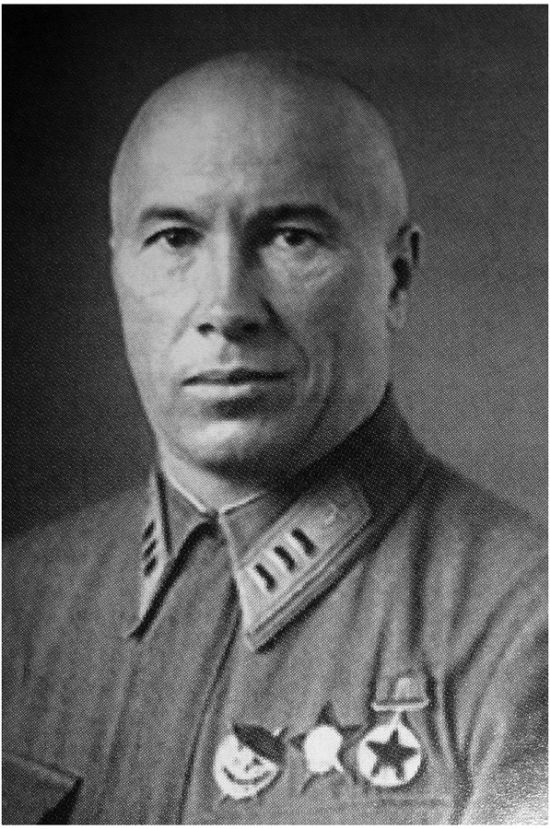

Pavel Fedorovich Zhigarev was the forgotten man of Soviet wartime air power. He was brought in immediately before the German invasion and the arrest of all three of his predecessors and held the VVS together. He was sent to Siberia in April 1942 in a dispute over aircraft deliveries, being given command of an air army in the Far East.

While the VVS objective was to provide each pilot and crew with six hours flying time and one hour of combat training per week, the severe winter weather with snow, ice and fog largely grounded the VVS. Then as the weather improved in April 1941 there were fuel shortages, so the average Baltic District pilot flew only 15.5 hours per month and the figures literally went south from there, with nine hours in the Western District and four in the Kiev District. Too often this involved little more than a quick circuit, with little attempt at formation, gunnery or bombing practice. In the Western Military Districts a return on 1 June showed there were some 10,078 pilots, of whom just over half (5,711) were officially rated as fully combat trained. Of 1,831 bomber pilots in these areas, barely a quarter were trained for night operations, while in the DBA, the figure was 223 – less than 13 per cent – out of 1,735. At the same time only 1,377 pilots were training on the new aircraft, with 399 officially rated combat worthy – 72 per cent of ‘Peshka’ pilots, 80 per cent of MiG-3 pilots and 32 per cent of LaGG-3 pilots were officially qualified on their new aircraft.

The air accident rate remained a cause for concern and, once Zhukov had settled in, Timoshenko revealed his disquiet at the VVS’s lack of preparation and Rychagov’s suitability as commander. They launched an investigation into training and presented a report to the Central Committee on 12 April 1941. This noted that poor aircrew flight discipline and maintenance meant the VVS suffered two or three fatal accidents every day, losing up to 900 aeroplanes a year. In the first quarter of the year there had been 156 crashes and 71 ‘breakdowns’ that had led to the loss of 138 aircraft and 141 aircrew. It was possibly during this meeting that, when asked to comment by Stalin on the accident rate, Rychagov retorted, ‘Of course we will continue to have many accidents as long as you keep making flying coffins.’ Stalin ominously replied, ‘You should not have said that.’

Timoshenko and Zhukov sought Rychagov’s immediate removal, and also demanded some of his officers be court-martialled. Stalin not only approved but added to the list of those who would face judgement, including DBA head Proskurov who had been in command for less than six months. He sanctimoniously commented, ‘That would be the honest and just thing to do.’ Proskurov was replaced by Polkovnik Leonid Gorbatsevich, who promptly banned Golovanov’s navigation training flights.

Yet the catalogue of accidents continued and, following the countrywide May Day parades, Shakhurin received a memo complaining about serious defects in the new aircraft issued to the Moscow and Kiev Districts. One of the first ‘Peshka’ regiments, 48th Bomber Regiment (Bombardirovochnaya Aviatsionnaya Polk, BAP), suffered numerous accidents due to airframe and engine failure, and a pilot who investigated an oil leak that caused an engine fire found a piece of rag in a fuel pipe! By the spring most of the 425 Pe-2s delivered to the VVS had suffered some form of serious defect that disrupted training to such an extent that only 100 of 1,682 aircrew were fully qualified to fly them.

This was no longer Rychagov’s problem, however, for he had been transferred to the General Staff Academy and replaced by his deputy, General-leitenant Pavel Zhigarev. The latter had transferred from the cavalry to the VVS in 1927 to become an extremely experienced officer. Zhigarev had risen steadily through the ranks (although his appointments tended to last between six and 12 months) until he transferred to Moscow in December 1940, having previously headed a Far Eastern army’s VVS. He had also led Soviet airmen in China, after which he had been head of operational training. Zhigarev was an excellent choice, and his partnership with chief-of-staff General-maior Pavel Volodin, another Far Eastern veteran, boded well.

Across the border as D-Day (Angriffstag, A-Tag) approached, the Luftwaffe and the Wehrmacht argued about how the former would open the campaign. Jeschonnek and Waldau wished to strike airfields after the Army’s artillery preparation began at dawn, but Halder feared that by then the alerted ‘birds’ would have flown. The Luftwaffe’s argument carried the day with Hitler, who decreed that the air strikes would begin at dawn, although this meant taking off from airfields that often lacked runway lights. The airmen then faced a 40-minute flight through the night and pre-dawn gloom, but the wily Luftflotten overcame the problem by using three-aircraft Ketten of experienced crews to make the initial attacks upon fighter bases, crossing the border at high altitude then swooping down on their targets.

Meanwhile, the Germans completed their preparations, the Luftflotte and Fliegerkorps commanders visiting Berlin on 4 June to receive the latest intelligence from Schmid. Eleven days later these same commanders were summoned to Göring’s home, Carinhall, for a last-minute pep talk on the same day that OKW informed its eastern armies and the Luftflotten that A-Tag would be 22 June at 0330hrs. By now the last bombs, together with boxes of food, ammunition and spares, had reached the supply depots. Heeresgruppen staff had also completed their preparations, with Bock providing Kesselring with a list of high priority targets, including the VVS signals centre at Minsk.

As they arrived in the East the bemused Luftwaffe aircrew concluded they were about to strike the Russians, but were unsure exactly when until they were roused around midnight for target briefings and the Führer’s proclamation of an Eastern Front designed to pre-empt a Russian attack. By then petrol bowsers had fuelled their aircraft, armourers had cranked bombs into bomb-bays and onto wing racks as Luftflotten and army commands transmitted coded messages at 0100hrs to indicate they were ready to attack.

The crews smoked a final cigarette, urinated over tyres or tail fins, wished each other good luck by saying ‘Break an arm and a leg’ (Hals und Beinbruchen) then climbed aboard. Soon a stream of aircraft were taking off and heading towards the glow of dawn. Russian bomber crews were also in the air because on 20 June Zhigarev had ordered an intensive night training programme that saw the last aircraft landing on the morning of the 22nd to be lined up beside the runways. Crews then made their weary way to bed while mechanics conducted checks and prepared to refuel the aircraft, whose unpainted metal finish glittered in the early morning sun.

At 0315hrs (0415hrs Moscow time) there was a glow in the west as German guns began their preparation, while in the east Luftwaffe minelayers swooped low over the approaches to the Russian naval bases of Kronstadt and Sevastopol. As the Wehrmacht crossed the frontier 15 minutes later, the Luftwaffe swooped. Soon the telephones at the Soviet Defence Ministry were ringing incessantly, each with a report of devastating air attacks. The Russians faced the continent’s largest and most battle-hardened air force at a time when their own had huge numbers of elderly aircraft lined up on overcrowded air bases. Furthermore, the VVS was hamstrung by poor communications and infrastructure, while simultaneously the NKVD had decimated the leadership cadre. It was the perfect storm!

#

In August 1941 the VVS was still adapting to its heavy losses, which meant the gradual disbandment of Frontal Aviation divisions and the growing assignment of regiments to army and front headquarters, together with RAGs. On 20 August the Defence Ministry reduced each regiment to two squadrons of nine aircraft, and two aircraft for the regimental headquarters, which would remain the basic establishment until 1943. In fighter regiments the reduction in numbers saw pilots forced to operate increasingly in pairs, although the Zveno remained official policy. In an effort to boost morale, units that had distinguished themselves were designated Guards (Gvardii), with higher pay scales and greater access to new aircraft.

By 1 October the VVS in the West had 1,540 aircraft on the main battle front supported by 472 DBA bombers and 697 PVO fighters, but increasingly numbers were made up of obsolete aircraft in the night bomber role. On that same date NBAPs, also called Light Night Bomber Regiments (LNBAP), were authorised throughout the West, with 71 formed with U-2s in October–November 1941, together with 27 regiments with R-5s and five with SBs. They were often manned by flight school students or even Osoaviakhim flying clubs, and by the end of the year the total had risen to 90 regiments.

With much of the aircraft industry in western cities, the Russians had to evacuate plants to new sites in, and behind, the Urals, where hundreds volunteered to serve in them. While the Luftwaffe was aware of this activity, it was unable to interfere. With many factories on the move, and therefore unable to renew production until the autumn at the earliest, the VVS would largely have to live off its ‘hump’. General-maior Nikolai Sokolov-Sokolenok, commandant of the aviation engineering academy, was appointed head of VVS rear services, and he began to sort order out of the chaos. This took time, however, and for months fuel and ammunition supplies were erratic – the VVS lost 70 per cent of its stocks – while the shortage of mobile workshops and spares meant repairs were slow.

To support Taifun Kesselring received reinforcements from Löhr and welcomed back Richthofen. He now had 1,320 aircraft at his disposal, which was approximately half the Luftwaffe’s strength in the East. Richthofen was not enthusiastic about supporting Bock’s left (9 Armee and 3 Panzergruppe/Panzerarmee), enveloping the West and Reserve Fronts, because the previous month’s operations had halved his strength. Loerzer’s mission was to support Bock’s right (Guderian’s 2 Panzerarmee and 4 Armee), enveloping thr Bryansk Front, using Fiebig’s 14 single-engine Gruppen for close air support while the Kampfgruppen’s 400 bombers isolated the battlefield. The offensive was preceded by a successful campaign against airfields, which left West (Michugin), Reserve (General-maior Evgenii Nikolaenko) and Bryansk (General-maior Stepan Krasovskii) Fronts with a total of only 568 aircraft on 1 October, augmented by part of 6th IAK and five DBA divisions with 158 serviceable aircraft.

The offensive began on 30 September, with Guderian, supported by 40 Flivos, striking towards Orel, which, despite opposition from every available Russian bomber, fell three days later. This allowed Loerzer to fly in supplies for Fiebig, including 500 tonnes of fuel. Already the second stage of the offensive was underway, as Bock’s left punch was thrown on 2 October, with 1,387 sorties, followed by 971 the next day. These helped the Panzer spearheads to meet at Vyazma on 7 October, supported by some 800 bomber sorties. A Russian heavy bomber squadron at Vyazma was saved when ad hoc pilots, including a flight engineer and a paratrooper, flew out all the aircraft. The remaining Soviet personnel were mopped up by 20 October, with Luftwaffe help.

In the aftermath of this defeat uncertainty created panic in Moscow, and from 15 October thousands fled. When Golovanov drove from the city centre to a nearby airfield he was angry to be informed by a newly arrived Er-2 pilot of Moscow’s capitulation. Towards the end of October the NKVD executed dozens of generals in its custody, including most of the VVS and PVO leaders. A desperate Stalin frequently rang Zhigarev’s headquarters, only to receive soothing, but inaccurate, responses from the VVS commander. Air operations were further hindered by his frequently conflicting orders. Zhigarev coordinated a 937-sortie campaign against airfields between 11 and 18 October to relieve the pressure upon the encircled troops, but without noticeable effect, and used TB-3 transports to send supplies to the front.

As the situation deteriorated it was Sbytov, now the Moscow District VVS commander, whose fighter regiments ended the uncertainty with tactical reconnaissance missions. One patrol discovered the enemy breakthrough on 5 October, and 95 aircraft, including a squadron made up of instructors, struck the spearhead. So great was the threat, however, that Russian groundcrews carried grenades to defend their airfields.

By 10 October, 6th IAK, which was defending Moscow from both air and ground attack, was down to 344 serviceable fighters. Some were flying five to six sorties per day – a pace maintained due to the surplus of pilots. The corps would be the first to benefit from foreign aid when, on 12 October, its 126th IAP became operational on American-made Tomahawk fighters delivered by the British, although their vulnerability to Russian winters made them a slender reed. Five days later a Kalinin Front was created on West Front’s right, with General-maior Nikolai Trifonov hastily cobbling together the air support. By 1 November he had only 89 aircraft, including 56 fighters.

The Russians claim the VVS flew 26,000 sorties to the end of October, 80 per cent in direct support of the troops, but suffered heavy losses due to other problems. Contact with Moscow was frequently lost, partly due to the shortage of radios, which hindered air strike coordination and establishing FEBA location. On 6 October Zhigarev demanded his subordinates establish command posts alongside those of the armies, with clear maps of the situation, but often VVS officers could discover the FEBA only by flying over the front in a U-2.

#

Throughout the winter 1941-42 Moscow suffered intermittent bombing. As early as 8 July 1941, Halder had noted Hitler wished to destroy Moscow and Leningrad through air attack, and five days later Richthofen stirred the pot by claiming Moscow’s destruction would help the Wehrmacht’s advance. But permission was not given until Weisung Nr 33 on 19 July, when Loerzer received three Kampfgruppen from the West (61 bombers) to bring Kesselring’s force to 11 Kampfgruppen. The following day he briefed his commanders on the new operations, which would be supported by X-Geräte beacons to support KGr 100’s pathfinders.

The defence of Moscow was the PVO’s prime mission, and for this task 6th IAK PVO was created two days before the invasion with 389 fighters, including 175 new LaGG-3s, MiG-3s and Yak-1s and 68 nightfighters. It also had some experienced pilots, a few of whom had 400 hours in their log books. ObdL sent a reconnaissance aircraft so high over Moscow on the first day of the war that it was not detected, and from 8 July the reconnaissance effort intensified. There was tension between IAK commander Polkovnik Ivan Klimov, who wished to direct the fighters from his command post, and his superior, the PVO area commander General-maior (General-leitenant from 28 October 1941) Daniil Zhuravlev, who wanted him to operate from the regional headquarters. Yet Zhuravlev’s command still relied largely on wire communications, which slowed reaction times, with cloth panels used to direct fighters in daylight, as in World War I.

The first raid by 195 bombers on the night of 22/23 July used burning Smolensk as a beacon, and dropped some 200 tonnes of bombs. It briefly forced Stavka into a Metro station, from whence it re-emerged as the bombing eased. Raids were detected by a RUS-2 radar manned by experts, and this led to about 175 sorties by single-engined fighters. Nevertheless, the Germans lost only six bombers. The following two nights saw raids by some 225 bombers, but there was a lull during August, apart from 83 bombers striking on 10/11 August, while Kesselring built a chain of 16 radio navigation beacons and Zhigarev stripped eight IAPs from Klimov to reinforce 6th IAK. In an attempt to restrict the Germans the Russians despatched Pe-2s and Yak-4s to trail the bombers to their bases, which were then subjected to attack. The Luftwaffe would repeat this concept, with spectacular success, against the Russians and their American allies in the summer of 1944.

Anti-aircraft artillery was the backbone of the PVO throughout the war, with fighters assigned a complementary role. Partly for this reason, and partly because it was newly established, 6th IAK lacked equipment when Germany invaded – it had only 39 engine starters out of an establishment of 110 and 40 petrol bowsers instead of 165. Only 147 pilots were combat trained, 88 on new fighters, and eight of them were qualified to fly nightfighters. In mid-July test pilots were hastily assembled to form two nightfighter squadrons, equipped with SBs and Pe-2s. Klimov tried to bring order out of chaos, but his bullying attitude, with frequent threats of court martial, was resented. In fact the decision to split the Moscow air defence area into four sectors for fighters reportedly came from Stalin himself. With the eyes of Stalin upon him, Zhigarev built up the Moscow PVO, which had 719 fighters on 17 July and was promptly reinforced by four regiments of veteran pilots from the front.

The Luftwaffe’s effort against Moscow gradually tailed off, and while there were 23 raids involving 289 sorties during October, these were minor irritations rather than serious attacks. The Luftwaffe’s lack of bombers, rather than Soviet resistance, was the key to Moscow’s success, with the last night raid on 5/6 April 1942, concluding a campaign of 11 day and 76 night attacks – six by 50 aircraft and 59 by less than a dozen bombers. There were another 94 sorties flown over Gorki from 4 to 6 November.

The PVO generated 1,015 nightfighter sorties in July and 840 in August (out of 8,065 and 6,895 nationally, respectively), with most Soviet nightfighters being single-engined aircraft which, like the RAF in 1940, depended upon the bravery and skill of their pilots for success. They were crudely converted with flame-dampers, but none had radar, while the few illuminated runways often remained dark because groundcrews feared attracting the enemy. Development of a ‘Peshka’ fighter, the Pe-3, began during August 1941, although production would be diverted to both bomber and reconnaissance regiments and a radar-equipped version would not be evaluated until April 1942. By then Klimov had gone, possibly a victim of his conflict with Zhuravlev and general dislike within the PVO, and he was replaced on 8 November by Polkovnik Aleksei Mitenkov.

From January 1942 observer posts began to receive radios for GCI, and each fighter sector had a RUS-2 radar to help provide information on the tactical situation. During the first year of the war these radars guided 149 interceptions in which 73 victories were claimed, aided by the introduction of RUS-2S, which had a height-finder capability.

#

As the spring rasputitsa ended the winter fighting, Stalin took stock, and the VVS did not escape his attention. It had achieved much, but there was no escaping the fact that usually the Luftwaffe dominated the skies and the buck stopped at Zhigarev’s desk. This may explain why Zhigarev left so slight a footprint in the sands of time, for he is mentioned in few memoirs and usually in lists of ‘spear carriers’ who contributed to the success of offensives.15 In part this was because, like most Russian managers, he cringed before his superiors and cowed his subordinates. On one occasion Novikov was visiting an airfield when a TB-7 – an aircraft he had never seen before – landed, and as he inspected it he encountered VVS Commissar Pavel Stepanov, who introduced him to Zhigarev. Novikov asked if there was anything he could do to help, and was brusquely told, ‘Mind your own business. We can do without you.’ Zhigarev then drove off.

Whatever his lack of social skills, Zhigarev was a hard worker and skilled administrator. Rudenko, one of his few friends, said he had a penchant for research. He undoubtedly played a major role in keeping the VVS together in trying times along with his chief-of-staff from August 1941, General-maior (General-leitenant from 29 October) Grigorii Vorozheikin, a former, and future, ‘guest’ of the NKVD. It is likely that reforms driven by his successor Novikov were based upon Zhigarev’s foundations, but the former Leningrad air commander had powerful friends in Zhukov and Andrei Zhandov, as well as being a more dynamic personality.

The cause of Zhigarev’s dismissal on 11 April 1942, was a dispute between him and Aviation Minister Shakhurin over the former’s failure to provide pilots to pick up new aircraft from factories. Zhigarev claimed the aircraft had not been formally accepted, but when General-leitenant Nikolai Seleznev (the VVS Supply Director) was called in he confirmed the aircraft simply lacked pilots to ferry them. A furious Stalin called Zhigarev a scoundrel and told him to go. Yet Stalin appreciated his skills, and he was neither demoted nor disgraced, instead being given command of the Far Eastern VVS, where he was briefly an air army commander during the 1945 war with Japan.

Zhigarev’s post-war career waxed as Novikov’s waned, for in succession he commanded the ADD and then the VVS, before becoming Defence Minister. In 1959, as head of civil aviation, he signed an agreement establishing civil air links between London and Moscow. On the day he was relieved as VVS commander he left it a legacy by authorising evaluation of the LaGG-3 fitted with the M-82 radial engine. The resulting combination soon became the outstanding La-5 fighter.