Defeat brings dismissal, open or disguised, as the recent careers of Nivelle, Gough, Murray, Cadorna and Falkenhayn illustrated. Now, failure in Italy ended Conrad’s career; Emperor Charles relieved his most experienced general of his command on 14 July, replacing him by the Habsburg professional soldier, Archduke Joseph. A month previously, among the French on the Western Front, the axe had fallen, too. Clemenceau’s first victim, understandably, was General Duchene of the Sixth Army on the Aisne. He was also tempted to make Pétain a scapegoat for having failed to anticipate the German drive back to the Marne. But he had no faith in any of the corps commanders as a successor to Pétain. Instead, on 6 June, he decided to recall Guillaumat from Salonika and appoint him Military Governor of Paris, ready to take over from Pétain as Commander-in-Chief should the ‘saviour of Verdun’ fail to rise above the defeatism which seemed often to envelop him. To fill the vacancy in command of the Allied Armies of the Orient, Clemenceau turned at once to Franchet d’Esperey. Six months previously Franchet had declined the post. But now he was himself under a cloud, since it was his Army Group North which was thrown into retreat by the initial attack of 27 May on the Chemin des Dames. Pétain could stay; for Clemenceau astutely judged that Franchet’s removal would placate critics among the parliamentary Deputies.

The order to set out for Salonika reached Franchet at his headquarters in Provins on the afternoon of Thursday 6 June. He was received by Clemenceau at the Rue St Dominique next morning; it was a frigidly correct meeting. On the next Tuesday evening he left the Gare de Lyon for Rome and Brindisi. Somewhere south of Dijon, in the small hours of the morning, his train passed the express bringing Guillaumat back to Paris. He reached Salonika the following Tuesday afternoon, 18 June. A group of senior officers greeted their new commander at the railway station. But he was no man for social pleasantry: ‘J’attends de vous une inergie farouche’ (I expect from you ferocious vigour’), he told them bluntly. ‘Seems a smart looking little man’, General Milne noted noncommittally in his diary.

In some respects Franchet d’Esperey’s transference to Salonika resembles Allenby’s experience the previous June. While neither general had ‘failed’ on the Western Front, each fell short of expectations raised by former successes. Each projected a forceful character, seeking to conceal sorrow at the loss in battle of an only son, Franchet’s at Verdun, Allenby’s in Flanders. Both generals, though scrupulously loyal, were critical of their commanders in France: Allenby mistrusted Haig’s plans for the Ypres Salient; and Franchet never became reconciled to what a senior British soldier called ‘Boche killing’. A few hours before leaving Paris for Salonika, Franchet told a friend: ‘I am not angry at being sent there, as I don’t approve of the Foch-Pétain way of doing things. It will certainly defeat the Boche, but at the cost of men, of time and of money. These fine fellows [Ces braves gens] have no imagination’. Yet there were two important differences between their assumption of the new commands: while Allenby knew little of Palestine in modern times, Franchet was familiar with the Balkans and had preconceived ideas on the strategy he should follow; and, while Allenby’s Prime Minister had given him a definite objective within a definite time limit before he left London, neither Clemenceau nor Foch provided Franchet with military or political instructions of any form. His only order was to leave for Salonika ‘as soon as you can’.

Allenby had benefited from Murray’s legacy of railway and water-pipeline constructions and from Chetwode’s considered reflections after the first two battles of Gaza. Franchet d’Esperey inherited abortive projects put forward by Sarrail’s staff during 1917 and an operational plan drawn up by Guillaumat in March 1918, providing for a limited offensive up the Vardar valley, between the river and Lake Doiran. He was not attracted by any proposal put before him; each was too restricted in scope, and there was no touch of originality or surprise about them. More to his liking was a scheme put forward by the Serbian Chief of Staff, Zivojin Misic, the general whose First Army scaled the ‘butter churn’ mountain, Kajmakcalan, nearly two years before. Misic had won the support of Prince-Regent Alexander of Serbia for another assault on the mountain chain along the Greek-Serbian frontier, believing that it would be possible to break the Bulgarian defensive line and force the enemy back across the Vardar and into Bulgaria proper.

Ten days after arriving in Salonika, Franchet accompanied Prince Alexander and Migie to the Serbian headquarters, eighty-five miles north-west of Salonika, in a clearing among the fir trees 5,500 feet up in the Moglena Mountains, beyond Kajmakcalan. Next day they climbed higher still, another 2,000 feet up to a Serbian observation post hewn in the rock. From this eyrie it was possible to see, four miles away, the Bulgarian defensive system, running along the formless ridge known as the Dobropolje. Behind this line of bare summits was a slightly higher peak, the Kozyak, three miles to the north and included by the Bulgarians in their second line of defence. Beyond the crests of the mountains bridle paths and goat tracks led down to valleys which ran towards the upper Vardar, along the natural line of advance for any army seeking to turn the enemy’s position and move forward up the main route towards the Danube and the distant goal of the central European plains. The mountain barrier was formidable, the peaks not so high as Kajmakcalan but steeper and forming a broader chain, militarily deeper in defensive depth; the Serbs had planned an attack on the Dobropolje as part of Sarrail’s stillborn offensive in the spring of 1917 but had succeeded in capturing only a few outposts among the foothills. Thereafter both Sarrail and Guillaumat dismissed the prospect of making any advance through this region; the mountains seemed unassailable. Franchet, too, hesitated — but for less than twenty-four hours. The enemy would never expect an attack here and might be caught off-balance by a surprise assault. He could see around him evidence of the skill of the Serbs as mountain fighters; he was impressed by their eagerness and by the volunteers in the Yugoslav Division, who had made a journey halfway round the world to fling themselves into the battle. On 30 June he let Misic and Prince Alexander know that he favoured a major attack in this sector of the Front; the whole Serbian Army would go forward and would be supported by two French divisions, placed under the command of Misic in the field. A week later Franchet’s staff had completed their first draft survey of the projected offensive. Hundreds of navvies — Italians and displaced Russians as well as local Greeks and Albanians — were engaged to open up approach routes to the Moglena Mountains. Enemy Intelligence was, in the early stages, deceived into believing that the principal task of these labourers was to improve communications with Albania’s Adriatic harbours.

Franchet d’Esperey did not receive his formal directive from the Ministry of War in Paris until the day after his return from Serbian advanced headquarters. His orders, approved by Clemenceau, prescribed a series of local actions, designed to weaken Bulgarian resistance preparatory to a major offensive in the autumn, which would relieve pressure on the Western Front. But Franchet did not seek merely local gains: they needlessly cost lives and wasted material. His intention was to build up the Serbian and Greek forces before striking hard and swiftly to break the Bulgarian defences and knock aside the weakest of Germany’s props. Once that was achieved he could implement that grand design he had outlined to Poincaré during the first months of war, the thrust deep into the heart of Europe.

Lloyd George, once inspired by a similar strategic vision, now showed little interest in Salonika. The Balkans were not on the War Cabinet’s agenda. The 13th Black Watch had sailed from Salonika for Taranto and the train to France two days before Franchet’s arrival, and even as late as the last week in July the CIGs urged the War Cabinet to withdraw all British regiments from Macedonia and replace them with Indian troops. When the Supreme War Council met at Versailles on 2 July the Prime Minister complained to Clemenceau that he had not been consulted over Franchet d’Esperey’s appointment; why, he wished to know, were the French contemplating an offensive in a theatre of operations where the Council had resolved to stand on the defensive? Clemenceau was disarmingly frank: he reminded Lloyd George that he personally always opposed Balkan expeditions and more than once wanted the whole Allied force brought back from Salonika; he would never allow an attack to be made in Macedonia that ‘would weaken the strength of the Allies on any other Front’.

Clemenceau was not being evasive; at such a critical moment for the armies in France he remained supremely uninterested in Franchet d’Esperey’s movements. Over the next two months the staunchest advocate of the Salonika armies was their old commander, General Guillaumat, who became French Military Representative on the Supreme War Council in the second week of July.

The British remained sceptical. The ‘smart looking little man’ handled Milne badly; for the British commander, though by far the longest-serving general in Salonika, was not consulted over Franchet’s proposed offensive. He received the draft general plan on 25 July and found that his staff was expected to develop operational details for the XII and XVI Corps around Lake Doiran and also for six Greek divisions under his command. In the hills above Doiran the Bulgarians had the advantage in numbers and in firepower. Milne would have preferred an advance up the River Struma to the Rupel Pass, a natural route through the fruit-growing region around Kustendil and on to the capital, Sofia. One wonders why this plan was not followed, for the defences along the Struma were much less formidable than around Doiran, or in the Moglena Mountains. It is possible that the new Commander-in-Chief, always inclined to take snap decisions on first impressions, failed to appreciate the value of the Struma route after he visited the Greek Corps there, in company with Milne, on 19 July. It was a fifty-mile journey from Salonika, the temperature reached 1 o F in the Struma valley, and in contrast to his experience with the Serbs, Franchet was not impressed by the Greek contingent. (Nor indeed was Milne when he paid a surprise visit to the Greeks three weeks later and found that, though outposts were fully manned, their occupants saw no reason to forgo an afternoon siesta).

If he was to order an assault on the heavily fortified Bulgarian positions above Doiran, Milne needed howitzers and several shipments of shells. He began at once to press a reluctant War Office for these supplies. But, in dealing with London, Milne made a tactical error. His messages back to the CIGS showed, as his biographer remarks, not so much a ‘cautious optimism’ as a ‘tempered pessimism’. They also perpetuated the suspicion that French strategy was linked with political and commercial ambitions in the post-war world, practices which stood out so flagrantly during the Sarrail era. Yet was it sensible for Milne to expect a steady supply of arms and ammunition for an offensive which he thought was being fought for French national interests and in the outcome of which he expressed so little confidence? Urgent telegrams to London seeking ammunition and shells were sent on four occasions. They remained unanswered. Eventually, twenty-four hours before his artillery was due to open up on the Doiran positions, Milne received his first shipment of shells, only one-fifth of the number he had requested. As other reinforcements, there arrived some Indian drivers for the ammunition train, and a small consignment of Lewis guns. Haig’s needs in France had priority.

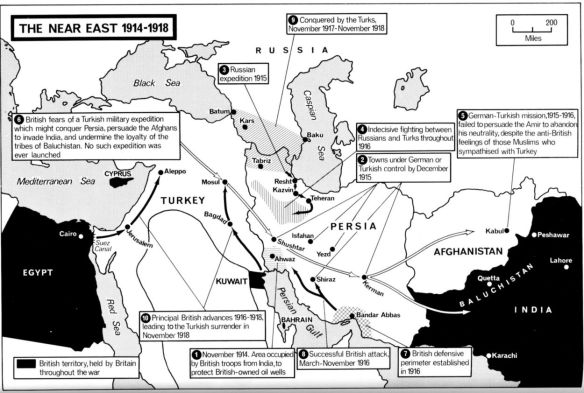

To troops manning the defences in Macedonia and other outlying theatres during the first days of August 1918, it would have seemed improbable for the war to end victoriously within three and a half months. The German Empire was still the predominant power in Europe, from the Belgian coast to the Urals. Although Germany was shaken by strikes and violence in January 1918 the peace treaties of Brest-Litovsk and Bucharest (with Romania) gave promise of food, oil and material goods from the East, lifting morale throughout the summer despite the failure of the Western offensives. Expansionist groups in Berlin and Army headquarters at Spa in Belgium continued to develop plans for exploiting their gains from the old Russian Empire. Ludendorff, echoing the views of the nationalist Fatherland Party, sought the creation of puppet states from the Dniester to the southern Caucasus, with the Crimea a German dependency, offering Junker land-owners a Prussian riviera and the Imperial Navy a base from which to dominate the Black Sea. To promote these dreams Ludendorff was prepared to leave forty divisions — one and a half million experienced troops — in the Ukraine and southern Russia while the armies in the West were seeking to break through to the Channel ports or Paris. When, on 23 May, Georgia proclaimed independence and asked Germany for military and political protection, Ludendorff advised immediate acquiescence and recommended to the Foreign Ministry in Berlin that similar appeals from other peoples of the Caucasus should be treated sympathetically. If German ambitions in the East clashed with Enver’s dreams of a pan-Turanian empire, the Turks must come to heel; a peremptory order from OHL on 8 June insisted, on grounds of joint general strategy, that the Ottoman armies should seek to advance, not farther into the Caucasus, but southwards into Mesopotamia. Possession of the Baku oilfields was vital for Germany, Ludendorff insisted in July. As late as 9 August a conference of senior representatives of the Army, Navy, Foreign Ministry and the Trade and Industry Ministry emphasized the need for German economic control of the Caucasus and a ‘sphere of influence’ to include ‘the Mesopotamian oil-wells’.

The British had been aware of the German threat in central Asia even before the Brest-Litovsk Peace Treaties were signed. In the War Cabinet both Milner and Curzon stressed the important role of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force which, since the death of General Maude in November 1917, was commanded by General Sir William Marshall. Despite having to send the 3rd Indian Division to Egypt for service under Allenby, Marshall sought to satisfy the often confused instructions reaching him in Baghdad from London. The Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force pursued the Turks up the Euphrates to the ancient town of Hit in March 1918 and pressed further northwards on the long road towards Aleppo, making effective use of light armoured cars. It was a tedious terrain; ‘Miles and miles and miles of damned all’ was one veteran’s succinct comment in his diary. At Khan Baghdadi, on 27 March, a cavalry brigade cut off the Turkish defenders, taking 5,000 prisoners; armoured cars pursued the rest of the garrison up the Aleppo road and captured the Turkish commander and the chief of the German Intelligence mission. But by April both the War Office and the India Office were so alarmed at the activities of German agents along what the Kaiser had called ‘the bridge to India’ that the CIGS ordered Marshall to shift the main emphasis of his advance away from the Euphrates and across to the Tigris and Kurdistan. He was to stop any German or Turkish attempt to control northern Persia.

Marshall knew, from experience, the limitations imposed by geography and climate in such a distant theatre of war. He was being asked to penetrate much hillier country, where the temperature was more equable than in the plains around Hit but where heavy storms could soon turn gullies into wide torrents. To an even greater extent than Allenby in Palestine, his operational timetable was dictated by rainy seasons and hot weather. Moreover, there was a danger that — like Townshend in 1915 — he might advance so rapidly as to place an impossible burden on supply routes. Marshall’s 13th Division — a cavalry brigade with horses and armoured cars, and mobile columns of infantry from Lancashire and Staffordshire in several hundred Ford trucks — set out north-eastwards after nightfall on 26 April, the way ahead illuminated for them by flashes from an electrical storm. They covered 150 miles, to take Kirkup on 7 May; but the strain on Marshall’s supply line proved so severe that, two and a half weeks later, he decided to evacuate the city, falling back with his troops protecting some 1,600 Kurdish refugees, fearful of Turkish reprisals. Like Allenby, he would wait until the passing of the hot weather before resuming an offensive against troops who, as on so many other fronts, were showing less and less inclination for sustained resistance.

But this was not what London wanted. The War Office might, in this critical summer in France, treat Salonika and Palestine as sideshow irrelevancies, but the German thirst for Middle East oil ensured that on several days Mesopotamia held centre stage. A telegram from the CIGS on 28 June complained that Marshall ‘was not taking full advantage of our opportunities… a greater and more sustained effort must be made in north-west Persia… Your main attention must be directed against Persia and the Caspian’. Calmly Marshall remained on the defensive. Little action was possible in the summer heat, when the shade temperature in the encampment north of Baghdad had climbed to 125° Fahrenheit. He did, however, shift the spearhead of his forces to cover the northern frontier of Persia; it was cooler in the high plateau. And, in the strangest of many twists on the road to victory, Marshall hastily improvised ‘Dunsterforce’.

There had never been any possibility that Marshall could send a fully equipped army into Persia, across mountains as forbidding as the chain along the Greek-Serbian frontier, so as to secure the Baku oilfields; they were as far from Baghdad as Warsaw from Haig’s headquarters in France. In the last week of January 1918, however, a military mission of forty-one Ford trucks and armoured cars set out from Baghdad to establish a British presence in the Caucasus. At their head was Major-General Dunsterville of the Indian Army, who forty years previously had shared a school study with Rudyard Kipling and was the original model for the fictional Stalky. Most of Dunsterville’s military career had been along the north-west frontier of India; he was a qualified interpreter in Russian, Chinese, Persian, Urdu and Punjabi and also spoke German and French. His convoy crossed into Persia and covered 345 miles in fourteen days, through the almost snow-blocked Asadabad Pass, to rest at Hamadan on 11 February before following a good, Russian-built road for 150 miles and reaching the more important town of Qazvin on 16 February. Dunsterville was still 150 miles from Persia’s Caspian seaport of Enzeli (also known as Bandar-e Pahlevi), and Baku itself was another 200 miles north across the sea. The General was now delayed, partly by hostile action by Persian tribesmen and partly by the complications of shifting loyalties in Russia’s protracted civil war. By midsummer — with a mainly Turkish army concentrating in Tabriz, ready to march through Azerbaijan to Baku — the urgency of Dunsterville’s needs prompted Marshall to find the men and lorries for the specially designated Dunsterforce’. Hence on 1 July — while US Infantry were storming the village of Vaux, outside Château-Thierry, and Britain’s Prime Minister was ‘motoring’ from Dieppe to Versailles to confront Clemenceau over the Salonika Question — four battalions of British infantry left the 39th Brigade camp north of Baghdad for the Caspian Sea, where Dunsterville was already supported by a battalion of the Hampshire Regiment, a squadron of Hussars, some armoured cars and several thousand anti-Bolshevik Cossacks.

The 39th Brigade took five weeks to reach Dunsterville at Enzeli, the first three companies of the North Staffordshire Regiment arriving on Sunday 4 August. While the lorries had carried them for 500 miles, they had covered nearly 150 miles on foot, escorting pack camels through deep forests and two mountain passes. Other troops completed the long trek during the week, though sickness reduced their numbers. By Wednesday they were in Baku, having sailed aboard a commandeered steamer named in honour of President Kruger. For over a month — decisive weeks for the war in Europe — infantry from Warwickshire, Worcestershire, Hampshire and Staffordshire, supported by a battery of field artillery, armoured cars, two Australian planes, partially trained Armenians and Russians of varying loyalty resisted a Turkish force of more than 12,000 men. Dunsterville did not attempt to destroy the oilfields (though some were damaged by shellfire) because that would have provoked desperate resistance from the local Tatar oil-workers. On the night of 14 September three steamers evacuated Dunsterforce, and many civilian refugees with it.

Next morning the Turks entered Baku and set up an administration headed by Enver’s brother, Nuri. Technically the Dunsterforce ‘sideshow of a sideshow’ had proved a failure; and, in the mounting drama of the following weeks, its remarkable achievements went largely unnoticed at home. But the long resistance paid a negative dividend. For, by the time the war ended, not a single barrel of oil from Baku had reached the German or Ottoman armies in Europe or Syria. The ambitions of Ludendorff and Enver remained pipeline dreams. On 17 November the SS President Kruger brought British troops back to the Baku quayside.