Operation ROUNDUP

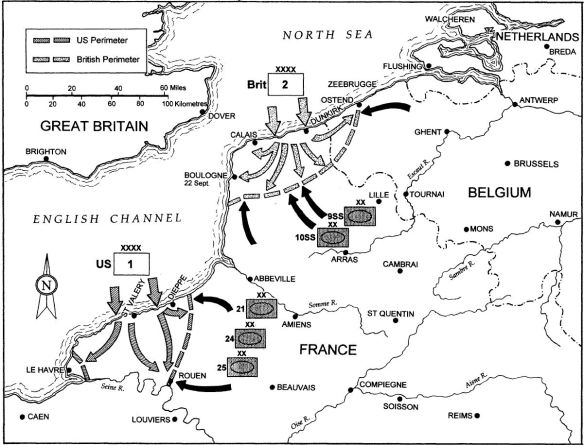

While the Germans retreated toward the Dnieper, Mountbatten and his staff finalised their plans for the cross-Channel assault, now scheduled for early September. Mountbatten’s plan called for two widely separated landings, Patton’s 1st Army near Dieppe and Montgomery’s near Dunkirk. The two armies would expand their beachhead; drive on Paris, then on toward Germany, cutting off any German forces further south. Several of the planning staff protested the landing sites, arguing that the coastal ports were too small to adequately handle the logistic and troop build-up, that autumn storms could disrupt the transfer, and most importantly, that the two armies were too far apart to support one another. With Eisenhower’s (and Marshall’s) support, however, the plan was approved. The landings would take place under an air umbrella from Britain and the troops would be closest to their ultimate goal, Germany. His Dieppe raid had shown Mountbatten that Hitler’s Atlantic Wall was nearly all fiction.

Montgomery’s 2nd Army would open channel ports from Boulogne to Ostende. His plans called for the British 3rd and 15th Divisions to directly assault Dunkirk (GOLD beach) while the 43rd landed beside them on SWORD beach. The Guards Armoured Division and 49th Division would follow up the landings. In the wings the Canadian 1st Army waited. The Commonwealth’s primary post-landing target: the Dutch port of Antwerp. Patton’s 1st Army would revisit Dieppe with the 1st Division and 4th Divisions landing on OMAHA and UTAH beaches, respectively The US 2nd Armored and 2nd Infantry would follow up the assaults. Patton’s initial targets: Dieppe itself and La Havre, and expanding between the Somme and Seine Rivers to take Rouen and Amiens. De Gaulle’s Free French 2nd Armoured Division along with nine other US infantry and four US armoured divisions remained in reserve for subsequent operations in the direction of Paris.

Facing them were something over forty divisions, operating under the Commander in Chief-West, Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstadt. Their immediate opponent was the German 15th Army which had responsibility for the French coast around Pas de Calais. The army had recently switched commanders, with Colonel-General Hans von Salmuth arriving from the Eastern Front to take command in early August. He inherited defences that were still being built. Allied Intelligence pinpointed most of the Salmuth’s divisions and assessed them as weak, undermanned, and underequipped. The rebuilding Panzer divisions, including the 24th at Le Mans and 21st near Caen, generated most of the concern but Mountbatten felt strongly that air power would delay them long enough to allow the beachheads to develop and get Allied armour ashore. Intelligence, unfortunately, missed several key units. In particular, the 25th Panzer at Beauvais and the 10th SS Panzer Division at St. Quentin had not been located, nor the extent of Rommel’s buildup in Northern Italy, which included two rebuilding Panzer divisions from Tunisia and the 17th SS Panzer Division.

After a week’s delay due to bad weather, ROUNDUP’S D-Day began the night of 15 September 1943, with the dropping of the British 1st Airborne and the US 101st Airborne into France behind the landing beaches. The drops went poorly, as transport crews had no real experience with large-scale paradrops. Both divisions were scattered badly, losing much of their cohesion and fighting power. However, both units were able to achieve significant gains. The British, landing miles behind their intended drop zones, took the town of Lille, while the 101st fought their way into Dieppe against the 348th Division. The initial fighting began to show that the Germans had learned lessons from the raid on Dieppe – the fortifications were heavier and better-sited for all-around defence.

Royal Navy and US Navy ships opened fire as dawn broke on their targeted beaches in an intense barrage to prepare the way for the troops. In the skies above both air forces kept the Luftwaffe at bay. In all the landings went fairly well.

The US 1st Division landed successfully at OMAHA beach without heavy casualties, aided by the battle the Germans were fighting with the 101st. Trouble arrived as the 2nd Armored Division began to follow up – they found the beaches restrictive and armour had a problem getting off. On UTAH beach the 4th Division had a much harder time smashing through the defences of the 245th Division, but managed to push them back enough to get start landing the 2nd Infantry Division and 1st Army Headquarters.

At the SWORD beaches, two British divisions had a savage fight to take Dunkirk from the 18th Luftwaffe Field division, but with the aid of the specialised armour, took the town and began the process of landing the Guards Armoured Division. To west, fighting on GOLD beach bled the 43rd Division white due to heavy counter-attacks coming out of Calais, but the beachhead held long enough to get the 49th Division ashore and into line.

German reaction showed that Dieppe’s lesson of slow response had been learned as well. Mobile units, especially artillery, arrived to take the beachheads under fire. Lille was retaken after four days of fighting, delaying the 10th SS Panzer Division’s movement toward Dunkirk. Other mobile divisions began their move as well – pre-D-Day bombing had been insufficient to seriously disrupt France’s well developed transportation net.

Both the US and British beachheads began to expand outward, but ran into serious opposition. The Germans repulsed 2nd Infantry Division’s assault on Le Havre with heavy casualties; 2nd Armored and 4th Infantry pushed their way into Rouen, while the 1st Division secured Dieppe against scattered counter-attacks. Mountbatten delayed additional US armoured units to allow more infantry to land. The first British attack on Calais failed, although the Guards Armoured overran one German training division en route to the port. To the east, the Belgian port of Ostende fell to the 15th Division. The Canadian 2nd and 3rd Divisions landed to replace the battered assault divisions. Bad weather and Luftwaffe attacks delayed reinforcement on the beaches. The air battle claimed more and more aircraft, with the Allied effort hurt by their limited time over the battlefield flying in from Britain.

Rommel arrived from Northern Italy four days after the landings to assume command of the German reaction. Under his energetic leadership, German armour began a series of concerted attacks on the beachheads. The 9th and 10th SS Panzers made an assault on the Guards Armoured that ended in stalemate with heavy losses to both sides. Armoured forces backed up German infantry to retake Ostende, threatening the western flank of the British beaches. The 12th SS Panzer struck at Dieppe, almost carrying the town, but was destroyed as was the defending 1st Division. Only timely reinforcement by the 8th Infantry Division held the town. Rouen changed hands as the 25th Panzer caught the 2nd Armored overextended and scattered their supporting 4th Division infantry. Patton was killed as he moved forward to rally his troops.

The Canadians moved forward to support the growing battle with the two SS panzer divisions, while the 7th Armored and 50th Divisions landed to capture Calais that had been cut off. The British held their own against the counter-attacks but could not advance. Luftwaffe bombers created havoc on the Allied supply situation.

On 1 October, 1943, disaster struck as two panzer divisions, the 21st and 24th, launched a heavy assault on Dieppe and the 8th Infantry line collapsed. Only the newly landed Free French 2nd Division and naval bombardment held the panzers away from the US beaches, as more German troops arrived. In the plains behind Dunkirk and Calais British and German forces continued their savage stalemate, each suffering heavy casualties, with the 10th SS and the Guards Armoured Divisions virtually annihilated.

The crisis at the US beaches forced a decision on Mountbatten and his staff. They found that the chosen beaches were too restricted to allow a continuous flow of troops and supplies, especially in the US sector, due to bad weather and Luftwaffe attacks. They were also unable to completely disrupt the flow of German mobile units to the battlefields and those units were far more effective than previously estimated, ULTRA intercepts let them know that substantial reinforcements were in the way from Italy – the Allied forces remaining in the Mediterranean were unable to take advantage of the redeployment. Newly arrived 1st Army commander Hodges, who took over when Patton was killed, estimated he could only hold for another week against Rommel unless more troops and armour arrived. At Dunkirk, Royal Engineers worked frantically to get captured ports into operation to ease supply problems that Montgomery faced. He held his own but was suffering heavy casualties. Eisenhower knew, however, that collapse of the US beachhead would release more German divisions to hit the British.

Mountbatten made the hard decision to withdraw from France. German pressure stayed heavy as the troops came off. The free French division declined to be withdrawn and died protecting the beachhead as a rearguard. By 20 October the last troops had been taken off, completing the disaster. In all, three armoured divisions, and ten infantry divisions had been virtually destroyed, over 100,000 casualties and masses of equipment. In return they had smashed eight smaller static divisions on the French coast and burned out six German panzer divisions.

The Allied withdrawal from France had a horrific effect on the Allies. The British criticised the US troops and leadership that had forced them into a premature invasion. The US became equally adamant that the fault lay with British that had landed them in wholly inadequate beaches. Both Mountbatten and Eisenhower were sacked; Montgomery infuriated the US even further declaring he knew the Dieppe landings were going to be a disaster all along.

The truth, of course, lay in between. The Germans had learned their lesson’s from the 1942 Dieppe raid better than the Allies and had prepared better counter-attack plans. Especially damaging was the inability of the Allied air forces to keep the Luftwaffe from hammering the supply ports – all the more so, since the British had learned that lesson in their 1940 Norwegian debacle.

In the midst of the discussions, a major change occurred within the British Government; aided by the cross-Channel disaster, Churchill’s opponents, able to gather their strength and armed with ‘one disaster too many’ ousted the Prime Minister. Lord Halifax, recalled from his post as ambassador to the United States, formed an interim government.

Stalin reacted with even more anger than Churchill’s opponents. The Soviets had suffered massive casualties in the Orel offensives and several attempts to penetrate the German defences on the Panther-Wotan line.13 With the withdrawal of the Western Allies from their bloody beaches in France, Stalin knew that Hitler could now substantially reinforce his forces in the East since the threat of another Allied invasion was virtually nil for at least six months to a year. Stalin did the only thing he could and directed Molotov to begin making peace-feelers through Sweden.

The news of an impending Russo-German truce struck the Allies like a bombshell. With the Soviet Union out of the war, there was little hope of Anglo-American forces alone defeating Germany on the Continent. Admiral King took advantage of the iron logic of the situation and of a depressed Marshall to gain approval for a major US shift toward the Pacific.

The Third Reich would survive a few more years.

The Reality

In reality, two ships from Operation HARPOON made it to Malta in June 1942, landing some 15,000 tons of supplies. That made it possible for the Maltese to endure until Operation PEDESTAL fought through to the island in August. They suffered terrible losses despite a powerful Royal Navy escort.

It might be counterintuitive that Malta’s surrender would not have helped Rommel very much, but when the island capitulates in our story, Rommel had advanced already into Egypt and his supply line became then a matter of arithmetic. He needed something like 110,000 tons of supply a month. Tobruk could handle, at most, 20,000 tons – the rest had to come from Tripoli and the Axis simply did not have that many trucks. Factor in Allied bombing and you get a DAK with a lousy logistics picture.

The strategic arguments between the British and American Chiefs of staff are very real. The British came to the conferences well prepared, and, with Roosevelt wanting to get troops into action, Marshall had to capitulate. He did however slow troops crossing to England as a result, making it virtually impossible to mount ROUNDUP in 1943. The delay in a Second Front angered Stalin, but new information appears to indicate he expected it and used the anger as a political bargaining chip. Most historians (for example, Dunn 1980) who believe the Allied shouldn’t have dabbled in the Mediterranean, believe that the Soviets were able to occupy most of East Europe as a result.

Hitler, of course, did very little reassessing of his decisions, leaving far more Axis troops in Tunisia to be trapped than allowed here. Rommel did have doubts about attacking at the end of August 1942 at Alam Haifa, but did anyway, giving in to his boss’s demands for the Nile and his own desire to reestablish ascendancy over the 8th Army. Hitler’s decision to form an Eastern Wall also came far too late to do more that delay the Soviets.

The plans for ROUNDUP came from the original preliminary plans drawn up during the aforementioned Allied debate. All of the objections put forth on the plan were real, but the plan never got past the ‘here’s what we want to do’ phase, as the Mediterranean focus stayed in place. The BRIMSTONE plan against Sardinia had been drawn up as an option following the invasion of Sicily.

Finally, the raid at Dieppe failed badly with almost sixty-six per cent of the Canadians involved killed or captured. The small convoy intercepted above in actuality had been detected but that information was not passed on to the raiders. Third Commando’s convoy ran into them, delaying their assault and alerting the Germans. The minimal support described above is real, as was the final plan for a frontal assault on the port. The original plan called for a pincer assault and might have had a better chance for success. Churchill’s comment that changed the plan above was actually made in the 1950s as he was writing his memoirs. There is still a lively debate on exactly why Dieppe was attempted with such a ridiculous plan.

Bibliography

Bradford, Ernie, Siege Malta: 1940-1943, New York: Wm Morrow & Company, 1986.

Bruce George, Second Front Now! The Road to D-Day, London: MacDonald & Janes, 1979.

Dunn, Walter Scott, Jr, Second Front Now 1943, Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 1980.

Eisenhower, John S. D., Allies: Pearl Harbor to D-Day, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1982.

Glantz, David and Jonathan M. House, The Battle of Kursk, Lawrence, KS: The University Press of Kansas, 1999.

Harrison, Gordon A., Cross Channel Attack, Washington, DC: Center for Military History, 1951.

Levine, Alan J., The War against Rommel’s Supply Lines, 1942-1943, Westport, CT: Praeger, 1999.

Perowne, Stewart, The Siege within the Walls: Malta 1940-1943. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970.

Pogue, Forrest C, George C. Marshall: Organizer of Victory, 1943-1945. New York, Viking Press, 1973.

Van Creveld, Martin, Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Villa, Brian Loring, Unauthorized Action: Mountbatten and the Dieppe Raid, New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.