During the fierce air fighting that characterised the last two years of the First World War, the Sopwith Camel destroyed more enemy aircraft than any other Allied fighter. To those pilots who mastered its vicious idiosyncracies, and turned them to their own advantage, it was a magnificent fighting machine; to those who did not, it was a potential killer.

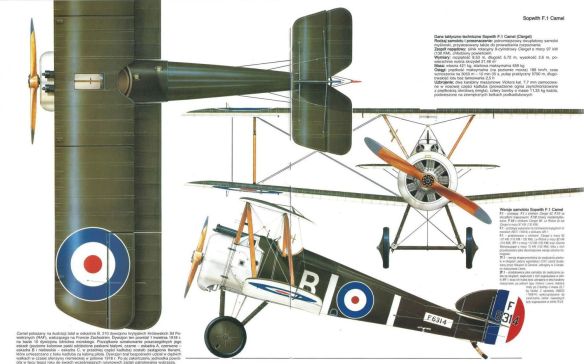

The little biplane that became known as the Camel was designed by the Sopwith company as a successor to their graceful Pup and elegant Triplane. Armed with two fixed Vickers machine-guns and powered by a Clerget rotary engine, the new fighter was designated Sopwith F.1, the prototype emerging a few days before Christmas 1916. It was not a pretty aircraft; the adjectives stocky, pugnacious, stumpy and purposeful all fitted it perfectly.

The first thing that struck people was its compact nature. The Clerget engine was on an overhung mounting and was fitted with a circular cowling. The oil tank was situated immediately behind the engine back-plate and the guns were mounted above, their twin muzzles level with the front of the engine cowling. The cockpit was situated as far forward as possible, the pilot’s feet virtually under the carburettor, his face close to the butts of the machine-guns. He sat in a wicker seat, immediately behind which was the main fuel tank. Each mainplane had two main spars, and the profiles of all flight surfaces were formed of steel tubing. The lower wing had a pronounced dihedral angle of five degrees, which contrasted sharply with the lack of dihedral on the upper wing. Ailerons were fitted to both upper and lower wing surfaces. With the emergence of the first prototype, one flaw became immediately apparent; the aircraft had been built with no central cut-out in the centre section of the upper wing, which meant that the pilot was blind in a steep turn. A central cut-out was built into the second and subsequent machines.

The breech mechanisms of the twin Vickers guns were covered by a high forward decking. On the first prototype, this sloped upwards to the forward edge of the cockpit, forming a kind of windscreen. This gave the forward fuselage of the F.1 a humped appearance which, so the story goes, is how the aircraft came to be called the Camel. This name was never adopted officially, the aircraft continuing to bear the official designation Sopwith Biplane F.1. Subsequent aircraft had a horizontal decking, and were fitted with a small transparent windscreen.

Early production aircraft were powered either by the 130 hp Clerget 9B or the 150 hp Bentley BR1 rotary engine, but later aircraft were fitted with either the Clerget or the 110 hp Le Rhone 9J. The rotary engine was attractive for fighters because it had a very good power/weight ratio – much better than an equivalent stationary engine – and it was very compact. Probably the best of them all was the Bentley BR2, which came along at the end of 1917. The excellent power/weight ratio was a by-product of the circumferential layout of the cylinders, which saved a lot of crankcase weight, and from the fact that the cooling was provided by the cylinders whirling round in the air stream. This permitted a very light steel cylinder, with minimum cooling fins.

In the air, however, having the main engine mass whirling round at about 1250 rpm introduced some peculiarities not apparent in stationary-engined aircraft. Of these, the most obvious was gyroscopic action. There was also a considerable increase in torque reaction, which tried to rotate the airframe in the opposite direction to the rotation of the engine. As one former Sopwith Camel pilot put it:

Some people, particularly learner pilots on Camels, regarded this mysterious gyroscopic action – it was very fierce on Camels – as a species of black magic malevolently exercised by a venomous aircraft to imperil the safety of its pilot; but if one took the trouble to understand it, this bogey of personal malevolence faded out and was replaced by a comforting knowledge of what was going on and what had to be done about it.

A gyroscope is any sort of spinning mass – like an ordinary spinning top – and the whirling mass of some 350 lb of engine at 1250 rpm constitutes a gyroscope of quite sizeable proportions. The outstanding feature of a gyroscope is that it likes to stay in the geometric plane in which it is spinning. If the axis of rotation is turned, as in turning the aeroplane, the gyroscope, following its urge to stay put, registers a strong protest by tilting on an axis at right-angles to the desired axis of turn. In terms of practical flying this means that if, with an engine rotating clockwise as seen from the pilot’s seat, you turn to the right, the gyroscopic effect will give a sharp nose-down reaction; or, if you turn to the left, it will give a nose-up effect. Similarly, a sudden climb produces a strong swing to the right and a dive produces a swing to the left. These effects are, of course, present in a small degree on any propeller-driven aircraft, but in some of the rotaries they were really fierce.

In the Camel, the engine, guns, pilot and fuel were all concentrated at the front end of the fuselage, which made response to rudder and elevators very lively. It also made response to the queer effects of gyroscopic action very lively, too. So much was this so, with the heavier engine, that gyroscopic effect became quite a problem and on sudden changes of direction the Camel could, and with unwary pilots often did, run out of rudder control – sometimes with disastrous results. To this rather daunting characteristic was added an unusual readiness to spin, presumably a side effect of the compact concentration of weight.

In his book Recollections of an Airman, Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Strange, an experienced Camel pilot who served with the Central Flying School at Upavon, Wiltshire, from April 1917 to March 1918, wrote:

In spite of all the care we took, Camels continually spun down out of control when flown by pupils on their first solos. At length, with the assistance of Lieut Morgan, who managed our workshops, I took the main tank out of several Camels and replaced it with a smaller one, which enabled us to fit in dual control. When the first of these adapted machines was ready, Morgan was my passenger on its first flight.

Two-seat Camel conversions were also made at other flying establishments, and dual instruction went some way to alleviating the unacceptable casualty problem during the critical training phase.

The first unit to receive Camels was No. 4 Squadron RNAS, followed by No. 70 Squadron RFC, both in July 1917. By the end of the year 1325 Camels (out of a total of 3450 on order at that time) had been delivered, and were used widely for ground attack during the Battles of Ypres and Cambrai. In March 1917, meanwhile, a shipboard version of the Camel, the 2F.1, had undergone trials; designed to operate from platforms on warships, from towed lighters or from the Royal Navy’s new aircraft carriers, this differed from the F.1 in having a slightly shorter wing span. Also, instead of the starboard Vickers gun, it had a Lewis gun angled to fire upwards through a cutout in the upper wing centre section. The 2F.1’s principal mission was Zeppelin interception; 340 examples were built, but the first of these did not become operational until the spring of 1918. By the end of the war, however, 2F.1 Camels were deployed on five aircraft carriers, two battleships and twenty-six cruisers of the Royal Navy. On 11 August 1918, a 2F.1 Camel flown by Lieutenant Stuart Culley, and launched from a lighter towed behind the destroyer HMS Redoubt, intercepted and destroyed the Zeppelin L.53 over the Heligoland Bight.

Early in 1918, with an increase in night attacks on southern England by German heavier-than-air bombers, several home-based night-fighter units rearmed with the Sopwith Camel. The cessation of night attacks in May meant that aircraft could be released for service in the night-fighting role on the Western Front. In June, No. 151 Squadron, a specialist Camel-equipped night-fighting unit, moved to France and began operations against Gotha night bombers and their airfields.

At the end of October 1918 the RAF had 2548 Camel F.1s on charge, and 129 2F.1s. By this time the Camel was already being replaced by the Sopwith Snipe, but it continued to serve for some years after the war with the Belgian Aviation Militaire, the Canadian Air Force, the Royal Hellenic Naval Air Service, the Polish Air Force and the US Navy.

The last RAF squadron to use the Camel in combat was No. 47, which deployed to southern Russia in March 1919 to support the Allied Intervention Force, in action against the Bolsheviks. During the same period, Camels operating from the carrier HMS Vindictive flew in support of Allied forces resisting Russian advances into the Baltic States.

The Camel’s fighting prowess is well illustrated by a few accounts of its actions on the Western Front in 1918, when it really came into its own. The following is an extract from the war diary of No. 43 Squadron, then based at La Gorgue under the command of Major C.C. Miles.

17 February. Trollope’s patrol of five Camels encountered an enemy formation of eight machines. As a result of the combat which ensued three enemy machines were driven down out of control.

18 February. Captain Trollope while on a special mission (alone) saw three Armstrong Whitworths under attack by six enemy machines. He at once attacked the enemy who were then joined by six more. Trollope fought the twelve for ten minutes until all his ammunition was exhausted, by which time the enemy machines had all flown away to the east.

19 February. Second Lieutenant R.J. Owen whilst on patrol on his own was attacked by five enemy scouts in the vicinity of the Bois de Biez. He fought the five, one of which according to the testimony of antiaircraft gunners was seen to fall in flames.

26 February. Captain Trollope leading a patrol of nine Camels saw four DFWs escorted by fifteen enemy scouts. He led the patrol into the attack. Although gun trouble prevented him from joining in he stayed in the middle of the fight and saw two enemy machines crash and a third fall out of control.

At the beginning of March 1918, there were plenty of indications that an expected German offensive in Flanders was not far away. Despite continuing bad weather the enemy’s air effort intensified, with much activity by observation aircraft. There were some brisk engagements, and on 13 March seven Camels of No. 43 Squadron, escorting a pair of FK.8s, encountered a mixed force of fifteen Albatros and Pfalz scouts and attacked them; Captain Henry Woollett fired at one, which broke up in mid-air, then engaged a second, which went out of control and crashed. Two more were shot down by 2nd Lieutenant Peiler, and one each by 2nd Lieutenants Lingham, Lomax, King and Dean. A ninth enemy aircraft was shot down by an observer in one of the FK.8s, which belonged to No. 2 Squadron, whereupon the remainder broke off the action and flew away.

On 16 March, seven Camels of No. 4 (Australian) Squadron, which was part of the 10th (Army) Wing, took off from Bruay to attack targets near Douai with 20 lb bombs. The attack was carried out without incident, but as the Camels were climbing to 16,000 feet to cross the front line they were hotly engaged by a formation of sixteen brightly painted Albatros scouts, readily identifiable as belonging to the Richthofen Geschwader. While four of the Albatros remained at altitude, ready to dive down and pick off stragglers, the other twelve attacked in pairs. The Australian flight commander, Lieutenant G.F. Malley and Lieutenant C.M. Feez avoided the first pass and went in pursuit of the two Albatros, which were diving in formation. The Australians shot both of them down. Meanwhile, Lieutenant A.W. Adams, some 2000 feet lower down, fought a hectic battle with two more Scouts and destroyed one of them, while Lieutenant W.H. Nicholls, pursued down to ground level, was forced to land behind the German lines and was taken prisoner. Another Camel pilot, Lieutenant P.K. Schafer, was attacked by three Albatros of the high flight; as he was attempting to evade, the Camel flicked into a spin and fell 10,000 feet before the shaken Australian managed to recover. He landed at Bruay with sixty-two bullet holes in his aircraft. On the following day, Captain John Trollope of No. 43 Squadron sighted six enemy Scouts while flying alone on an altitude test (a favourite ploy of pilots lacking the necessary authorisation to carry out lone patrols over the front line). He climbed above them and attacked, sending one down out of control. The other five dived away. Shortly afterwards, while returning to base, Trollope sighted four more enemy aircraft and attacked one of them at close range. It caught fire and broke up. Trollope at once turned to engage the rest, but they flew away eastwards.

The big German offensive was launched on 21 March 1918. Some fighter squadrons, which had been operating from bases outside the immediate battle area, were now moved closer to it in order to provide escort for the all-important ground attack and observation aircraft, and to establish the air superiority that was so vital to the RFC’s effort. One of them was No. 43 Squadron, which moved from La Gorgue, near Merville, to Avesnes-le-Comte near Arras. On the first patrol on 24 March, Captain John Trollope, leading a flight of Camels, sighted three DFW two-seaters and worked his way round to the east to cut off their line of escape. He closed in and fired at the first, but then his guns jammed. After clearing the stoppage he engaged the second DFW and fired 100 rounds at it, seeing it break up in mid-air; he at once closed on a third and set it on fire. Meanwhile, the first DFW had been engaged by Captain Cecil King and 2nd Lieutenant A.P. Owen, who continued to fire at it until it too broke up. Some Albatros scouts arrived belatedly to protect the D.F.W.s, and Trollope immediately shot one down. At a lower level, another flight of No. 43 Squadron Camels led by Captain Henry Woollett was engaging more D.F.Ws, one of which Woollett set on fire. Lieutenant Daniel of Woollet’s flight, losing contact during the engagement, joined up with No. 3 (Naval) Squadron, which attacked five Pfalz scouts. Daniel destroyed one of them, bringing No. 43 Squadron’s score on that patrol to six.

That afternoon, Trollope led a second patrol into action, despite deteriorating weather conditions. Soon after crossing the front line he sighted four enemy two-seaters attacking a pair of RE.8s; five or six German single-seat fighters were also in the vicinity. Trollope led his pilots down to the aid of the REs and he singled out one of the two-seaters, firing in short bursts as he closed in to almost point-blank range. He saw pieces fly off the enemy aircraft’s wing, and then the whole wing collapsed. Turning hard, Trollope came round for a stern attack on another two-seater, running through heavy defensive fire from the German observer as he did so. A few moments later the German was dead in his cockpit and the aircraft spiralling down in flames. Almost at once, Trollope engaged a third two-seater which was flying at very low level; after a short burst of fire the enemy aircraft nose-dived into the ground, disintegrating on impact.

Pulling up, Trollope saw one of the squadron’s Camels hard-pressed by a dozen German scouts, so he climbed hard to assist, soon joined by 2nd Lieutenants Owen and Highton. He saw each of these pilots destroy an enemy aircraft and engaged one himself, but then his ammunition ran out and he was forced to break off. In the afternoon, nine Camels led by Captain Henry Woollett fired 6800 rounds in strafing attacks on enemy troops, and Woollett also shot down two observation balloons. By the end of the day, Lieutenant ‘Bert’ Hull, No. 43 Squadron’s records officer, could report to his CO, Major Miles, that the unit had broken all previous records, having destroyed twenty-two enemy aircraft without loss in the day’s fighting. The destruction of six by Captain Trollope in a single day had created a new RFC/RNAS record. There could have been no finer vindication for the aircraft they called a killer.