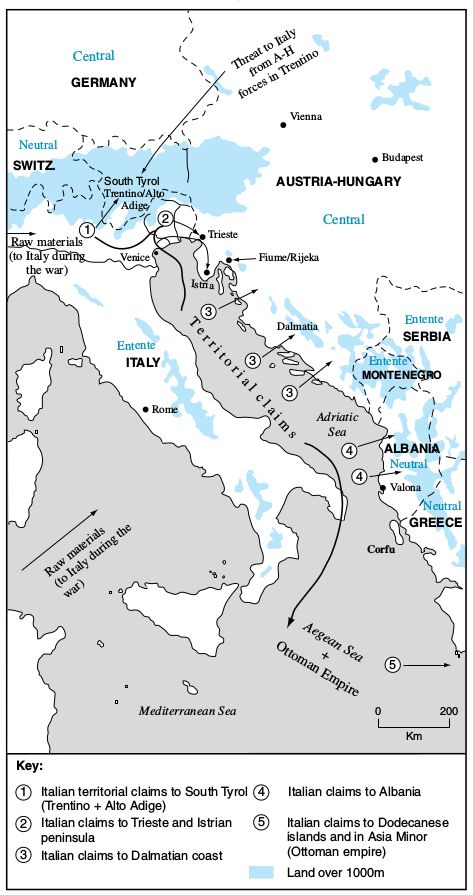

In May 1915, as war approached there were orchestrated pro-war demonstrations. On 13 May 1915, parliamentary opposition to the war led to the resignation of Salandra’s cabinet. Three days later the King re-instated Salandra when it was found impossible to appoint a neutralist administration. Salandra’s re-appointment gave him the mandate for war and, although 74 left-wing deputies opposed war, the Italian army was mobilised and war declared against Austria-Hungary on 23 May 1915 (Italy did not declare war against Germany until 1916). Once in the war, military policy passed almost entirely to the Chief of Staff, Luigi Cadorna, who led the Italian army from 1915 to 1917 on eleven costly and disastrous offensives against Austria-Hungary along the river Isonzo Map below. Italy’s lacklustre military performance in the war adversely affected her post-war efforts to secure all of the territorial demands of the Treaty of London and she finished the war feeling that she had been short-changed territorially.

From June 1915 to September 1917, Italy’s supreme commander, Luigi Cadorna, fought eleven Isonzo battles, to capture the Austro-Hungarian port of Trieste before pushing on to Vienna. He poured the bulk of Italy’s men and matériel into the attritional Isonzo battles, all fought in roughly the same area, which exceeded the western front in terms of high casualties for minimal ground gained.

The Battle of Caporetto, or the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, in October 1917 was a spectacularly successful Austro-Hungarian/German offensive against Italian forces on the upper reaches of the river Isonzo. It led to the collapse and retreat of Italian forces across the whole of north-eastern Italy. The origin of the Battle of Caporetto lay in the eleven Italian offensives led by Luigi Cadorna along the Isonzo river from May 1915 to September 1917, that threatened to break Austro-Hungarian resistance. Had Austro-Hungarian units broken, as seemed possible in August 1917, Italy could have captured the port of Trieste. Austria-Hungary appealed to Germany for help. In response, Germany sent six divisions, grouped with nine Austro-Hungarian divisions into the Fourteenth Army commanded by the German general, Otto von Below, and planning began for an assault against the Italians.

Italy’s position and conduct in the conflict were somewhat ambivalent. Although it was ostensibly an ally of both Austria-Hungary and Germany when war broke out at the end of July 1914, Italy declared its neutrality on 3 August. However, ten months later, on 23 May 1915, the Italian government abandoned this stance and declared war on Austria-Hungary – no declaration of war against Germany was issued. Subsequently, Italy and Austria conducted a vigorous but often indecisive series of battles, mainly centred upon the Austro–Italian Alpine region and the River Isonzo to the south-east towards Trieste, between June 1915 and September 1917. By the conclusion of their eleventh major battle in this area in September 1917 the Italians had forced an Austrian withdrawal, which prompted Kaiser Franz Josef to ask Kaiser Wilhelm for military assistance in the form of a counteroffensive to forestall a possible Austrian collapse. This request was initially resisted by Ludendorff, who viewed it as an unwelcome distraction; he later relented once fully apprised of the Austrians’ parlous situation. As a result, in mid-September 1917 the German Fourteenth Army was formed, comprising seven German and eight Austrian divisions, under the command of General der Infanterie Otto von Below. In addition to a number of high-quality infantry regiments and divisions, special stormtrooper units, and an abundance of artillery and other support, the Fourteenth Army included German and Austrian mountain infantry regiments, together with the requisite mountain artillery and pack animals to support them.

On 24 October 1917 German forces entered the fray in strength when the Central Powers launched a major offensive aimed at relieving the pressure on the hard-pressed Austrian forces and inflicting a significant defeat on the Italians, thereby releasing much-needed men and resources for the Western Front and elsewhere. This was the first occasion on which units of German troops were in combat against Italian forces. Although a direct response to the Austrian emperor’s request, this offensive was in many ways a logical extension of the Central Powers’ action against Serbia in October 1915, when a German army, an Austrian army and two Bulgarian armies had together overwhelmed Serbia. It also attracted some risks – it threatened to prejudice an early conclusion of the German campaign that had all but crushed Romania by 1917. In the event, the aim of the German intervention against Italy was largely accomplished: the Italian forces suffered a devastating blow at the hands of German and Austrian troops at Caporetto between 24 October and 7 November 1917. The Battle of Caporetto demonstrated the effective use by the Germans of the stormtrooper tactics and poison gas previously identified primarily with the fighting on the Western Front in France and Belgium.

Benefiting from the early morning mist that wreathed the river valleys and surrounding mountains, at 02.00 hours on 24 October, the German and Austro-Hungarian forces commenced their attack with an artillery bombardment of high-explosive, gas and smoke shells. The lack of a protracted preliminary bombardment produced complete surprise, the main assault closely following the initial artillery fire. Specialist assault troops using flamethrowers and grenades created breaches in the Italian army’s front line and infiltrated between its forward positions, where many of the defenders were badly affected by the poison gas due to the poor quality and obsolescence of their protective respirators. The stormtroopers then moved on to assault headquarters, communications sites, artillery and machine-gun positions and bunkers set behind the front line. Meanwhile the main attacking force quickly rolled over and through the Italian Second Army’s defences. So great was the surprise achieved by the attackers that virtually no Italian artillery fire was directed against them.

Even so, the fighting was particularly heavy in the centre, at the Italian strong-points of Mount Matajur and along the adjacent Colovrat and Stol ridge-lines. On the flanks the rugged terrain combined with a resolute defence by some Italian units to repel or stall the German and Austrian advance by the Tenth Army to the north-west and Second Army to the south. However, the particular success of von Below’s Fourteenth Army at the centre of the offensive allowed the Germans to strike 25 kilometres into the Italian defences by the morning of 25 October, which in turn destabilized the whole Italian line as defending units were forced to redeploy to counter this threat, simultaneously weakening their own positions. It was during the fighting at Longarone and for Mount Matajur that the then Oberleutnant Erwin Rommel, serving in the Württembergisches Gebirgs- und Schneeschuh-Bataillon with the German Alpenkorps, distinguished himself by his actions and leadership in the field, subsequently receiving the Pour le Mérite award. Although a general withdrawal was already inevitable (and the River Tagliamento offered an obvious natural line of defence), the Italian commander General Luigi Cadorna delayed this decision until 30 October, by which stage it was too late. While the Italians took some four days to cross the river, by 2 November a German division had already established a bridgehead. However, the now much-extended German and Austrian supply lines – together with the wider supply difficulties attributable to the ongoing Allied naval blockade – forced a pause in their offensive, which allowed the Italians to retreat farther, to the River Piave, by 10 November.

Despite their inability to follow through and exploit their success, Caporetto was a significant victory for the German and Austrian troops. Some 20,000 German and Austrian soldiers were killed or wounded, but no fewer than 13,000 Italians were killed, 30,000 wounded and 265,000 captured by mid-November. More tellingly, a further 350,000 Italian soldiers deserted between 24 October and 19 November 1917. A bonus of the Central Powers’ victory was the capture of 2,000 Italian mortars and at least 3,000 guns and 3,000 machine-guns during the battle.