When MacArthur had arrived in Melbourne, he had told his aide Sid Huff to buy him a civilian hat. He hoped he might wear it if he went out for a movie when time permitted. In fact, the hat never left its box. Over the next three years, MacArthur had no time for his favorite entertainment. Running SWPA consumed all his time except for the handful of hours he snatched away for Jean and his son—while Jean and little Arthur had to adjust to their strange new surroundings of Australia largely by themselves.

For Jean, the first few weeks after arrival had meant a dizzying round of social engagements, starting with luncheons with various prominent ladies, and continuing on to cocktails and dinner virtually every night. After a time she began to complain of headaches until one day MacArthur came home for lunch and found her in bed, feeling overwhelmed by the blur of social obligations.

“What’ll I do? What’ll I do?” she kept asking him in a plaintive voice.

MacArthur called the doctor, who pronounced her physically fit. After he left, MacArthur gently closed the door and said, “If you don’t stop worrying about these things, we’ll have to write ‘What’ll I do’ on your tombstone.”

That was the end of the social whirl. Even after they moved to Brisbane and settled into the Lennons Hotel, a short walk from the nine-story office building that was SWPA headquarters, Jean and Douglas settled into the more serene domestic routine they had established in Manila, with Jean preparing the general’s lunch every day as he came back from the office to eat and enjoy a short nap, then returning to the office until early evening.

There were other headaches. For a time, they received anonymous letters threatening to kidnap little Arthur, or hinting that others were planning to do so. MacArthur refused to let it disturb their regular routine, although Sid Huff did start traveling with a revolver every time he and Jean and the boy went out. Arthur had a spell of eating troubles, sometimes taking more than an hour to finish his meals. Jean also argued that the general spoiled his son shamelessly, presenting him with gifts and little rewards no matter the occasion or how badly Arthur behaved.

Once an old friend of Sid Huff’s who owned a toy and sporting goods company sent two enormous crates for Arthur filled with everything from balloons and toy airplanes to lead soldiers and boxing gloves—with ten specimens of each.

“We mustn’t let the General know about this,” Jean told Huff in a dismayed tone. “He would give them all to Arthur tomorrow morning.” From then on, all toys and gifts were stored in a “secret closet” to which only Jean had the key—and from which both Arthur and Douglas MacArthur were barred.

MacArthur had his own peculiar eating habits. His sensitive stomach kept him away from most spicy foods, as well as alcohol, and while their three-floor suite at the Lennons had a kitchen, most dinners were brought up from the hotel restaurant. He rarely commented on what was served, beyond an occasional, “no more cauliflower” or “no more Brussels sprouts” when the appeal of that particular vegetable had begun to wane. But as he began coming home later and later to find his dinner cold, Jean took up cooking his dinner herself, as well as his lunch.

They were a tight-knit group, in the midst of a foreign country and a world at war. Along with Ah Cheu and the Bataan Gang who had survived the escape from Corregidor, no outsider understood what they had been through, or the bond that held them together—certainly not Australians. Virtually the only public appearance that Jean made in Brisbane was christening a new Australian Royal Navy destroyer, the Bataan, and the only public speech was the one she gave on that occasion:

“I christen thee Bataan, and may God bless you.”

MacArthur’s friendship with Prime Minister Curtin was genuine, as well as the source of his political leverage over SWPA. Yet he never built a warm relationship with his Australian hosts—certainly nothing like the bond that developed with the Japanese after the war. The adulation from every sector of Australian opinion that had greeted him on his arrival faded. The Australian armed forces in particular resented doing a major part of the fighting—and taking the greater burden of casualties—while having little say over where or when they fought.

Jean herself found few friends in Melbourne. She yearned for prewar Manila, and would from time to time pack and unpack footlockers for the day when they would be heading back. So did little Arthur. He had few memories of their lives in the Philippines but would sometimes tell his parents he wanted to go back to their penthouse in the Manila Hotel, just so “we don’t have to go by PT-boat,” he would quickly add.

As for the general, whatever he was doing, no matter how focused we was on the fighting in New Guinea or getting more planes for George Kenney or more LSTs for Dan Barbey or bracing himself for the next round of bruising communications with the Joint Chiefs, the Philippines were never far from his thoughts—nor were the men he had left behind.

He would remember in his mind’s eye “their long bedraggled hair framed against gaunt bloodless faces” and the tattered clothes and “hoarse wild laughter.” The battling bastards of Bataan were only a memory to most Americans, but they were real and present to MacArthur for more than three years. “They were filthy,” he wrote, “and they were lousy, and they stank. And I loved them.”

The truth was, though, that in their prison camps, they did not love him—just as they mistakenly blamed him for their miserable fate.

The Japanese plan to wreck MacArthur’s plans was code-named Operation I.; it was simple and brutal. The Japanese army and navy would join their air forces for a massive bombing campaign of Allied airfields and shipping in the Solomons, including Guadalcanal, which by the spring of 1943 was firmly in American hands, and then New Guinea.

The goal was to so cripple MacArthur’s air and sea assets that he would be unable to launch any fresh offensive for a year or more. By then, Operation I’s mastermind hoped, Japan would have consolidated its position in the Solomons chain, and Rabaul would be an impregnable fortress.

The mastermind of Operation I was Japan’s greatest war hero, Admiral Yamamoto. He had assembled 350 aircraft, both fighters and bombers, to do the job, and on April 3 he flew to the naval base at Truk in the Caroline Islands, to direct the operation himself.

Meanwhile, General Kenney was back in Brisbane and sat down with MacArthur to review his Washington trip. He found MacArthur more excited about the future than he had been at any point since arriving in Australia.

For good reason. The promised air reinforcements hugely increased the chances of a successful offensive in 1943. Barbey’s amphibious fleet was still pitifully small: just four aging destroyers turned into transports, six of the big LSTs, and thirty other landing vessels. But the Fifth Air Force now numbered 1,400 planes in addition to Australian and Dutch air units, while Halsey’s command brought on six battleships, five carriers, and thirteen cruisers, plus another 500 aircraft.

As for troops on the ground, General Blamey had under his command two U.S. Infantry divisions, the Thirty-second and the Forty-first, one marine division, and no fewer than fifteen Australian divisions. With Halsey’s seven divisions thrown in, this was beginning to look like an army ready to take on anything the Japanese could throw at it.

Still, the numbers were deceptive. Kenney and MacArthur agreed that “we were at low ebb right then as far as any decisive action was concerned,” the air force chief remembered later. Blamey’s ground forces were exhausted after the rigors of the Buna campaign; so were many of Halsey’s troops after the fierce fighting for Guadalcanal. Two regiments of the Forty-first were still working their way west along the north coast of New Guinea, but wouldn’t reach their objectives for some time. Kenney’s air forces were worn out and flying on spare parts and skimpy maintenance; instead of three fighter groups of seventy-five planes each, he was lucky if there were seventy-five fighters total that were operational.

All in all, it would be two or three months before MacArthur could be on the move again, first against Lae and Salamaua and then west toward Madang. In the meantime, Kenney’s bombers were hitting Japanese convoys as far east as Kiriwina and as far north as Kavieng on the island of New Ireland. It was only a few days after their meeting, on April 11, that Kenney and MacArthur realized something big was up, and it was headed right for Port Moresby.

After relentlessly attacking the Solomons from April 5 through April 10, Yamamoto now shifted his attention to New Guinea. This time naval intelligence let MacArthur down. They had managed to get advance warning of Yamamoto’s raids on the Solomons and Guadalcanal, but missed the timing of the “Y Phase,” or the turn to New Guinea. But Kenney’s instinct had already told him to shift his main fighter strength to protect Dobodura and Milne Bay. He made only one mistake. The main target wasn’t Milne Bay itself but his own headquarters at Port Moresby, and he had barely eight P-38s and twelve older P-39s to guard the harbor and airdromes.

At about nine o’clock in the morning on the 12th, radar picked up a large Japanese air formation coming out of Rabaul and heading for Milne Bay. Kenney’s Lightnings hit in a head-on pass and began shooting down bombers while the P-39s tangled with the Japanese fighters. The Japanese bombers dumped their bombs over Port Moresby, including several on Laloki airfield, then banked away and headed back toward Lae with the P-38s pursuing. Damage was light, as the bomb pattern had been hasty and indiscriminate. It only reinforced Kenney’s low opinion of the Japanese air force commanders as “a disgrace to the airman’s profession,” as he put it in his diary.

Despite heavy losses, Admiral Yamamoto was exhilarated. His pilots had brought back a wildly fanciful account of the damage they had done in the raids, claiming they had sunk an American cruiser, two destroyers, and twenty-five Allied transports besides shooting down 134 aircraft. Yamamoto was so delighted that he decided to take a victory tour and visit his intrepid airmen.

The message about the admiral’s visit went out on April 13. Yamamoto didn’t know it, but he had just signed his death warrant.

Dawn on April 18 brought a misty morning under a turbulent sea as two Mitsubishi Betty transport planes carrying Admiral Yamamoto and his staff made their way from Rabaul toward the western edge of Bougainville, while half a dozen navy Zeros provided escort and cover overhead.

It was around three o’clock that the pilot of Yamamoto’s plane spotted a plane on the horizon. It was a P-38 Lightning in dark khaki coloring with white stars set against dark blue circles, and it was circling over the rendezvous point assigned for the Yamamoto party. Then it was joined by another; then another and another, followed by still another.

In minutes there were eighteen P-38s clustered in the air, as if they had been lying in wait. The Japanese Zeros dove in vain to provide cover for the transports while some of the American planes rose to meet them and others, led by Captain Thomas Lanphier, swept in toward the two lumbering Bettys.

One Betty bomber swerved and crashed in the jungle, killing most of Yamamoto’s staff. The one carrying the admiral himself tried to bank and weave to avoid Lanphier’s blazing .50-caliber machine guns almost at treetop level. Then a burst from Lanphier’s plane tore open the Betty’s port engine; the plane dipped and rolled and smashed into the ground in a blaze of fire and flying debris.

The communiqué detailing Yamamoto’s entire itinerary had been intercepted by ULTRA three days before the trip. Torn between possibly shooting down the man who masterminded the Pearl Harbor attack and possibly revealing to the Japanese that their most sensitive codes had been uncovered, the Office of the Secretary of the Navy hesitated. Finally it passed the message on to SWPA, and MacArthur gave the go-ahead to intercept.

The P-38s had come from Halsey’s command; later there was debate as to whether Lanphier or another pilot from the same squadron had pulled the fatal trigger—hardly unexpected. The death of Yamamoto sent shock waves through the Japanese high command and Imperial Navy. Yet “for whatever reasons, the Japanese navy refused to consider that the Allies had broken the five-digit mainline naval operations code,” writes Edward Drea, the chief historian of decryption analysis in the Pacific war. Together with the discovery of a Japanese army list with the names of 40,000 active Japanese officers in a lifeboat that washed ashore after the Battle of the Bismarck Sea, enabling Akin’s cryptographers to match personal names to radio signals from Japanese army units, this refusal ensured that MacArthur’s intelligence remained as operationally up to date as it could be, for the foreseeable future.

In the meantime, while one admiral exited MacArthur’s life—“one could almost hear the rising crescendo of sound from thousands of glistening white skeletons at the bottom of Pearl Harbor,” MacArthur wrote years later—another admiral, an American this time, entered.

William Halsey was the navy’s version of MacArthur. They met in Brisbane on April 15, and they hit it off at once. MacArthur found the South Pacific commander “blunt, outspoken, dynamic,” while Halsey remembered MacArthur this way:

Five minutes after I reported, I felt as if we were lifelong friends. I have seldom seen a man who makes a quicker, stronger, more favorable impression. He was then sixty-three, but he could have passed as fifty. His hair was jet black; his eyes were clear; his carriage erect….My mental picture poses him against the background of these discussions; he is pacing his office, almost wearing a groove between his large, bare desk and the portrait of George Washington that faced it; his corncob pipe is in his hand (I rarely saw him smoke it): and he is making his points in a diction I have never heard surpassed.

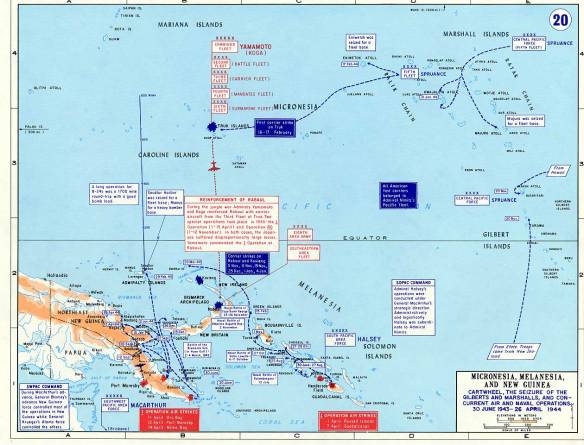

Halsey and MacArthur hammered out a plan on April 26 that they released as Elkton III. The code name, however, was CARTWHEEL, and that is the name by which it’s been known ever since.

It consisted of thirteen amphibious landings in just six months, with MacArthur and Halsey providing maximum support to each other’s efforts.

The first would take place in June, when everyone was ready and rested, with the islands of Woodlark and Kiriwina in the Trobriands, and then New Georgia in Halsey’s sector. Salamaua, Lae, and Finschhafen would be next, severing eastern New Guinea from Japanese-controlled western parts of the island.

Once Madang was in Allied hands, and the southern end of Bougainville, landings would take place at Cape Gloucester on New Britain as Halsey’s forces would knock out Japanese air bases on Buka, the island off the northern coast of Bougainville, while MacArthur’s prepared to clear Japanese resistance in the northwestern half of New Guinea.

These were insignificant operations compared to the big landings being planned in Sicily and Italy that fall, or Normandy a year later. But they added up to the step-by-step process by which Japan’s empire in the South Pacific would be dismantled. By January 1944, MacArthur and Halsey figured, they would be ready for the final assault on Rabaul—the ultimate objective for victory.

MacArthur resisted sending details of their joint plan to Washington—perhaps for fear that the Europe-obsessed Joint Chiefs would veto their ambitious thrust. He told them only that he anticipated that the first move toward Woodlark and Kiriwina would start in June. But that was too slow for Admiral King. King wanted his protégé Admiral Nimitz to begin a thrust into the central Pacific through the Marshall Islands in November, and proposed shifting the Marine First and Second Divisions, the one under MacArthur’s command and the other under Halsey’s, to help the Marshall offensive, along with two bomber groups promised to Kenney.

MacArthur’s rage boiled over in a caustic message to George Marshall, damning the entire central Pacific strategy as an unnecessary, even “wasteful” diversion from what should be the main Pacific strategy, MacArthur’s own.

“From a broad strategic viewpoint,” he wrote, “I am convinced that the best course of offensive action in the Pacific is a movement from Australia through New Guinea to Mindanao.” He added that “air supremacy is essential to success” for the southwestern strategy, where large numbers of land-based aircraft are “utterly essential and will immediately cut the enemy lines from Japan to his conquered territory to the southward.” He told the Joint Chiefs that pulling in those additional heavy bomber groups, “would, in my opinion, collapse the offensive effort in the Southwest Pacific Area….In my judgment the offensive against Rabaul should be considered the main effort, and it should not be nullified or weakened” by some quixotic thrust into the central Pacific.

King, however, was adamant. There would indeed be a central Pacific thrust led by the navy, with its main axis passing through the Marshalls and Marianas toward Japan itself, while bypassing the Philippines altogether. It was a strategy entirely at odds with MacArthur’s. Moreover, Marshall supported King, as did the other Joint Chiefs. Yet in the end King relented on the transfer of the two marine divisions, and the bomber groups. Now it was time for MacArthur to put up or shut up—that is, reveal his timetable for CARTWHEEL.

So MacArthur told them he planned to take Kiriwina and Woodlark in the Trobriand Islands on or around June 30. The advance on New Georgia would start on the same date, and in September the First Cavalry and three Australian divisions would commence operations on the Madang-Salamaua area. Meanwhile, MacArthur’s Forty-third Division would start the conquest of southern Bougainville on October 15, while the First Marines and the Thirty-second Division would take on Cape Gloucester on the southern tip of New Britain, on December 1.

In retrospect, it seems a long time to take a handful of tropical islands and jungle outposts, without even getting within striking distance of Rabaul. But MacArthur and his staff knew that the Japanese would fight them like wounded tigers at every step. The battle for Buna had shown them that the Japanese soldier was prepared to fight to the death, even for the tiniest sliver of territory. They knew that despite the blow to morale with Yamamoto’s death, the enemy still had formidable air and sea forces in the area that could strike at every move MacArthur’s forces made.

But MacArthur believed he could make CARTWHEEL work. He now understood how airpower could isolate the enemy from support by land or sea. Given enough bombers, it could neutralize the port and the airfields at Rabaul while CARTWHEEL got under way. He also foresaw how Barbey’s amphibious fleet could give his troops decisive mobility to jump from island to island with the support of Kenney’s air force and Halsey’s carriers and cruisers. And he had the battlefield commander he needed to carry out CARTWHEEL, the fourth crucial member of his team who had joined him in Brisbane in February, General Walter Krueger of the United States Sixth Army.

Krueger’s presence was part of an administrative shakeup that MacArthur had set in motion after the Papua operation, in order to give himself more direct control over the flow of troops, supplies, and other logistics for his Elkton offensive, and now CARTWHEEL. MacArthur’s USAFFE headquarters was now the administrative nerve center for all American army commands in the area—Kenney’s Fifth Air Force, the Sixth Army consisting of the Thirty-second and Forty-first Divisions, the First Marines, two antiaircraft brigades, a paratroop regiment, and a field artillery, soon to be joined by the First Cavalry and a new infantry division, the Twenty-fourth; and Army Services of Supply (MacArthur made sure it performed according to his orders, not Washington’s).

MacArthur made Krueger not only head of the Sixth Army but head of something called Alamo Force, a special tactical force that would carry out CARTWHEEL under MacArthur’s ultimate authority—and that also happened to include the exact same units as the Sixth Army. It was a subtle change, but it was not lost on General Blamey. By a bit of administrative sleight of hand, MacArthur had given Krueger and American ground forces their own independent command as Alamo Force. The redesignation of the Sixth Army as Alamo Force rendered Blamey’s title of Commander, Allied Land Forces effectively meaningless.

It was a bitter blow to Blamey, although it took him two years before he registered a formal complaint about his decapitation by flowchart. The commander in chief of SWPA, however, was determined to have a free hand for himself and his officers to develop the new combined operation formula as they saw fit. Blamey and the Australians would have their own force, New Guinea Force, to carry out the overland conquest of New Guinea as far west as Madang. But it was Alamo Force that, in MacArthur’s mind, would revolutionize modern warfare, starting in the Trobriand Islands at Woodlark.