The Deir el-Bahri mortuary temple, Djeser-Djeseru, provides us with evidence for defensive military activity during Hatchepsut’s reign. By the late nineteenth century Naville had uncovered enough references to battles to convince him that Hatchepsut had embarked on the now customary series of campaigns against her vassals to the south and east. These subjects, the traditional enemies of Egypt, almost invariably viewed any change of pharaoh as an opportunity to rebel against their overlords, while the pharaohs themselves seem to have almost welcomed these minor insurrections as a means of proving their military might:

The fragments and inscriptions found in the course of the excavations at Deir el-Bahri show that during Hatchepsut’s reign wars were waged against the Ethiopians, and probably also against the Asiatics. Among these wars which the queen considered the most glorious, and which she desired to be recorded on the walls of the temple erected as a monument to her high deeds, was the campaign against the nations of the Upper Nile.

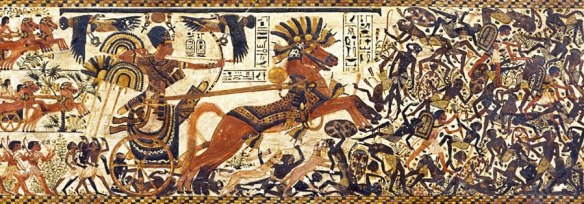

Blocks originally sited on the eastern colonnade show the Nubian god Dedwen leading a series of captive southern towns towards the victorious Hatchepsut, each town being represented by a name written in a crenellated cartouche and topped by an obviously African head. The towns all belong to the land of Cush (Nubia). Elsewhere in the temple, Hatchepsut is portrayed as a sphinx, a human-headed crouching lion crushing the traditional enemies of Egypt. There is also a written, but unfortunately badly damaged, description of a Nubian campaign in which Hatchepsut appears to be claiming to have emulated the deeds of her revered father:

… as was done by her victorious father, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Aakheperkare [Tuthmosis I] who seized all lands… a slaughter was made among them, the number [of dead] being unknown; their hands were cut off… she overthrew [gap in text] the gods [gap in text]…

The evidence from the Deir el-Bahri temple is a mixture of official pronouncements and conventional scenes, and it is therefore possible that the Nubian campaigns may be battles which Hatchepsut has ‘borrowed’ from earlier pharaohs, possibly her father. Such borrowing or usurping, disgraceful cheating to modern eyes, would have been entirely in keeping with Egyptian tradition which stated that the pharaoh had to be seen to defeat the enemies of Egypt; those who did not actually fight simply invented or borrowed victories which, as they depicted them, became real through the power of art and the written word. This means that a formal inscription carved by a king of Egypt and unsupported by independent collaborative evidence can never be taken as the historical truth. However, an unofficial graffito recovered from the Upper Egyptian island of Sehel (Aswan), and written on behalf of a man named Ti who served under both Hatchepsut and Tuthmosis III, confirms that there was indeed some fighting in the south during Hatchepsut’s reign:

The Hereditary Prince and Governor, Treasurer of the King of Lower Egypt, the Sole Friend, Chief Treasurer, the one concerned with the booty, Ti. He says: ‘I followed the good god, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Maatkare, may she live! I saw him [i.e. Hatchepsut] overthrowing the Nubian nomads, their chiefs being brought to him as prisoners. I saw him destroying the land of Nubia while I was in the following of His Majesty…’

Ti goes further than the Deir el-Bahri evidence in suggesting that Hatchepsut was actually present during the fighting in Nubia. He himself was present at the battle not as a soldier, but as a bureaucrat. Further confirmatory evidence for at least one Nubian campaign comes from the tomb of Senenmut, where a badly damaged and disjointed series of inscriptions read ‘I seized…’ and later ‘the land of Nubia’, and from the stela of a man named Djehuty, a witness to the southern fighting, who tells us that he actually saw Hatchepsut on the field of battle, collecting the spoils of war.

There is less direct evidence for military campaigning to the north-east of Egypt, although again the Deir el-Bahri temple does hint at some skirmishes; in at least one inscription it is said of Hatchepsut that ‘her arrow is amongst the northerners’. However, it is a consideration of the subsequent conquests of Tuthmosis III which provides the best evidence for the maintenance of firm military control over the northeastern territories. When Tuthmosis III eventually became sole ruler of Egypt, the client states in Syria and Palestine seized the traditional opportunity to rebel, a reaction which suggests that the death of Hatchepsut may have been viewed as a potential weakening rather than strengthening of Egypt’s power in the Levant. The Egyptian army, however, had been properly maintained, the soldiers were ready, the correct administration was in place, and Tuthmosis was able to launch an immediate and successful counter-attack. Tuthmosis, in his role as head of the army throughout the latter part of the co-regency, had already conducted at least one successful campaign in Palestine, during which he had captured the strategically important town of Gaza; by Year 23, the first year of Tuthmosis solo reign, Gaza is described as ‘the town which the ruler had taken’. Tuthmosis went on to become one of Egypt’s most successful generals, pushing back the eastern and southern boundaries of the Egyptian Empire until Egypt became without doubt the dominant force in the Mediterranean world. Would his career have been so brilliant had it not been preceded by the reign of Hatchepsut?

Hatchepsut’s military policy is perhaps best described as one of unobtrusive control; active defence rather than deliberate offence. While either unwilling or unable to actually expand Egypt’s sphere of influence in the near east, she was certainly prepared to fight to maintain the borders of her country. Her military record is in fact stronger than that of Tuthmosis II, who did not lead his campaigns in person, and far more impressive than that of Akhenaten, a male king who showed an extreme reluctance to protect his own interests even though he received a stream of increasingly desperate letters from his Levantine vassals begging him for military assistance. It would certainly be very unfair to draw a direct comparison between the campaigns of Tuthmosis I, Tuthmosis III and Hatchepsut, and then criticize the latter for not adopting a more aggressive stance. It is, in fact, Tuthmosis III who is unusual in this line-up; all the other 18th Dynasty pharaohs embarked on the customary campaigns towards the beginning of their reigns, but only Tuthmosis III made fighting his life’s work. After all, although a good military record was a desirable aspect of kingship, not all kings could be lucky enough to participate in a decisive military campaign. The fact that Hatchepsut did not need to fight may actually be taken as an indication of strength rather than weakness. The most successful 18th Dynasty monarch, Amenhotep III, a king who ruled over Egypt at a time of unprecedented prosperity, certainly had a less than impressive war record. This was not through personal cowardice or adherence to a deliberate policy of peace; Amenhotep III did not fight because he did not need to. Throughout his rule Egypt remained the greatest power in the Mediterranean world and, rather than rebel, Egypt’s vassals and neighbours stood in awe.