No other general was more current with the situation on the ground than Richthofen. When duty did not absolutely require him to be inside his command post, he was either up near the front with his specially equipped signals units — or he was over enemy territory in the cockpit of a Fiesler Storch doing personal reconnaissance. He had already been shot down once, on the first day of the war, by flak that crippled his light plane but left him unharmed. Richthofen had at his beck and call a reconnaissance squadron, two Stuka groups, a group of Me.110s, and a group of ground-attack planes that looked like updated versions of World War I fighters. Thus, like a surgeon or a master carpenter, Richthofen could reach for the right tool to do the job at hand.

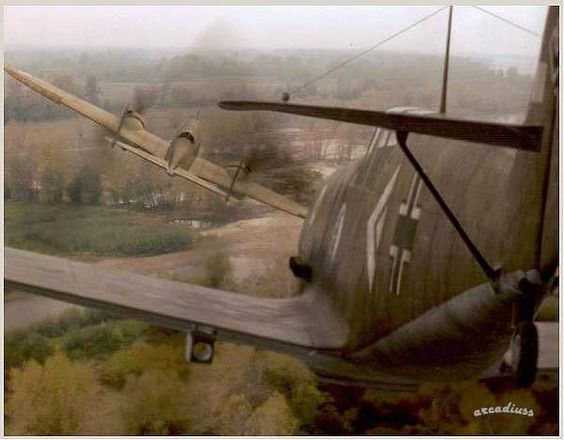

The biplanes assigned to the air operations around Kutno were HS.123A-IS, built around a massive BMW 880-horsepower radial engine that provided a top speed of just over 210 miles per hour. But neither speed nor ceiling mattered with the Hs.123, which was meant to operate right down on the deck; five hundred feet was considered extreme altitude to the pilots who flew these ground-attack planes. The “Ein-Zwei-Drei,” as it was sometimes called, could carry a variety of armament: a pair of twin 7.9-millimeter machine guns firing through the propeller, or a pair of 20-millimeter cannon in pods under the wings, or underwing containers loaded with ninety-four small (4.4 pound) antipersonnel bombs, or four 110-pound high explosive bombs. Moreover, the HS.123s carried a small auxiliary fuel tank underneath the fuselage fitted with a special igniter so that it could be jettisoned with a napalmlike effect, a tactic borrowed from He.51 units operating with the Condor Legion in Spain. Originally designed as a dive-bomber and built by Henschel, the locomotive-makers, the solid Hs.123 could absorb more flak than any other Luftwaffe plane in service and still keep flying. Protected by the big radial engine in front, and with an armored headrest at the rear, Hs.123 pilots’ chances of survival when operating at zero altitude were better than most. The Henschels had proved themselves in Spain from 1937 onward, but in Poland they were a sensation.

The Hs.123 group, II/L.G.2, began the war with thirty-six operational planes, and after ten days of almost continuous action, thirty still remained. Richthofen threw them all against Kutrzeba’s assault forces late in the morning of September 11. The Henschels roared down on the Polish concentrations in a corridor thirty to fifty feet high separating the Poles from the Germans.

To Kutrzeba’s men, almost none of whom had been under air attack before, the next twenty minutes were like a nightmare in hell. The machine guns cut swaths in the ranks of men and horses; hundreds of the lightweight scatter bombs flamed and exploded; the heavier detonations of the 110-pounders tore gouts out of the earth, ripped through trees and flung jagged metal shards thudding into men and animals. Even when the last of the various missiles had been delivered, the 123s were not finished with their low-level attacks: the pilots discovered that when the BMW engine was pushed to 1,800 rpm, the resultant effect on the three-bladed, variable-pitch airscrew produced an ear-splitting and indescribable sound that was both inside and outside of the man subjected to it. Even hardened soldiers were unnerved, and ran in all directions to escape; horses simply went insane. The Henschels were followed by Stukas, which were followed by Dorniers and Heinkels pulled out of the battle for Warsaw, and they in turn were followed by cannon and machine-gun-firing Me.110s. The assault on the battered 30th Infantry Division was stopped cold, and the survivors of the day-long air attack began withdrawing across the river under the merciful cover of darkness. The wounded were, for the most part, brought back aboard whatever vehicles were left, and cavalrymen walked through the carnage left by Richthofen’s pilots’ putting pistol and rifle bullets into the heads of the wounded horses.

Dawn brought the return of the Henschels and a repetition of the horrors of the day before. The Army of Poznan was forced back into its twenty-by-thirty-mile enclave that became a Luftwaffe shooting gallery. The Poles replied with rifles, machine guns, and light flak, knocking down some of their tormentors, but the numbers thrown at the pocket from all around the compass were overwhelming. No square foot of that blasted area was safe. Recalled General Kutrzeba: “A furious air assault was made on the river crossings near Witkovice which, for the number of aircraft engaged, the violence of their attack and the acrobatic daring of their pilots, must have been unprecedented. Every movement, every troop concentration, every line of advance came under pulverizing bombardment from the air … The bridges were destroyed, the fords blocked, the waiting columns of men decimated … Three of us found some sort of cover in a grove of birch trees outside the village of Myszory. There we remained, unable to stir, until about noon when the air raids stopped. We knew it was only for a moment, but had we stayed there the chances of any of us surviving would have been slight.”

Kutrzeba tried to fight his shaken forces out of the trap and the hell of air attack, but found himself fenced in on all sides by the German Fourth, Eighth, and Tenth Armies, part of the latter having been ordered back from the siege of Warsaw to complete the encirclement of the Army of Poznan. On the sixteenth and seventeenth, the Luftwaffe delivered all-day attacks on the shrinking perimeter, and after that resistance was futile. Fifty thousand haggard Polish soldiers surrendered on the next day, and 105,000 gave themselves up on the day afterward. A few thousand of Kutrzeba’s men managed to escape through the German net before it was drawn too tightly, wading through marshes by night and hiding by day. But all the rest were either herded into captivity or lay mute in the fields and in the forests around Kutno.

At first light on the morning of September 17, Russian tanks and infantry rolled into Poland. The advance was swift and orderly against practically no opposition; what was left of the Polish army was penned inside Warsaw, surrounded by German armor at Modlin and in the Kampinoska Forest thirty miles north of the capital, while a pitifully small number of troops were still fighting desperately with their backs against the sea trying to hold Gdynia and Danzig, which the Poles called Gdansk. As agreed in Moscow three weeks earlier, the Red Army ground through Poland until it reached the partition line halfway across the country, a line running south from East Prussia past Brest-Litovsk and to the Carpathians. There the Soviets halted, waiting for the Wehrmacht to finish the kill; the carcass had already been divided.

The Wehrmacht used all its arms to methodically reduce the pocket of resistance on the Baltic. The area here is flat and featureless, except for a low ridge stretching seven miles inland from the sea. Initial advances across the hard sand were stopped by vicious and accurate Polish machine-gunning and heavy rifle fire. With no wish to incur needless casualties, the assault elements of the Third Army moved in its heavy artillery and began bombarding the area with high explosive. The fire was regulated by one of the German navy’s Heinkel reconnaissance planes that buzzed overhead, wirelessing back corrections. The small island of Westerplatte, lying in the sea just off Danzig, stubbornly resisted the shelling and the tentative infantry advances. During the shelling, Polish defenders took shelter in one of the huge steel-and-concrete bunkers that proved impervious to the guns the German artillery had at hand. The battleship Schleswig-Holstein anchored in the bay and opened up with its eleven-inch guns. The concrete was seared and pitted, but still the great dome of the bunker remained intact. Then Stukas were called in, and in the ensuing half hour succeeded where the battleship had failed. The 550-pound bombs delivered with stunning accuracy smashed through ten feet of reinforced concrete to mangle everyone inside. Those who had sought cover in trenches because there was no more room inside the bunkers counted themselves lucky. The Westerplatte fell, and in a gesture reminiscent of the nineteenth century, the German commander allowed his Polish counterpart to retain his sword as a Wehrmacht tribute to Polish courage. There now remained Warsaw, whose ordeal had lasted longer than that of any other city in Poland.

Trapped inside the beautiful old city were nearly a hundred thousand Polish troops. They were joined in trench-digging and in converting buildings to strongpoints by civilian men, women, and even children determined to defend the city to the last. On the day after the Russians crossed the Polish frontier, the leaders of the government and even Field Marshal Smigly-Rydz made their way out of the doomed country and sought temporary sanctuary in Rumania. Leaderless, Warsaw fought on.

The skies over the city were never free of German planes. All that was left to defend Warsaw was a spontaneously formed unit calling itself the Deblin Group, composed of older P.7s, what was left of the P.11s, and one example of a PZL P.24, which looked much like the others except for a closed cockpit. One of the instructors at the Polish air force training center at Deblin, a lieutenant named Szczesny, commandeered one of two pre-production P.24s, and with the help of an armorer, installed a pair of machine guns. Thus equipped, he attached himself to the Deblin Fighter Group. Lieutenant Szczesny and the plane’s designer had every reason to be proud of the P.24; he shot down one German bomber on September 14, and bagged another on the following day.

The almost continual air bombardment and shelling by German artillery — and some of the heavier pieces had been transferred away from the west to aid in the reduction of the capital — cloaked Warsaw in a perpetual cloud of smoke through which fires could be dimly seen. Richthofen complained of “chaos over the target,” of “aircraft nearly colliding in the act of bombing.” Only rarely were German pilots able to pinpoint their assigned military targets, and the city suffered indiscriminate bombing.

By mid-month, Goering considered that the situation in Poland was such that mass transfer of Luftwaffe units back to the west for rest and refitting was indicated. One group after another was pulled out and returned to home bases in Germany, leaving Richthofen, now in charge of winding up aerial operations over Warsaw, with less than half the bombers with which the Luftwaffe began the campaign. But, as events were to prove, it was all that he needed.

On the morning of September 25, a diluted version of Operation Seaside began. First over the city were swarms of Stukas, stacked up in groups several thousand feet apart, waiting their turn in line to scream down into the cauldron below. After two hundred-plus JU.87s had flung themselves at the city, the first heavy bombers appeared. Richthofen was loath to send them in; they were not the He.111s designed for the job, but thirty JU.52s fitted out for troop-carrying missions, and therefore were without bomb racks. The cargo doors were removed and crewmen used coal shovels to scoop up the loose thermite incendiary bombs, which were sown over the city by the ton. Sortie after sortie was flown until Warsaw floated in a sea of fire. Two of the lumbering Ju.52s. were shot down by Polish flak and fell into the inferno they had created. Attempts to battle the flames had to be abandoned; the rain of high explosive, totaling five hundred tons, had smashed water mains and choked the streets with rubble that had once been proud buildings. The pyre that was Warsaw blazed brightly, the flames visible in the nighttime sky fully ten miles away.

Surrender negotiations began the following morning, and on August 27 the capitulation was made formal. With Warsaw, so fell Modlin and the diehards still holding out in the forest of Kampinoska. Thus a nation of thirty-five million was delivered into the hands of her enemies. The cost to the Wehrmacht was relatively cheap: 10,761 killed in action, including 189 pilots and air crew. The Luftwaffe lost 285 planes, mostly victims of intense ground fire during the low-level operations that had been so effective.