The story of the Hundred Years War is in many ways that of the professional versus the amateur, with the increasing professionalization of English armies followed, usually all too late, by those of France. By the time of Edward I, the English military system, a fusion of the pre-Conquest Anglo-Saxon military organization with Norman feudalism, was beginning to creak. The Anglo-Saxons had depended on semi-professional household troops employed directly by the king and supported by the fyrd or militia, a part-time force which was embodied when danger threatened and could be required either to operate solely within its own shire or, like those elements which accompanied King Harold to Stamford Bridge and down again to Hastings in 1066, nationwide. The Norman feudal system depended on the notion that all land belonged to the king and was granted to his supporters, who in turn owed him military service. This service was expressed in terms of the number of knights the landholder, or tenant-in-chief, was required to provide for a fixed time, usually forty days. Often the tenant-in-chief would sub-allocate land to his tenants, who then took on the military service obligation. Each knight was required to provide his own equipment – armour (initially mail, giving way progressively to plate), helmet, sword, shield and lance – and at least one horse. Each knight brought his own retinue with him: a page to look after and clean his armour, a groom to care for his horses, and probably a manservant to look after him. Often there would be numerous armed followers, frequently described as esquires, or well-bred young men aspiring to knighthood. Bishops and monasteries also had a military obligation, usually, but not always, commuted for a cash payment in lieu. The number of knights required for each land holding fell steadily during the post-Conquest period, presumably because knights and their equipment became more expensive, and by 1217 a total of 115 tenants-in-chief are recorded as producing between them 470 knights.

When Edward III came to the throne, the English peerage had not developed into the modern system of baron, viscount, earl, marquis and duke. It was Edward himself who created the first English duke – his eldest son, the Prince of Wales. After the Conquest, the Normans took over the existing Anglo-Saxon title of earl (from the Scandinavian jarl), although it was given to Normans and not to those who held the rank before the Conquest; and William I introduced the rank of baron, which came below an earl. The term ‘knight’ did not have the exactitude that it does today, when we have two types of knight: the knight bachelor, who is dubbed by the monarch and entitled to be described as Sir Thomas Molesworth and his wife as Lady Molesworth, and who holds the title for his lifetime only; and the hereditary knight baronet, also entitled to be described as Sir Thomas but with the abbreviation ‘Bart.’ or ‘Bt.’ after the name. The latter honour is relatively recent, having been introduced by King James I as a money-raising scheme in 1611.

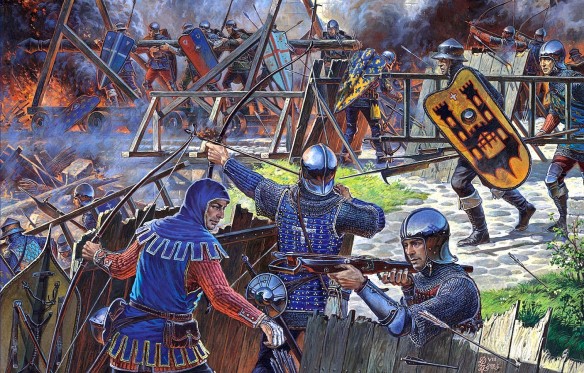

During the medieval period, the honours system was much more elastic. A military knight had not necessarily been dubbed but was able to afford the cost of knight’s equipment and was probably a landholder. Assuming that he did reasonably well, he would almost certainly be dubbed eventually, often on the eve of battle. A knighthood banneret, a title that lapsed in the seventeenth century, could only be awarded on the field of battle and only if the king was present; it entitled the holder to display a rectangular banneret, as opposed to the triangular pennon of lower-ranking knights, and his own coat of arms or heraldic device. The men who filled the knightly class were brought up and trained for battle, but it was battle as individuals – tourneys and jousts for real, if you will – and under the feudal system there was real difficulty in getting them to act as a team or to persuade them to adopt a common tactical doctrine. The knights – whether dubbed or not – were what we would call the officers of the army, while the Other Ranks were provided by commissions of array, or conscription from able-bodied men of the hundreds or shires. Again, these were only required to serve for a limited period, and there were frequent arguments over whether or not they could be compelled to serve outside their own locality, and whether it was a local or national (that is, royal) responsibility to feed and pay them.

When the king knew personally all or most of the landholders in the kingdom, the feudal military system worked reasonably well. It sufficed for dynastic squabbles and raids from Scotland, but, as time went on, it could not cope with expeditions abroad or with sieges that lasted more than forty days, nor could it provide permanent garrisons. Men could not reasonably be expected to be absent from their homes during the planting season, nor for the harvest, and this greatly restricted the scope and duration of any military campaign. Even as early as the reign of Henry II, in 1171, the king faced his rebellious sons with forces that, while largely composed of men carrying out their feudal dues, included ‘knights serving for wages’. Given that English kings would increasingly fight their wars abroad, mainly in France or in Scotland, and that soldiers would be required to be away from home for far longer than the feudal system allowed, the transition from a feudal host, where the officers served as part of their obligation to their overlord, to an army where all served for pay was an inevitable progression. Once soldiers (of any rank) serve for pay, rather than almost as a favour, they can be ordered to arm themselves and fight in a certain way; they can be sent to where the king wants them rather than where they want to go or not go; and, as long as the money holds out, loyalty is assured. It was Edward I who began this professionalization of the army, and eventually he paid everybody except those whom we would term generals. It was his efforts that laid the groundwork for the great victories of his grandson Edward III, against French armies which were usually far larger but still raised under a semi-feudal system.

One way of raising soldiers, once the feudal system had irreparably broken down, was to hire foreign mercenaries, and there were lots of these ready to sell their services to the highest bidder. Most of the mercenary bands were from areas where nothing much grew, like Brittany; or where there was overcrowding, such as Flanders or Brabant; or where other career paths were limited, as they were in Genoa. The difficulty was an inherent English dislike of foreigners (some things don’t change), so, while there were contingents from Brittany and Flanders in English armies abroad, there were very few actually employed in England. Even the Welsh, who provided large numbers of soldiers for Edward’s wars, tended to be mustered and then marched off to the embarkation ports as speedily as possible.

It was not only the move from feudal to paid service that marked a revolution in military affairs, at least in England, but the composition of armies too. During the feudal period, the major arm was the heavy cavalry, composed of armoured knights on armoured horses who provided shock action and could generally ride through and scatter any footmen in their way. As socially the cavalry were regarded as several cuts above the infantry, who were often a poorly equipped and scantily trained militia, this held true for a very long time. The cavalryman wore mail or latterly plate armour, carried a sword, lance and shield, and was mounted on either a destrier or a courser. The destrier, or great horse, was not, as is sometimes alleged, the Shire horse or the Percheron of today. Rather, it was similar to today’s Irish Draught: short-coupled, rather cobby, with strong quarters and well up to weight, the destrier was probably between fourteen and fifteen hands, although some of the horse armour at the Royal Armouries at Leeds is made for a horse of fifteen to sixteen hands. The courser was similar, but lighter and cheaper. Destriers are sometimes said to have been entires, and the Bayeux Tapestry certainly shows them as uncastrated, but this seems unlikely. An uncastrated horse is far less tractable than a gelding or a mare, and the depiction of the complete animal in paintings and tapestries of the period may simply be symbolic – our horses are male and rampant, and so are we.

There has been much discussion of the role of the stirrup in equestrian warfare. Some authorities state that it was only with the invention of the stirrup that the cavalryman could be anything other than an appendage to an army: useful for reconnaissance and communications but incapable of serious fighting, because only when able to brace against the stirrups could a man deliver a weighty blow without falling off. It is probable that those who make this assertion have little experience of riding. While the stirrup is a useful aid to balance when the horse does something unintended and unexpected, it is by no means essential and it would have been very difficult to fall out of a stirrupless Roman saddle, with its high pommel and cantle. Similarly, the armchair nature of the medieval saddle, with or without stirrups, made for a very safe seat except if the horse fell, when the rider, rather than being thrown clear as he would hope to be in a modern saddle, would be trapped under the horse, risking a broken pelvis or his throat being cut by an opportunistic infantryman. All the depictions of the armoured medieval cavalryman show him riding with a straight leg and very long leathers, so he could not brace against the stirrups in any case. It seems that the usefulness of the stirrup was in mounting the horse when there was no mounting block available or when the weight of armour made it impossible to vault astride the withers.

In addition to his warhorse, the armoured warrior would also have a palfrey, a hack to be ridden when not in battle and not encumbered by armour, and a packhorse to carry his kit. Fodder for a minimum of three horses per man and rations for him and the host of camp-followers, to say nothing of the cost of horses and armour, made the armoured knight a very expensive fellow, but it was not cost that forced his decline and eventual banishment from the battlefield altogether, but advances in technology and the quality of the infantry.

During the Welsh wars, the English began to have doubts about the merits of an army composed mainly of heavy cavalry: the hills and valleys of Wales did not lend themselves to flat-out charges or to wide envelopment, and the Welsh infantry spearman was generally able to put up a stout defence unless surprised and scattered. There were other pointers: at Courtrai in 1302, a Flemish infantry army had roundly defeated the flower of the French heavy cavalry by digging ditches across the approaches to their position and then standing on the defensive. The French duly charged, the impetus was destroyed by horses falling into or breaking legs in the ditches, and the Flemish won the day. As far as the English were concerned, it was Bannockburn that began to bring it home to thinking soldiers that well-organized and equipped infantry, however ill-bred, could see off the mounted host if they could bring their enemy to battle on ground of their choosing. There, on 23 June 1314, Robert Bruce’s Scottish army took up a dismounted position at one end of a flat field, with both his flanks protected by woods and marshes. His men dug holes and ditches, three feet deep by three feet wide, across the inviting approaches, camouflaged them with wooden trellises covered with grass and leaves, and waited. Having had his vanguard repulsed on that day while trying to move round the Scottish flank to reach Stirling and relieve its siege, Edward II ordered, as expected, a cavalry charge on 24 June. It was a disaster. The Scots infantry did not flee, and by presenting a wall of pikes they prevented even those horsemen who did negotiate the obstacles from getting anywhere near them. Eight years later, Sir Andrew Harcla’s wedge of pikemen supported by archers stopped Thomas of Lancaster’s infantry and cavalry getting across the only bridge over the River Ure at Boroughbridge, while an attempt to put cavalry across by a nearby ford was stopped by archers alone.

Very few radical advances in tactics come all at once or are the product of one commander’s thinking. The shift towards reliance on infantry in England and Scotland was not a sudden one but a product of experimentation and discussion at home and abroad. Many Scots took service as mercenaries in Europe and would have brought home ideas from Flanders, and the costs of the mounted arm would have forced rulers to consider cheaper alternatives. But there can be little doubt that the rout of Bannockburn accelerated English thinking, while skirmishes at home gave scope for trying out various combinations of archer, horse and foot.

That the English had absorbed the lessons of Bannockburn and Boroughbridge was duly confirmed at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill. At Dupplin Moor, six miles south-west of Perth, on 11 August 1332, the 1,500-strong army of the Disinherited – nominally commanded by Edward Balliol but with English advisers there with the unofficial blessing of Edward III – defeated the Bruce army of 3,000 commanded by Donald, earl of Mar. The Disinherited lost two English knights and thirty-three men-at-arms. The Scots losses are unknown but included three earls and must have been many hundreds. On 19 July the following year at Halidon Hill, two miles north-west of Berwick-upon-Tweed, an English army of around 4,000 led by Edward III in person roundly defeated Sir Archibald Douglas’s 5,000-strong Scots army. Again, English losses were negligible – one knight, one esquire and ten infantrymen of various sorts – while Douglas and five Scots earls were killed and an unknown number of lesser nobles and soldiers, perhaps as many as 1,000 all told. After Halidon Hill, there was no one left in Scotland capable of raising an army and Robert Bruce’s kingdom was effectively at an end.

Both Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill had a number of factors in common which enabled English armies to inflict crushing defeats on greater numbers, and those factors were to be incorporated in English military doctrine for the Hundred Years War. In each case, archers formed the largest portion of the armies and the victorious commanders chose to stand on a piece of ground where their own flanks were secure and which restricted the frontage of the enemy. At Dupplin Moor, the Disinherited took up a defensive position at the head of a steep-sided valley, while at Halidon Hill Edward’s right flank was covered by the sea and on his left was marshy ground with a river flowing through it. In both cases, English forces fought on foot, including Edward himself at Halidon Hill, in two ranks with archers on the flanks, and in both cases the archers concentrated their arrow storms on the advancing Scots flanks, forcing them to close in towards their centre and reducing their frontage and hence their shock effect still more. By the time the Scots finally reached the English infantry line (or failed to do so at Halidon Hill), they had suffered so many casualties from the archers that their cohesion was broken and they were repulsed and fled. The pursuit was taken up by the English remounting their horses and following the defeated Scots. The policy of dismounting and standing on the defensive on carefully chosen ground, using archers to prevent outflanking moves and to break up enemy attacking formations, and presenting a solid mass of infantry in a two- or four-deep line to meet the attacking remnants was the recipe for the great English victories of the war. It was only when the English overreached themselves, and the French finally began to learn from their own defeats, that English military supremacy began to wane.

Technology came in the shape of the longbow. Bows and arrows are as old as prehistoric man: simple missile weapons, they are depicted in Palaeolithic and Neolithic cave paintings, and archaeological excavations have uncovered bows and arrows dating back to the third millennium BC.8 Bows were in use by Roman auxiliaries and light hunting bows were used by both sides at Hastings in 1066. Quite how and where the short bow, drawn back to the chest and with its limited range and penetrating power, mutated into the English longbow is uncertain: it would not have been a sudden change, and the longbow may have first been used by the southern Welsh in the second half of the twelfth century, although the evidence is scanty. It was anyway gradually, and eventually enthusiastically, adopted by the English, and, as a reluctance to spend money on defence is not confined to twenty-first-century British governments, its cheapness would have appealed. The longbow would become the English weapon of mass destruction; it was consistently ignored by England’s enemies, who would consistently be slaughtered by it. From the time of Edward I’s Assize of Arms in 1285, all free men were required to keep weapons at home and to practise archery regularly at the village butts, for the longbow was not something that could be picked up and used by anybody. Rather like Scottish pipers, archers began to develop their skills as children, gradually increasing the size and ‘pull’ of their bows as they grew up. Exhumed bodies of medieval archers show greatly developed, or over-developed, shoulder and back muscles.

The standard longbow was made of yew wood, either native English yew or imported from Ireland, Spain or Italy, and approximated in length to the height of the archer. Thus, there would not have been very many that were six feet in length, as modern reproductions are. Rather, the average would have been around five feet two or three. While originally the same craftsman would manufacture bows and arrows, this soon diverged into two trades, the bowyers who made bows and the fletchers who made arrows, each with their own guild. The bow had a pull of around 100 pounds and shot a ‘cloth yard’ arrow out to an effective range of about 300 yards. There is dispute over exactly how long a cloth yard was, the measurement being one used by Flemish weavers, many of whom were encouraged to come to England by Edward III. Definitions vary from 27¼ to 37 inches, the latter supposedly codified by Edward VI, the short-lived son of Henry VIII, while some sources describe an arrow as being an ell in length. As an English ell was 45 inches, this seems unlikely. Whatever the length of the arrow – and the shorter seems more realistic – its construction was a skilled affair, requiring the fletcher to obtain good straight wood for the shaft, usually ash, to cut it to the correct length, and to affix the arrowhead and the feathers to stabilize the arrow in flight. Three pinion feathers per arrow were required and generally came from a goose. As a goose only had six feathers that were suitable, three on each wing, which regrew annually, and as many hundreds of thousands of arrows were ordered during the wars, the goose population in the kingdom must have been considerable.

Arrowheads came in two basic types: one to pierce flesh with broad barbs; the other, much narrower with a sharp point and no barbs, to penetrate armour. While the arrow was said to be capable of going through an inch of oak at a hundred yards, it would not have gone through plate armour except at relatively close range and at a flat trajectory. The usual way of employing archers was to mass them and have them shoot volleys at a 45-degree angle, thus obtaining maximum range and ensuring that they struck from above. While this might not immediately kill armoured cavalrymen, it would wound them, panic their horses and generally discourage an enemy from pressing home his charge. As a competent archer was expected to be able to discharge ten arrows a minute, the 5,000 or so archers that Henry V had at Agincourt in 1415 could produce a horrifying arrow storm of 25,000 arrows every thirty seconds.

The other missile weapon in general use was the crossbow. This was made of a composite of wood and horn, and even steel, and shot a bolt, or quarrel, of iron, steel or ash with more force to a greater range and with more accuracy than the longbow; but the effort and the length of time needed to pull the bowstring back to engage with the trigger meant that its rate of discharge was only around two quarrels a minute. The English generally only employed the crossbow as a defensive weapon in castles and fortified places. It could, however, be shot from behind cover, unlike the longbow, and unlike the longbow required little training to use. In the field, crossbowmen carried a large shield, a pavise. As tall as a man and with an easel-type leg at the back allowing it to stand up unsupported, this afforded the crossbowman cover while he reloaded. The French did have some longbowmen but presumably considered the training and development not to be worth the effort. Still fighting their wars with a feudal host, they employed large numbers of mercenary crossbowmen, to their detriment as we shall see.