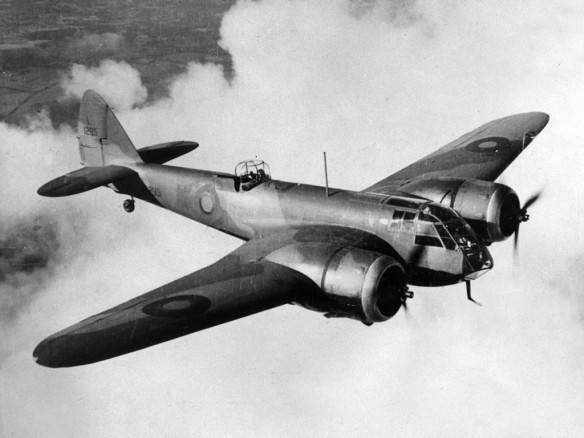

The Bristol Blenheim light bomber as flown in the daylight attack on Bremen on the 4th July.

Air Commodore Sir Hughie Idwal Edwards, VC, KCMG, CB, DSO, OBE, DFC (1 August 1914 – 5 August 1982) was a senior officer in the Royal Air Force, Governor of Western Australia, and an Australian recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest decoration for gallantry “in the face of the enemy” that can be awarded to members of the British and Commonwealth armed forces. Serving as a bomber pilot in the Royal Air Force (RAF), Edwards was decorated with the Victoria Cross in 1941 for his efforts in leading a bombing raid against the port of Bremen, one of the most heavily defended towns in Germany. He became the most highly decorated Australian serviceman of the Second World War.

In the summer of 1941, although the idea was strongly opposed by the RAF group commanders whose squadrons had suffered fearful losses in the disastrous daylight raids on the north German ports in late 1939, the British Air Staff once again began to consider the possibility of mounting daylight attacks on enemy targets. These thoughts were influenced by two events in particular: the German invasion of the Balkans in April 1941 and the assault on the Soviet Union in June, both of which had led to the transfer of Luftwaffe fighter units from the Channel coast area. The Air Staff believed that if the enemy could be persuaded to pull fighter units out of Germany to replace those redeployed from the Channel coast, then daylight penetration raids into Germany might have a chance of success. It was decided, therefore, to mount a series of strong and co-ordinated fighter and bomber attacks on objectives in the area immediately across the Channel.

These attacks, known as ‘Circus’ operations, got into their stride in June 1941 with small numbers of bombers escorted by several squadrons of fighters carrying out daylight raids on enemy airfields and supply dumps in France. Most of the bombers involved were the twin-engined Bristol Blenheims of Bomber Command’s No. 2 Group, but heavy bombers were occasionally involved; on 19 July, for example, four-engined Short Stirlings of No. 7 Squadron, strongly escorted by Spitfires, bombed targets in the vicinity of Dunkirk.

In the meantime, it had been decided that the ‘Circus’ operations were keeping sufficient numbers of enemy fighters pinned down to enable RAF bombers to make unescorted daylight penetrations into Germany, and on the last day of June Handley Page Halifax heavy-bombers of No. 35 Squadron made a daylight attack on Kiel, all returning to base without loss.

On that day, the Blenheims of No. 2 Group were also standing by to attack an important target in northern Germany: the port of Bremen, or more specifically the shipyards in the harbour area. These yards were responsible for roughly a quarter of Germany’s U-boat producion, and at a time when enemy submarines were taking an increasing toll of British shipping in the Atlantic the importance of precision-bombing attacks on such objectives could not be over-emphasized. The problem was that the yards actually producing the submarines were extremely difficult to locate at night, and although several night raids had already been carried out on Bremen there was no evidence that submarine production had been affected in the slightest. To achieve the necessary identification and accuracy an attack would have to be made in broad daylight,and Bremen was one of the most heavily defended targets in Europe, protected by a forest of barrage balloons and anti-aircraft guns of every calibre.

The dangerous and difficult mission was assigned to Nos 105 and 107 Squadrons of No. 2 Group, which was responsible for the operations of the RAF’s medium-bomber force. The two squadrons were equipped with the Bristol Blenheim Mk IV. Each Blenheim carried a crew of three: pilot, navigator/bomb aimer and wireless operator/air gunner. The last-named sat in a turret on top of the fuselage, behind two 0.303 in Browning machine guns; there were two more guns in a turret under the nose, operated by the navigator, and the fifth gun, which was fixed and fired forward, was operated by the pilot.

The Blenheims had already made one attempt to reach Bremen, on 28 June, but as they approached the enemy coast the sky ahead had revealed itself to be brilliantly blue, without a trace of cloud cover, and the formation leader – Wing Commander Laurence Petley, commanding No. 107 Squadron – had quite rightly ordered his aircraft to turn back. Petley was an old hand, and knew that if the Blenheims pressed on they would have little chance of survival without cloud to shelter in if they were attacked by fighters; in fact, they would probably not even reach the target.

Now, on the 30th, the Blenheims set out for the target once more, this time led by Wing Commander Hughie Idwal Edwards of No. 105 Squadron. Edwards, an athletic six-footer aged twenty-seven, had been born in Fremantle, Australia, on 1 August 1914, the son of a Welsh immigrant family. After his schooling he had worked in a shipping office, a steady but boring job which he left to join the Australian army as a private in 1934. A few months later he obtained a transfer to the Royal Australian Air Force, and in 1936 he was transferred yet again, this time to the RAF. The beginning of 1938 found him at RAF Station Bicester, flying Blenheim Mk Is with No. 90 Squadron; to be the pilot of what was then Britain’s fastest bomber was the fulfilment of all his dreams.

Then, in August 1938, shortly after his twenty-fourth birthday, came disaster. The Blenheim he was flying became caught in severe icing conditions, spinning down out of control through dense cloud. Edwards baled out, but his parachute fouled the aircraft’s rudder and he was only a few hundred feet off the ground by the time he managed to free himself. He suffered severe injuries in the resultant heavy landing, the most serious of which was the severing of the main nerve in his right leg, causing paralysis from the knee down.

He spent the next two years in and out of hospital and was told that he would never fly again, but he doggedly refused to accept the fact and in August 1940 he regained his full flying category. He had not long been back with his old squadron at Bicester, however, when bad luck caught him out again. Returning to base after a night-flying exercise on a black, moonless night, he found that an enemy air raid was in progress and all the airfield lighting had been switched off. Unable to land in the pitch darkness, he was forced to fly round in circles until his fuel ran out, whereupon he ordered his crew members to bale out. Then he tried to follow suit, only to find that his escape hatch was jammed, trapping him inside the aircraft. He brought the Blenheim down in a flat glide, flying as slowly as possible, and waited for the impact. A few moments later the bomber slammed through the branches of a tree, hit the ground and broke up, leaving Edwards sitting in the remains of the cockpit with no worse injury than concussion.

The accident, however, delayed the start of his operational career until February 1941, when he flew his first missions with No. 139 Squadron, which was equipped with Blenheims at Horsham St Faith in Norfolk. He at once began to make up for lost time with a series of daring raids, usually at low level, over occupied France. The casualty rate was high, and for those who survived promotion was rapid. It was not long before Edwards was posted to command No. 105 Squadron at the nearby airfield of Swanton Morley with the rank of wing commander, and by the last week of June he had thirty-five operational sorties to his credit.

Edwards had studied the Bremen defences until he knew their layout by heart, and he knew that they could not be penetrated by normal methods. There was only one way to approach and bomb the target, and that was at low level. In this way, with the element of surprise on their side, some of the attacking crews might just stand a chance of getting through. Edwards, however, was under no illusions; operating at very low level meant increased fuel consumption, and even with full tanks the Blenheims would just have enough fuel to make the round trip. If something unforeseen cropped up, such as a strong unexpected headwind on the way back, they might not be able to make it home.

The attempt of 30 June, like that of two days earlier, was doomed to failure. Fifteen Blenheims from the two squadrons took off from Swanton Morley that morning in clear weather conditions, but as they crossed the North sea it was apparent that the weather was deteriorating rapidly. The enemy coast was shrouded in a blanket of dense fog, and although the formation pressed on for several minutes through the grey wall Edwards soon knew that it was hopeless. Only two bombers had managed to keep station with him; the others were scattered in the murk and hopelessly lost. He ordered his wireless operator to tap out the recall signal, and the widely dispersed bombers came straggling back to their Norfolk base.

Early on 4 July the fifteen bombers made a third attempt. Bremen had been bombed on the previous night, and it was hoped that this attack might have caused some disruption of the German defences, giving the Blenheims an extra chance.

The bombers – nine aircraft from No. 105 Squadron and six from No. 107 – assembled over the Norfolk coast and set course in sections of three, flying at 50 ft (15 metres). Edwards’ plan was to skirt the shipping lanes near the Friesian Islands and the North German coast, turning in to make a landfall west of Cuxhaven and then making a slight detour to avoid the outer flak defences of Bremerhaven before making a fast, straight-in approach to Bremen.

Edwards was aware that however careful they were, they were certain to be detected by enemy shipping before they reached the coast. Speed and surprise were essential to the attack plan, and as the bombers approached the Freisian Islands their pilots increased speed to a fast cruise of 230 mph (370 kph), sacrificing fuel reserves in a bid to enhance the all-important surprise element. The speed increase proved too much for three of the 107 Squadron aircraft; unable to keep up, they gradually lost contact with the rest of the formation, and their pilots, realizing the folly of continuing, turned for home.

The remaining twelve thundered on, still skimming the surface of the sea. Edwards’ navigator, Pilot Officer Ramsay, reported that they were north of Cuxhaven and told the pilot to steer a new heading of 180 degrees, due south towards the mouth of the River Weser. A few moments later, as the Blenheims approached the German coastline, a number of dark shapes suddenly loomed up out of the morning haze. They were merchant ships, and in seconds they had flashed beneath the wings of the speeding bombers. The damage, however, had been done. The ships would already be signalling a warning of the Blenheims’ approach – unless, Edwards thought optimistically, the enemy crews had mistaken them for a squadron of Junkers 88s returning from a mission. The Blenheim and the Ju 88 bore a superficial resemblance to one another, and this had often led to confusion in the past, sometimes with fatal results.

The bombers swept over the coast and raced on in a thunderclap of sound over the flat, drab countryside of northern Germany. Edwards had a fleeting glimpse of a horse and cart careering into a ditch in confusion as the Blenheims roared overhead, and of white upturned faces as people in the fields waved at them, mistaking them for German aircraft. In the mid-upper gun turret, the gunner, Flight Sergeant Gerry Quinn, had no eyes for the scenery; he was busy scanning the sky above and to left and right, searching for the first sign of the enemy fighters he was certain must be speeding to intercept them.

Bremerhaven slid by off the bombers’ starboard wingtips, a dark smudge under its curtain of industrial haze. A railway line flashed under them, and Edwards picked out the town of Oldenburg away on the right, in the distance. Then, leaning forward in his seat to peer ahead, he picked out a dense cluster of silvery dots, standing out against the blue summer sky. Each one of those dots was a barrage balloon, and in a few more minutes the twelve Blenheims would have to weave their way through the middle of them, into the inferno of the flak barrage that lay beyond.

In order to present more problems to the AA gunners Edwards ordered his pilots to attack in line abreast, with a couple of hundred yards’ spacing between each aircraft. The Blenheims of 107 Squadron took up station on the left of the line, with 105 Squadron on the right. The bomber on the extreme left was flown by Wing Commander Petley, who had led the abortive raid of 28 June.

The bombers stuck doggedly to their course as they sped into the forest of barrage balloons. Whether they got through or not was largely a matter of luck; any pilot who took evasive action to miss a cable risked colliding with one of the tall cranes or pylons that cluttered the harbour area. Yet, miraculously, they all did get through, thundering over the drab grey streets, the wharves and the warehouses. All around them now, the sky erupted in fire and steel as the ships around the harbour pumped thousands of shells into their path, and the shellfire began to take its inevitable toll. A Blenheim turned over on its back and crashed into a street, exploding in a wave of burning petrol. A second blew up in mid-air as a shell tore into its bomb bay. A third, one wing torn off, cartwheeled into a group of warehouses, its bombs erupting in a mushroom of smoke and flying masonry.

On the left flank of the formation, Wing Commander Petley’s Blenheim suddenly pulled up into a climb, flames streaming from its engines. It turned, as though the pilot was desperately trying to regain control and seek somewhere to land, but a few moments later it plunged vertically into a sports field.

The rest raced on, over streets filled with panic-stricken people who scattered for shelter from the sleet of shrapnel that rained down on them from their own AA guns, a greater menace to individuals than the bombers roaring overhead. Every bomber was hit time after time, shell splinters and bullets ripping through wings and fuselage. Then they darted into the vast, sprawling docks area, each pilot selecting his individual target among the complex of factories, sheds, warehouses and wharves that lay in his path. From this height, it was virtually impossible to miss. The Blenheims lurched and jolted violently in the shock waves as the explosions of their bombs sent columns of debris hurtling hundreds of feet into the air. Clouds of smoke boiled up, obscuring the harbour, as the bombers plunged on through the outer ring of defences, all of them still taking hits.

The worst of the flak was behind them now, but the danger was not yet over. Still flying at 50 ft (15 metres), Edwards was suddenly horrified to see a line of high-tension cables directly in his path. Acting instinctively, he eased the control column forward a fraction and dipped underneath them, the bomber’s wingtip scraping past a pylon with only a couple of feet to spare. Seconds later, the Blenheim lurched as it scythed its way through some telegraph wires.

The eight surviving bombers raced for the sanctuary of the coast, skimming over woods and villages. Every aircraft was holed like a sieve, and many of the crew members were wounded. They included Gerry Quinn, Edwards’ gunner, who had a shell splinter in his knee. One Blenheim had yards of telephone wire trailing from its tailwheel. All the aircraft returned safely to base, but many of them were so badly damaged that they had to be scrapped.

For his part in leading the attack, Hughie Edwards was awarded the Victoria Cross. his navigator received the Distinguished Flying Cross, and Gerry Quinn a bar to his Distinguished Flying Medal. Members of several other crews were also decorated.

There was no denying that the Bremen raid had been a very gallant effort, with enormous propaganda value at a time when Britain was suffering serious reverses in the Western Desert and the Atlantic, but the damage inflicted on the target hardly justified the fact that 33 per cent of the attacking force had been lost over the target. Taking into account the aircraft that had to be written off later because of battle damage, this figure climbed to 60 per cent.

Despite this, on 12 August 1941 No. 2 Group launched a low-level daylight attack on the Knapsack and Quadrath power stations near Cologne by 54 Blenheims, each carrying two 500 lb (225 kg) bombs. The bombing was accurate, but ten Blenheims were shot down. On this occasion the bombers were escorted to the target by twin-engined Westland Whirlwinds of No. 263 Squadron, the only fighters with sufficient range. Fighter Command flew a total of 175 sorties in support of the raid, which was the deepest daylight penetration made so far by Bomber Command.

Hughie Edwards did not take part in this mission, having departed for Malta with Nos 105 and 107 Squadrons. He carried out many more dangerous low-level missions, in the Mediterranean theatre and in north-west Europe. Successive appointments before the war ended placed him in command of RAF Station Binbrook in 1943 – 4 and RAF Chittagong, India, in 1945. He ended the war with the VC, DSO and DFC, retiring as an air commodore in 1963. He was appointed Governor of Western Australia in 1974, and was knighted in that year. He died in Sydney on 5 August, 1982.