled by the small city-state of Fidenae, only 5 miles upstream from Rome (on the left, or Latin, bank). Fidenae, despite being Latin, thus became Veii’s bridgehead, and from there her goods could completely bypass Rome, following the Anio and the route through eastern Latium down to the Greek and Sabellian markets of Campania and southern Italy.

As we have seen, in 504 BC the Sabine chief Attus Clausus, hard-pressed by his Sabine rivals, migrated with his gentilical band to Rome. Clausus was welcomed by the Senate and adlected into the select patrician order. His name was Latinized and he was known from then on as Appius Claudius. The members of his large clan/war band were granted Roman citizenship and formed the new gens of the Claudii. They were settled above the Anio and acted as a buffer against Sabine incursions. The Sabines are presented in the sources as Rome’s most dangerous enemies at the close of the sixth century BC, and they remained a menace until the middle of the fifth century, occasionally raiding the outskirts of Rome or inflicting a defeat on a Roman army in pitched battle, for example at Eretum in 449 BC. In 460 BC another Sabine, Appius Herdonius, occupied the Capitol in a night attack and attempted to take over the city, but was defeated and killed by the Romans and a force from Tusculum (a rare instance of a Latin city aiding Rome against an opponent other than the Volsci or Aequi). Rather than being identified as a foreign invader, Herdonius was probably a leading Roman of Sabine descent, and the force with which he attempted his coup was a gentilical war band reinforced with slaves, exiles and other malcontents.

Some Sabine bands were attempting to expand down from the region between the rivers Tiber and Anio into the Latin plain, but other incursions were simply plundering missions, and may sometimes have been stimulated by similar Roman raids into Sabine territory. The arrival of the Claudii coincided with defeat of Lars Porsenna’s army at Aricia and the loss of Rome’s hegemony over the Latins. With the additional manpower of the Claudii, Rome looked northeast to replace the territories lost in Latium Vetus. She pushed up the Via Salaria (the ‘salt road’) to the edge of Sabine territory at Eretum, picking off the Latin (or at least Latin-speaking) city-states of Crustumerium, which may have controlled a Tiber ferry crossing, and probably Ficulea (499 BC). Fidenae also fell and Roman colonists were sent to occupy its small territory and its important river crossing (498 BC). Veii was not cut off from the south by the capture of Fidenae; she could use the Tiber crossing at Lucus Feroniae in the territory of her allies the Faliscans (who spoke a language similar to Latin, but fell firmly under Etruscan influence). But Lucus Feroniae was much further upstream and therefore lacked the close convenience of Fidenae and also its strategic position on the left bank of the Tiber. Veii determined to win back the bridgehead.

Veii’s reaction was probably immediate, but the attention of the sources turns to Rome’s war against the Latin League, the Battle of Lake Regillus, the subsequent peace and the Romano-Latin-Hernican alliance against the Volsci and Aequi. Full-scale hostilities with Veii are not recorded until 483 – 474 BC (the First Veientane War). Veii had evidently won back Fidenae by this time and in an attempt to cut, or at least disrupt, her communications, Rome established a fort in the valley of the Cremera. This was manned by the gentilical war band of the Fabii, thus allowing citizen soldiers levied by the Roman state from all the other clans and voting districts to be sent to the Volscian and Aequan fronts. In 479 or 477 BC the Veientanes overwhelmed the Fabii and slaughtered them almost to a man. In the meantime, Veii had established her own fort on the Janiculum Hill. While it is unlikely that Rome was actually besieged, this garrison was a persistent irritation and in 474 BC a forty-year truce was negotiated, no doubt to the advantage of Veii.

The Second Veientane War was fought over possession of Fidenae. At some point, Rome regained control of the city, perhaps on the expiry of the truce, but the Fidenates rebelled, murdered four Roman officials sent to investigate and received military aid from Veii. In a battle outside the city, Lars Tolumnius, the king of Veii, was killed in single combat by Aulus Cornelius Cossus (the intriguing cognomen of this hero means the ‘Worm’). Cossus was only the second Roman after Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, to kill an enemy king in single combat and to dedicate the spolia opima – ‘the greatest spoils’ – to Jupiter Feretrius. The spoils included the king’s armour and perhaps also his severed head. The Romans later entered Fidenae through a siege tunnel and ransacked the city. The chronology of the war is uncertain, but 428 – 425 BC is to be preferred. Thus the Second Veientane War closely followed the great victory over the Aequi and Volsci at Algidus (431 BC). As we have seen, the war against the highlanders was to continue for decades, but a crucial corner had been turned, and Rome felt free to turn her manpower against the enemy on her doorstep.

Veii was now confined to the Etruscan bank of the Tiber but Rome still viewed her as an unacceptable rival. The dissatisfaction of the Romans with the Latin colonial system has already been noted, and they looked at the rich territory of Veii with hungry eyes and set out to annex it to the ager Romanus. It took ten years, but in 396 BC Veii was finally conquered. It is unclear how exactly the Romans captured the rocky citadel and overcame its recently-improved fortifications – the tale that it was by means of a siege tunnel is a duplication of the capture of Fidenae. Perhaps the city was simply starved into submission. It was during the course of this third and final war that the Romans instituted the stipendium, or military pay. Funded by a special tax, this payment was made in kind and in ingots of bronze (the Romans had not yet adopted coinage), allowing the army to stay in the field all year round. Military service was a requirement of citizenship, but the farmers who formed the bulk of the army could not rely on plunder to cover their debts and were always keen to be released from service as soon as possible so they could bring in their crops. When Veii fell, the Roman commander Camillus allowed the troops to sack the city and massacre its inhabitants. The booty was far richer than that taken from any of the cities or towns reconquered from the Volsci and Aequi, and the profits of the conquest were increased when the surviving Veientanes were sold as slaves. The fall of Veii and its logical incorporation into the ager Romanus marks the real start of the Roman conquest of Italy.

The addition of the ager Veientanus increased Roman territory by about fifty per cent and gave Rome a new northern frontier in Etruria. Rome could perhaps have expanded her territory into the Faliscan country as well, but, after suitable displays of force, she came to terms with Veii’s allies, Capena and Falerii (395 and 394 BC). It is indicative of the rivalry between the great Etruscan cities that, with the exception of Tarquinii, Veii did not receive any aid during the long siege.