News of Ludendorff’s third thrust, the drive from the Chemin des Dames to the Marne, was brought to Lloyd George on 27 May 1918 by the CIGS seven hours after it began. Hankey was present and describes how, on hearing the bad news from the Front, the three men began to look ahead, sombrely assessing the war situation. Two months of ‘great anxiety’, Sir Henry Wilson predicted, would be followed by two months of ‘diminishing anxiety’. If the Allies survived those four months, they ought — by October 1918 — to be at the start of ‘a long interval’ during which they could prepare for one massive co-ordinated stroke to overcome the Germans in the following year; the interval might also be used for ‘striking some blows in the outlying theatres’. It was a gloomy prospect, postponing fulfilment of even the limited expectations outlined in January’s Joint Note 12. The outlook did not improve over the following fortnight. Secret discussions on 30 May and 5 June considered what was to be done if the Channel ports had to be abandoned, or if it proved necessary to withdraw from the Continent entirely, should ‘the French crack’. The spectre that was to become a reality in 1940 seems almost to have cast a forward shadow as this earlier war reached its climax.

Concern in London and Paris over perils close at hand left the managements in ‘outlying theatres’ free to mount programmes of their own devising. Allenby, frustrated by the forced abandonment of his spring offensive at Whitehall’s demand, sought in early May to establish and retain a commanding position at Es Salt, threatening Amman over the Jordan valley. This second Transjordan raid, which was made by Australians and New Zealanders, with three brigades of the London Division, failed for three reasons: promised local Arab support was not forthcoming; air reconnaissance failed to spot a large Turkish force, concealed in broken scrub; and the relatively few tracks in hilly terrain could easily be covered by defensive fire. The Australians and New Zealanders, supported by two battalions from the West Indies and by the Jodhpore Lancers, remained in the almost unbearable heat and humidity of the Jordan valley throughout the summer, successfully fending off a German-led counter-attack in July. Meanwhile, at his Bir Salem headquarters in the coastal plain, Allenby studied the lessons of the Transjordan raids. His victory at Gaza had been won by an unexpected thrust inland. Should he follow this strategy in a modified form a year later? The raids showed that progress through the hill country would be painfully slow and costly; ought he to revert to the traditional route up the coast? And how far could he rely on Arab support? The flame of Arab nationalism, which glowed brightly after the capture of Aqaba, could not fire the spirit of sheikhs of the Jordan valley.

Despite the disappointments of the spring Allenby did not intend to remain on the defensive. From Turkish prisoners captured by patrols, and from a steady stream of deserters, he realized that the troops facing him in northern Palestine felt far less committed to fight than the defenders of Gaza and Jerusalem in the previous autumn. Even though his armies were seriously depleted, he began to look ahead confidently to the peak campaigning season, those eight or nine weeks between the passing of high summer and the coming of the early November rains.

There was now little risk of a German-Turkish attempt to recover Jerusalem, although rather curiously Allenby mentioned such a possibility in conversation with the Zionist leader, Chaim Weizmann. The Yildirim grand design, which looked so menacing on paper, had proved as insubstantial as a mirage, as Falkenhayn realized once he sought to lead the Turks in the field. After five months in Asia Falkenhayn welcomed a recall to Germany in the last days of February 1918; his war was to end obscurely in Lithuania, protecting German garrisons from the wrath of the Poles and the enticements of the Bolsheviks. But Falkenhayn’s departure did not make the task of the EEF any easier, for he was succeeded by Liman von Sanders, head of the military mission to Turkey before the war and commander in defence of Gallipoli. Liman might not possess so brilliant a military mind as Falkenhayn, but he understood the Turks, had built up their army on the eve of war, and was respected by them. Behind Liman in Constantinople, as Chief of the Ottoman General Staff, was General Hans von Seeckt, perhaps the most skilful German staff officer of the twentieth century. Yet neither Liman nor Seeckt could lift the fighting spirit of troops who had served in the front line too long without relief and lived on subsistence rations, receiving no more than 350 grams of bread a day. Liman himself reckoned that, between the start of the war and Falkenhayn’s recall, as many as 300,000 Ottoman soldiers had deserted, a figure half as large again as the number of troops currently serving in the field. Despite the leavening of good German and Austro-Hungarian specialist troops still serving in Syria, there was every reason for Allenby to strike hard against the hungry and demoralized Turks as soon as he could replace the divisions sent to France.

Manpower, however, remained his most pressing concern. Increasing use was made of units which might foment discontent among peoples subject to Turkish domination: three specifically Jewish ‘Judaean’ battalions, mostly recruited from the bigger English towns, were formed within the Royal Fusiliers as a nucleus for the Jewish Legion long envisaged by Lloyd George. The French similarly raised three Armenian battalions, including refugees rescued by French warships in 1915; they formed the nucleus of a Legion d’Orient which was intended to win the backing of Armenians in Syria for the French. The 3rd Indian Division arrived from Mesopotamia in April and more reinforcements from India between June and August, replacing Australian and British troops sent to France, but Allenby was uncertain of their effectiveness. As a young man he had sought entry to the Indian Civil Service, but failed the examination; he never visited India and knew little of the Indian Army or its traditions. He saw for himself at Messines in 1914 the appalling casualties suffered by the 57th Indian Rifles, as they encountered trench warfare for the first time; and he was strongly opposed to employing Indian artillerymen in Palestine, apparently from fear of mutiny or sedition. He was worried by problems of religious obligation; almost a third of his Indians were Muslim, and German Intelligence ensured that pan-Islamic appeals printed in Urdu were circulated among the troops arriving in Egypt.

So concerned was Allenby over the risk of Muslim fighting Muslim that on 2 June he even suggested in a telegram to the War Office that three or four Japanese divisions might be brought to Suez, for service in Palestine and Syria; the Japanese were the one ally with a good army unlikely to be swayed by religious sentiment in the Holy Places. Already fourteen Japanese destroyers and a cruiser were in the Mediterranean, regularly escorting convoys between Malta, Alexandria and Port Said. But Japanese military pride made it unlikely that Emperor Yoshihito would have let his troops play the role cast for the Portuguese in France. Moreover, the British were at that time encouraging the Japanese to join the Americans in occupying Vladivostok so as to prevent stores accumulated at the head of the Trans-Siberian railway from being moved westwards for the Bolsheviks to barter with the Germans and their allies. The War Office turned down Allenby’s request, apparently without reference to Tokyo.

He also learnt from Whitehall in June that there was little prospect he could receive any troops from France or Italy before the end of the year. Throughout that critical month in the West, he was even uncertain if he would be able to retain three Australian light cavalry brigades and the 54th East Anglian Division. Not until 26 June did the War Cabinet discuss Palestine, and decide that there was now no longer a need to withdraw further forces from his command. The retention of these troops — particularly the Australian horsemen — were essential to the plans Allenby was perfecting during the hot weather. His armies still enjoyed a two-to-one superiority in infantry, cavalry and firepower over their Ottoman and German enemies; and six squadrons of the Royal Air Force, together with an Australian squadron, ensured mastery of the skies. The terrain and the climate imposed more formidable problems on Allenby’s planners than likely enemy resistance. And there were political vexations, too: a well founded suspicion that Feisal might be responding to almost secret approaches from the Turks; and constant doubts over the next move of that indefatigable intriguer, the French ‘High Commissioner for Palestine and Syria’, Francois Georges-Picot.

Such problems Allenby was content to leave to the Arab Bureau in Cairo and to the experienced Storrs, now his Military Governor in Jerusalem, but their mounting complexity emphasized the need for a decisive victory as speedily as possible. When, on 15 June, Allenby made it clear at GHQ that he wished to resume the offensive, his intention was to advance only as far north as the administrative boundary between Syria and Palestine. Such a plan corresponded to the cautious encouragement he received from London, when Whitehall remembered his existence. But soon the lure of Damascus began once more to appeal to him. By the beginning of July his thoughts were outpacing his planners. A month later his mind was made up. One morning in the first week of August he returned to headquarters from a ride, ‘strode into his office’ and told his operations staff that his objective was more ambitious: Ottoman power in Syria must be destroyed before the rains came. ‘Time is the enemy, rather than the Turks’, he was to tell his staff officers more than once during the following weeks.

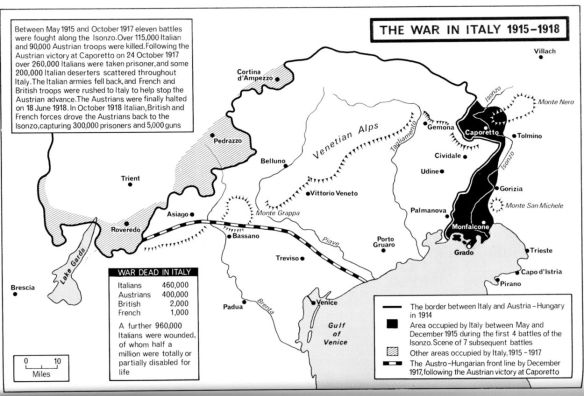

The War Cabinet’s change of heart on 26 June was a direct consequence of good news from Italy, giving hope that General Diaz’s armies would soon be able to penetrate central Europe without help from his three British divisions, which could then return to France. On 15 June what was to become the last Austro-Hungarian offensive had been launched, with the customary bombardment of high explosive and gas shells; within six days it could be clearly written off as a failure.

The June offensive was the brainchild of the veteran Conrad and the Croatian-born Field Marshal Svetozar Boroevie von Bojna and was more ambitious than Caporetto. Unlike the series of assaults directed by Ludendorff in France, this attack extended along the whole of the Italian Front, from the Tonale Pass, close to the Swiss border with the Tyrol, through the British and French held Asiago plateau and down the Piave to the Adriatic. Conrad would make the main thrust, striking southwards from his headquarters at Trent and breaking through the mountains to Vicenza. Boroevie would cross the Piave, take Treviso, isolate Venice and advance on Padua. If by then the Italians had not sued for peace, he would press forward to the Adige and meet Conrad in Verona. It was a reversion to sound, old-fashioned war games strategy, a ‘brush-up-your-pincer-movement’ exercise. Perhaps in 1914 or 1915 the old Habsburg Army might have pulled it off; but not a tired and hungry army, with some infantrymen going into battle in boots with paper soles.

Throughout the early months of 1918 large sections of the multi-national army were on the verge of mutiny, as Conrad and Boroevie knew well. While they were planning the offensive no less than seven army divisions were stationed far from the war zones, for purposes of internal security. On 1 February a mutiny, begun by Czech agitators aboard the Szent Georg, flagship of the Austro-Hungarian cruiser squadron at Cattaro in southern Dalmatia, spread through forty warships before it was suppressed. Red flags were flown, but the mutineers’ programme called merely for better food, an end to the war and genuine national autonomy; an enterprising junior officer and two petty officers escaped punishment by seizing a seaplane and crossing to Italy. Army mutinies came with the spring. During May, troops ordered to the Front refused to board their trains: there were mutinies of Slovenes in western Syria, Ruthenes in Ljubljana and Czechs at Rumburk, a small garrison town close to the frontier with German Saxony. Returned prisoners of war from Russia had no wish for further battle experience. ‘Reliable’ guard regiments herded the mutineers into sealed railway waggons for the journey to the Front. The contrast with the meticulous preparations for the Fourteenth Army’s attack in the previous October was striking. It is curious that Emperor Charles showed any confidence in Conrad’s planning. He was slow to realize how far the privations of the past seven months had blunted old loyalties.

In the Italian war zone itself there was a constant stream of deserters from the Kaiserlich-und-Koniglich joint Army, particularly in the Trentino. Further south the rivers were a hindrance; a Polish gunner, captured later in the summer, told the Italians that many of his compatriots had wished to desert, ‘but were put off by having to swim across the Piave to give themselves up’. Slovaks and Romanians from Transylvania, conscripted into the Hungarian Honved regiments, complained of brutal treatment by Hungarian NCOS and officers. ‘The Austro-Hungarian soldier receives more blows than bread’, one Slovak deserter told his Italian interrogators. For four days in the second week of April a ‘Congress of Oppressed Peoples’ met in Rome, attended by spokesmen for the Italian, Czecho-Slovak, southern Slav, Polish and Romanian minorities within Austria-Hungary and affirmed a determination to carry on a common war of liberation from Habsburg rule so as to secure the establishment of ‘completely independent national states’ in post-war central Europe. The Congress was given great publicity by the Italian press and the British propaganda machine. But shortage of food was a greater incentive to desertion than political manifestos. Most foot soldiers were sent into battle after subsisting for weeks on a daily ration of eight ounces of black bread, three ounces of meat and, occasionally, some thin vegetable soup. Rumour encouraged a belief that behind the Allied Front there were good stocks of food, drink and tobacco, an illusion sustained by leaflets dropped from Italian planes. During the six-day battle 12,000 Austro-Hungarian troops took the opportunity of coming over to enemy lines, painfully conscious that they had, almost literally, no stomach for the fight.

The Comando Supremo had long anticipated the June offensive and General Diaz had prepared good defences in depth, especially in the north. Some of the heaviest fighting on 15 June was on the Asiago plateau, where the two French divisions held to their line, while the British recovered within a day a small segment lost under the weight of the first attack. Only on the lower Piave was there any echo of the Caporetto panic among the Italian infantry. There Boroevie’s troops established bridgeheads along a fifteen-mile front. But the river crossings were immediately bombed with great accuracy by a Royal Air Force squadron; and the swift-flowing river, its water level raised by heavy rain on 16-17 June, swept the pontoon bridges away. Morale among the sapper bridge-building units within the K-und-K Army evidently remained high, for engineers made a courageous attempt to save one important bridge from disintegrating in the swirling waters. But, in general, there was little will to fight a protracted battle. By the end of the week, when Diaz felt able to order cautious counter-attacks, the Austro-Hungarian army had lost over 80,000 men as battle casualties or through desertion. When, on 16 June, the Emperor Charles was informed of the failure to break through the Allied defences, he became finally convinced that the war was lost. Over the following months he was to authorize drastic experiments to preserve the integrity of Austria-Hungary, but he could offer little to counter the persuasive appeals of Masaryk, Beneš, Trumbie and the Polish spokesmen abroad. On 28 June — the fourth anniversary of the assassination at Sarajevo — France took the lead in giving official political recognition to a breakaway movement: the Czech-Slovak National Council in Paris, led by Dr Beneš , was accepted as ‘supreme organ of the nation and the first basis of a future Czecho-Slovak government’. British recognition followed on 9 August; American on 2 September.

The defeat of Austria’s summer offensive convinced the military leaders in London and Paris that Italy need no longer be treated as the Entente’s poor relation. The willingness of the Comando Supremo to send brigades to France and to help protect the stores accumulated at Archangel in northern Russia seemed to confirm their hopes that the Italian theatre could be left once more to King Victor Emmanuel’s officers and men. But Diaz secured the retention of the five British and French divisions as a visible guarantee of Allied good faith should his troops become war-weary when autumn returned. Diaz was also eager for an American presence in Italy, an issue over which he was strongly supported by the Prime Minister, Orlando; every politician from southern Italy knew from personal experience of the warm and deep emotional ties binding Italian peasant families with kinsfolk across the Atlantic. Pershing was unsympathetic but was overruled from Washington. On 25 July the 332nd Infantry Regiment, part of the American 83rd Division newly landed in France, was transferred to Italy; and their arrival was rapturously welcomed by the press. ‘They come with rifles and high hearts to defend the freedom of the world wherever it may be threatened’, the Tribuna declared on 29 July; and in his Popolo &Italia next day, Mussolini — a warm supporter of April’s Congress of Oppressed Peoples — wrote that only from America might new men and new ideas be expected to come; he still professed admiration for President Wilson. It was a period of grand, symbolic gestures. Eleven days later — 9 August — the fifty-five-year-old dramatist and poet Gabriele d’Annunzio flew as pamphlet-aimer passenger in an SVA-5 reconnaissance aircraft escorted by seven fighters, on a 625-mile round trip to drop leaflets over the Austrian capital. The Viennese were praised for their intelligence, told to think dispassionately of the future, and urged to shake off ‘Prussian’ fetters while they had the opportunity. Had their message been printed clearly in German rather than in the Italian language superimposed on an Italian national flag, the leaflets might have aroused more interest.

D’Annunzio’s propaganda mission was acclaimed by the Italian press. But, predictably, the leaflets did not cause any rattling of fetters. In reality, since May, when angry verbal exchanges between Czernin and Clemenceau alerted to the extent of Charles’s peace overtures the previous year, the Germans had tightened their grip on Austria-Hungary; a Waffenbund, ‘armed forces alliance’, bound the two armies closely together. Despite the losses in Italy, the Germans insisted that summer on a strengthening of the K-und-K contingent on the Western Front. Although some Hungarian punishment troops sent to the Argonne crossed the lines at the first opportunity, there were still 18,000 officers and men serving in France during the autumn as Austria-Hungary faced disintegration.