Turkey’s entry into the war on the side of Germany had far-reaching implications for the Allies in other places than the Dardanelles. Ultimately, it also led to campaigns in Egypt and Palestine, Macedonia and Mesopotamia (present day Iraq). Mesopotamia, part of the Ottoman Empire, was crucial to the Allied effort as a major supplier of oil to Britain, mostly through the Anglo-Persian Oil Company at Abadan Island in the Shatt-al-Arab. In 1914, when relations with Turkey were deteriorating and the Germans were spreading anti-British propaganda in Mesopotamia, the British government moved quickly and secretly set up a force in the Persian Gulf. However, it was made up of old vessels that might have been capable of dealing with any Turkish vessels in the vicinity but would have been easily overcome by the German cruisers Emden and Konigsberg when they were at large in the Indian Ocean. Therefore Ocean, another older vessel but a battleship, commanded by Captain Hayes-Sadler, was also sent out to the Gulf. Indian troops were sent to Bahrain, where the Sheik was sympathetic to British operations, and initially the Indian Government, with Royal Navy support, was responsible for operations in the Gulf. The troops, under the command of Brigadier Delamain, reached Bahrain on 23 October 1914 but, when the Turkish navy attacked the Russians in the Black Sea, they were ordered to the Shatt-al-Arab, and another brigade, Force D, was sent to the Gulf. The Indian troops silenced the guns at the Fao at the entrance to Shatt aI-Arab, where a small garrison was left, while Delamain’s 10th Brigade set up camp about two and a half miles away from the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s refinery. The Navy light-armed sloop Espieqle was stationed to protect the refinery.

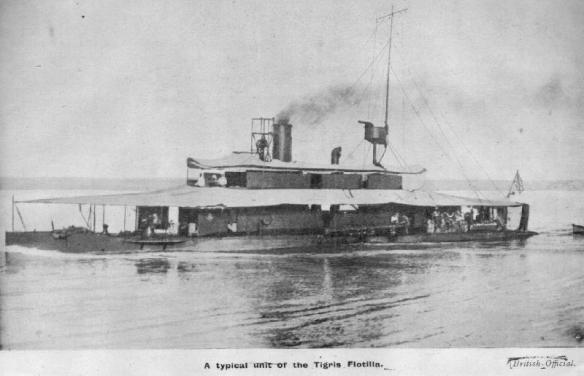

The main objective was to protect the oil pipeline and capturing the port of Basra was seen as essential, since it was the main outlet for the area. It was essentially an Army campaign but the Navy had an important role in that the action was along the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. The main aim was achieved when reinforcements under Lieutenant General Sir AA Bartlett arrived to join Delamain’s troops. They advanced on 19 November and, by 22 November, the troops, along with the Royal Navy ships Espieqle, Odin and the paddle steamer Lawrence, had taken the port. The British agent in Basra, Sir Percy Cox, was keen that they should capitalise on the victory and push on further to Baghdad but the Government of India, considering the limited number of troops and the difficulties in communications, felt that it was too soon. A compromise was reached whereby it was agreed that the troops would advance as far as Kurnah which, being a point where the rivers Euphrates and Tigris joined, was a strategically sound location to guard the whole of the Shatt-al-Arab. Again the Espieple and Odin were alongside, although the Odin damaged her rudder in the shallow waters and much of the support work was undertaken by paddle steamers and river gunboats. On 9 December Kurnah was taken and the Turkish commandant captured.

In March 1915, the Navy was also involved in attempting to cut off Turkish supplies carried down the Euphrates. A flotilla was put together including two armed river steamers, a barge with a 4-inch gun, tugs and motor- boats and, in the main, they were successful in pursuing dhows that carried the supplies through the uncharted river. However, the Turks were building up their troops in Mesopotamia and the British realised that they would need to strengthen their own position. Another Indian brigade was diverted to the area and the sloop Ciio was sent in a bid to maintain control of the area. The priority was still to protect the oilfields and pipelines but the British also wanted to capture Baghdad. The British and Indian troops succeeded in counteracting the threat to Basra from the reinforced Turkish force.

Following on from this success, the aim was to take Amara where there was a possibility of intercepting retreating Turkish troops. By collecting numerous bellums- native wooden canoes – the operation was turned into an amphibious one. It was an unusual campaign for the Royal Navy as the flotilla took the place of cavalry. Along with the bellums were the three sloops as well as two launches fitted with sweeps, two gun barges, two armed horse boats and a large flotilla of smaller vessels. Starting on 31 May, the troops achieved great success, securing Amara within four days. There was growing confidence and, indeed, operations in Mesopotamia had been some of the most successful of the war. This led to the decision to push for a capture of Baghdad, which, if achieved, would effectively cut German communications with Persia and Afghanistan. There was a delay in waiting for permission to go ahead from London and also because the river was at low water. The Navy sent out HMS Firefly, the first of the new Fly- class vessels, which were gunboats, ordered by Fisher that had been originally intended for working in the Danube. However, the flotilla was unable to be of much assistance to the soldiers as they tried to break through the Turkish troops in November because the banks were too high and the gunboats were vulnerable to artillery attack. The army under Major General Townshend was forced to retreat and the flotilla, in assisting the troops, lost a launch that ran aground. Then, on 1 December, Firefly was Significantly damaged by artillery fire. The tug that tried to save her ran aground and both had to be abandoned. By 9 December, Townshend and his army were besieged at the town of Kut. Between January and April of the following year, there were continual but unsuccessful attempts to relieve them.

More Fly-class vessels were deployed along with Mantis, a large gunboat, but really much more powerful resources were required if they were to have any effect. The river steamer juinar made a desperate effort to get supplies into Kut but she came under Turkish fire and ran aground. Her commander was killed by a shell and her second-in- command was murdered by the Turks after capture. It had been hoped that success at Baghdad would recover some of the prestige lost in the Dardanelles but, on 29 April 1916, Townshend was forced to surrender.

In February 1916, during the siege, the War Office took over control of the Mesopotamian campaign from the Government of India. In August 1916, Lieutenant General Sir Stanley Maude was made commander-in-chief of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force with instructions to maintain British control of Basra and the surrounding area. and, in February 1917, he finally re-took Kut. It was decided to renew efforts to take Baghdad. In the mean- time, the flotilla had been guarding lines of communication against raids and had been reinforced with the additional gunboats, Tarantula and Moth. They took part in the advance, again acting as cavalry, and suffered heavy fire and many casualties but they battled through. In their retreat the Turks left behind the previously abandoned Firefly and she was taken back into the flotilla along with a Turkish steamer and a tug. The gunboats caused great panic amongst the Turkish army, sending many into flight. At last, on 11March, Baghdad was occupied by the British and they took control of the Mosul oilfields.