Within three years the royal marriage of King Fulk and Queen Melisende was in serious trouble and the kingdom of Jerusalem on the verge of its gravest political crisis to date. Two of the most influential men in the land, Count Hugh of Jaffa and Roman of Le Puy, lord of Transjordan, conspired to challenge King Fulk. Their motivation was a combination of the personal and the political, and represented the entwined interests of Queen Melisende and the native nobility.

Hugh was in the prime of life: about twenty-eight years old, he was tall, handsome, and a distinguished warrior. William of Tyre eulogized: “In him the gifts of nature seemed to have met in lavish abundance; without question, in respect to physical beauty and nobility of birth, as well as experience in the art of war, he had no equal in the kingdom.” The count was the son of Hugh II of Le Puiset who had set out on crusade in 1106–7. En route to the Levant his wife had given birth to a son in Apulia. The boy had remained at the Sicilian court until he came of age when he traveled to the Holy Land and sought his inheritance from King Baldwin II around 1120. He was related to the royal house of Jerusalem through his father, and his family ties and career made him a natural associate of Melisende. Soon after 1123 he married Emma of Jaffa, the widow of Eustace Grenier (in his day the most powerful landowner in the kingdom and a royal constable). Emma must have been rather older than Hugh because she already had two sons, Eustace, lord of Sidon, and Walter, lord of Caesarea, both of whom were adults and important nobles in their own right.

During the early 1130s tensions began to simmer between the king and Count Hugh. The count grew arrogant: he refused to obey royal commands and started to drift toward open defiance of his monarch. Hugh was an immensely influential noble in his own right and the county of Jaffa was probably the wealthiest lordship in the kingdom of Jerusalem. Charters indicate that he enjoyed the full trappings of a royal household, including a chancellor and treasurer. His position was unique in the kingdom: no one else possessed the title of count; in fact, the only other men in the entire Levant with such a rank were the count of Tripoli and the count of Edessa.

As the friction between the two men became increasingly overt Hugh began to formulate a strategy. Almost nine centuries later, the details of his conspiracy are elusive, but we are fortunate to have a charter from the principality of Antioch that yields dramatic evidence. A document dated July 1134 places Hugh in the court of Melisende’s sister, Alice of Antioch. The princess had already shown herself to be the most independently minded and rebellious individual in the Latin East by staging two uprisings against the king of Jerusalem. This being so, it is unlikely to have been a coincidence that the count traveled over 280 miles north to see her. He must have gone to sound her out and alert her to the likelihood of open confrontation. As the champion of Melisende’s cause it is logical that he would want to enlist the help of the queen’s sister.

As the political momentum behind Hugh and Melisende increased, another, more personal, aspect to the situation became apparent. Fulk began to suspect the count of being more than simply friendly toward the queen. Perhaps he felt insecure—he was an older, placid man who may have been threatened by the obvious familiarity between Melisende and her dashing contemporary. Some whispered—tantalizingly—that there was proof of a more intimate relationship, yet none of our sources offers details. In such circumstances it is hard to make a genuine assessment of the truth. Sexual innuendo was, and remains, one of the oldest and easiest ways to disparage an opponent’s name, and if the gossip came from the royal camp it could have had a far wider impact. Such rumors obviously impugned the good name of the queen herself and if an open allegation of adultery were proven the legal process would be barbaric. The queen could undergo an ordeal by fire and if found guilty, according to laws laid down in the 1120 Concordat of Nablus, she would be punished by rhinotomy, the slitting or cutting off of her nose; Hugh would be castrated. Melisende might then share the fate of the lady of Banyas, a woman found guilty of adultery, although in this instance at the hands of her Muslim captors, and be sent to a convent. No medieval queen had been treated in such a way, but in the poisonous atmosphere of 1134 such an outcome was a theoretical possibility.

Unsurprisingly, when the matter of his wife’s infidelity was coupled with the simmering political conflict, Fulk conceived “an inexorable hatred” of Count Hugh. Charges of adultery reflected badly on the vitality of a king who seemed unable to preserve the sanctity of his marriage bed. Such an accusation would also damage the standing of the infant Baldwin, although, as we have seen, Elias, Fulk’s grown son from his first marriage, was waiting in the wings. It would be too sensitive to air the accusations of adultery in a formal setting—if Fulk was to flush out the conspirators, then the political route offered the best way forward.

At the suggestion of the king, and perhaps out of loyalty to his mother, Countess Emma of Jaffa, Walter of Caesarea brought the matter to a head. At an assembly of the royal court of Jerusalem Walter made the most sensational and inflammatory claim possible: that Hugh and certain companions had conspired to kill King Fulk. The fact that Walter confronted his own stepfather added an extra sharpness to the situation. Regicide was extraordinarily rare: the sanctity of kingship meant that except in open battle—such as King Harold at Hastings in 1066—slaughtering God’s anointed representative was almost unheard of. The fact that the king’s own wife and her alleged lover were behind such a move made this story even more incredible.

This was a moment of the highest tension: the king and the count faced each other across the royal court. The older man was trying to grasp the power he believed to be rightfully his, the other sought to preserve the status and dignity of the queen of Jerusalem. At the heart of this conflict was Melisende, the pivot around which the entire struggle turned. When he heard the accusation Hugh stood firm; he stated that he was innocent of this heinous charge. Proof may be difficult to provide, however. In the belief that he had allies among the native population the count turned to the court of his peers and said that he would submit to their judgment. The barons and leading churchmen of the land conferred. Could they condemn one of the most important nobles in Outremer, or should they join him, and break with tradition to defy the anointed king? In the early twelfth century an accuser and witnesses spoke to the court and then the nobility debated the outcome. The idea of a prosecution, a defense, and trial by jury were not invented in a form recognizable to us until the reign of King Henry II of England, forty years later. In the medieval mind-set only God could know the truth. The court decreed the matter should be settled by single combat, as was the fashion in contemporary France and Germany, and a date for the trial was set. Hugh and Walter were to face each other, fully armed and mounted on horseback. They would charge at each other until one was unhorsed. The rider might be able to finish off his opponent at that point, or he could dismount and begin hand-to-hand fighting. Sometimes the struggle was so close that the men ended up wrestling unarmed. In one contest the winner secured victory by biting off his enemy’s nose, in another by wrenching his opponent’s testicles. The defeated man was usually slain.

Hugh returned to his lands at Jaffa, but on the day designated for the ordeal he failed to attend. Some interpreted this as an admission of guilt and there was disquiet even among his own supporters. Walter was famous for his strength and perhaps Hugh feared his stepson’s fighting skills. In any case, the High Court condemned Hugh’s absence and he was found guilty of treason and his lands forfeit. Had he fought and won, Fulk’s position would have become untenable.

William of Tyre described Hugh’s reaction to this news as a combination of panic and foolishness: on hearing the court’s verdict Hugh sailed south forty miles from Jaffa to Muslim-held Ascalon. He asked the inhabitants for help against the king—something they readily agreed to. As we have seen, treaties between Christians and Muslims were a fact of life in the Levant; the difference here was the state of division among the Christians, which made Hugh’s presence of particular interest to the Ascalonites. The count argued that he had support within the kingdom and that he could offer—presumably relying on Melisende’s agreement—something to the Muslims in return. We know that they already paid King Baldwin II an annual financial tribute, so a reduction, or even a termination, were the most likely bargaining chips available. An agreement was sealed with an exchange of hostages, again a common custom, and Hugh returned to Jaffa.

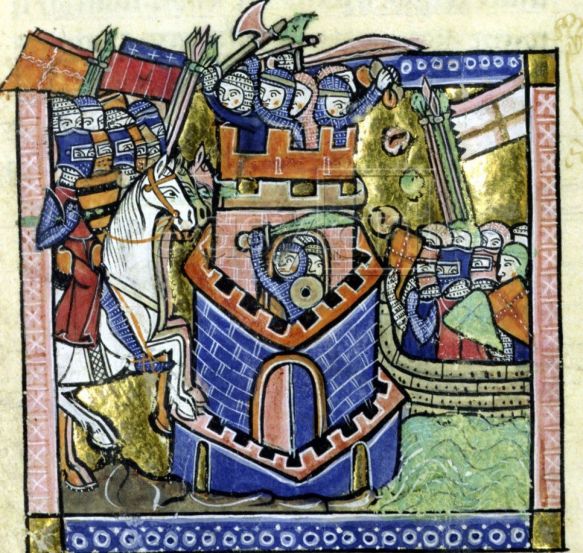

The Ascalonites delighted in the dissension between the Christians and mounted raids into the kingdom up to Arsuf. The king was furious; the court proceedings had swung the balance of power in his direction, but this military threat had to be countered. He gathered all the troops he could and besieged Jaffa. The city lies on the coast and has a small port overlooked by a castle perched on a rocky outcrop. At first, Hugh did not act alone. The treaty with Ascalon had not entirely alienated his supporters, but as the king’s troops surrounded Jaffa some began to feel that his chances of success were fading. They tried to reason with him, but Hugh would not submit—he had, after all, been found guilty of a charge of high treason and must have anticipated a severe punishment. As the count persisted in his stance, more men began to slip away and, fearful of the consequences, offered their loyalty to the king.

The Muslim world looked on with pleasure. Ibn al-Qalanisi, a contemporary Damascene writer, gleefully observed: “Reports were received that a dispute had arisen amongst the Franks—though a thing of this kind was not usual with them—and fighting had taken place in which a number of them were killed.” As Fulk sat distracted outside Jaffa, Muslim troops captured the important city of Banyas in the north of the kingdom; the civil war was beginning to exact a severe cost on the Christians.

The deadlock at Jaffa had to be broken. If at all possible, the king needed to avoid a full-scale assault. It was essential to prevent the loss of any Christian knights, or the damage to Fulk’s reputation in the Levant and across the Latin West would only worsen. Churchmen visited the king and cited the book of Matthew (12:25): “Every kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation; and every city or house divided against itself shall not stand.” Patriarch William led a delegation of nobles to mediate between the two sides. After several bitter meetings “for the sake of harmony and the greater honour of the king,” William of Tyre recorded that a compromise was reached.

Hugh and his remaining associates were sentenced to three years’ exile. After this, they could return without reproach, although in the interim the revenues from the count’s estates would be used to pay his ongoing debts and borrowings. In the circumstances this was an astounding result. Hugh had been accused of plotting to murder the king and found guilty by the High Court. He had made a treaty with Muslims, exposed the kingdom of Jerusalem to danger and loss, and openly defied the king at the gates of Jaffa. The death sentence seemed the only logical outcome—yet he had escaped with a ludicrously light punishment and, even more remarkably, he had not even been stripped of his lands. In three years he could come home to Jaffa and resume control of the most powerful lordship in the kingdom. Here—surely—we can discern the influence of Melisende. As Hugh’s most prominent ally and in her theoretical position as coruler, she must have told Fulk that to execute the count would humiliate her and create a deep and permanent division in the kingdom, starting in the royal household. The magnanimous sentence may also show that Hugh’s grievances against Fulk had some substance; such a penalty implicitly acknowledges that his case had merit. Hugh may have regarded himself as innocent, but given the way in which events had played out, he could still feel relieved at the outcome.

The matter was far from over, however. Hugh decided to pass his exile in his childhood home of Sicily. The conflict had ended in late 1134 and he now needed to wait until the New Year for passage to the West. Ships of the time were so primitive that the commercial fleets of Genoa, Pisa, and Venice only sailed the seas between March and October for fear of the treacherous winter storms of the Mediterranean. Hugh was passing time at a shop in the Street of the Furriers in the heart of Jerusalem. The cold winters of the Levant meant the production of such warm clothing was essential and this was one of many small, localized industries in this crowded district of the old city. Hugh was obviously familiar with one of the merchants named Alfanus and he had settled down to play dice—a very common pastime among medieval people. Hugh was enjoying himself and a crowd gathered around to watch and to cheer at the players’ changing fortunes. As he hunched over the table to roll the bones the count had no sense of danger at all. Suddenly, a knight from Brittany drew his sword and launched a frenzied attack, stabbing and slashing at Hugh again and again. The spectators screamed in horror, some drew their own weapons and, as the count fell bleeding to the floor, rushed forward to defend him. They jumped on the would-be assassin and captured him.

News of the assault ran through the city like wildfire; people huddled together to exchange stories and information. Who was the assailant? How badly wounded was Hugh? Gradually a dark and insistent consensus emerged: King Fulk’s hand must lie behind the deed. In his anger against the man who may have sullied his marriage bed, the man who had openly defied him, and whom he had been compelled to treat so easily, people said that the king had commissioned the unnamed Breton to murder his rival. Hugh’s cause attracted a wave of sympathy; no longer was he a treacherous outlaw. To the people of Jerusalem the atrocity showed that he was more sinned against than sinning and that their king was malicious and vindictive.

If he really was behind the plot Fulk cannot have anticipated such a public backlash in favor of the rebel. The king presumably wanted to eliminate the political and personal threat posed by Hugh; his demise would also send a message that in spite of the compromise judgment, Fulk would punish any opponents, if necessary by means outside the due process of law. He knew that Melisende would be furious, but, given the poor state of their relationship at this time, he calculated that he could weather any storm from her and, deprived of her closest ally, that she would submit.

The king needed to act to quell the outcry. Fulk ordered the captive to be brought before the High Court, the body responsible for judging capital offenses. Wisely, however, the monarch stayed away from the meeting. Given the plentiful number of witnesses there was no need for any formal hearing and the assailant did not deny the charge. By unanimous agreement the court sentenced the Breton to the mutilation of his members. Such a harsh punishment was intended to deter others from such foul acts. It meant the hacking off of the hands, the feet, and the tongue. If the guilty party survived the blood loss and the likely infection he would be condemned to a life of utter misery, crawling around, begging outside churches, eating from the floor, and facing almost certain death from exposure or starvation.

The court’s decision was relayed to the king, who asked that the man be permitted to keep his tongue. We shall never know whether Fulk engineered the plot, but if he erred in doing so he was astute enough to realize that if the man’s tongue was severed it might look as though he were trying to silence him. The Breton was tortured to reveal whether he was acting at the king’s behest, but even after the mutilation he maintained that he had been working on his own initiative and only anticipated a reward from Fulk thereafter. This confession did much to mollify the mood of the crowd and open hostility toward the king abated.

Hugh slowly recovered from his injuries. We do not know where he was treated. Given the location of the attack it is probable that he was taken to the leading medical center of the day, the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, just two hundred meters to the west of the Street of the Furriers and directly south of the Holy Sepulchre itself. There had been a hospice in Jerusalem since the days of Muslim rule when a group of Amalfitan merchants ran some form of charitable foundation. After the Christian conquest the kings of Jerusalem eagerly supported the institution and the hospital acquired a Frankish character. In 1113 it secured papal recognition as a religious order and soon grew rapidly. It was open to everyone, regardless of status, race, or religion, although the majority of its patients were the thousands of pilgrims who came to the Holy Land each year.

Hugh must have needed his wounds to be cleaned and stitched, after which he was looked after with a mixture of prayer—a vital component of medieval health provision—and close care. Each patient in the hospital had their own bed, sheets, a cloak, a woolen hat, and boots for going to the latrines. A staff of four doctors did daily ward rounds, took the pulse and examined urine. Much of the treatment centered around good basic nourishment with sugar-based drinks (from sugarcane sent down from the county of Tripoli) and meat three times a week. Some medical practices seem strange to us: for example, the meat of female cows was banned because it was deemed to promote mental instability; some patients were treated by the use of hot stones—known as lapidary—to bring out fevers. As a man of wealth Hugh may have been moved to the house of one of his supporters but the basic principles of health care would have remained the same.

Once he had convalesced the count sailed to Apulia and began to serve out his exile. It seems that a combination of his failed revolt, the legacy of his injuries, and his separation from Melisende broke Hugh’s spirit. He was received with every sympathy by Roger II of Sicily, who generously gave him the county of Gargano, but months later he died without ever returning to the Holy Land.

It was in the royal palace that the effects of the attempted murder were felt most profoundly: the botched assassination tipped the balance of power to the queen. Melisende felt outraged by the entire episode. The combination of her assertive personality and a sense of moral right precipitated a sea change in the running of both the household and the government of the kingdom. Whether the stories of her relationship with Hugh were true or not, she was incandescent at the damage to her integrity. Allies of the king, such as Rohard, lord of Nablus, who had spread rumors about Melisende’s behavior, were forced to remove themselves from the household—it was said, for their own safety. Fear of her anger caused these men to stay away from bigger assemblies, such as feast days or processions. Most pointedly, Fulk himself was completely shunned by Melisende, her kindred, and her supporters. The royal marriage was, for the time being, dead. Melisende knew that her good name had been damaged by the public nature of the dispute and she was furious with the king for giving credence to such stories. Whether Hugh was her lover or not she cared deeply for him and when he was cast into exile she was grief-stricken for her absent companion. Interestingly, the Old French edition of William of Tyre’s chronicle, written later in the twelfth century, stated that Hugh had died “por li” (for her), giving the count’s actions a chivalric aspect. He had sacrificed his life for his lady.