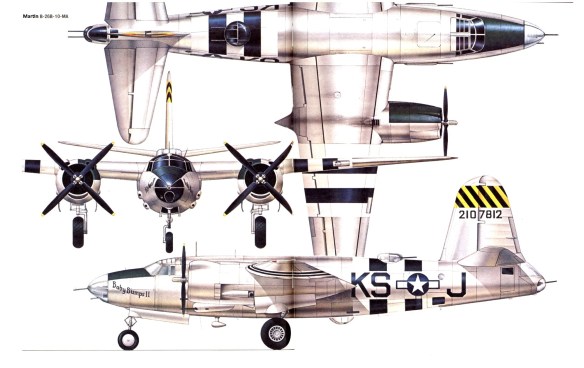

In March 1943 an important new American medium bomber, the Martin B-26 Marauder, arrived in the European theatre of operations. One of the most controversial Allied medium bombers of the Second World War, at least in the early stages of its career, the Glenn L. Martin 179 was entered in a US Army light and medium bomber competition of 1939. Its designer, Peyton M. Magruder, placed the emphasis on high speed, producing an aircraft with a torpedo-like fuselage, two massive radial engines, tricycle undercarriage and stubby wings. The advanced nature of the aircraft’s design proved so impressive that an immediate order was placed for 201 examples off the drawing board, without a prototype. The first B-26 flew on 25 November 1940, powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-2800-5 engines; by this time, orders for 1,131 B-26A and B-26B bombers had been received. The first unit to rearm with a mixture of B-26s and B-26As was the 22nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field in February 1941. Early in 1942 it moved to Australia, where it became part of the US Fifth Air Force, attacking enemy shipping, airfields and installations in New Guinea and New Britain. It carried out its first attack, a raid on Rabaul, on 5 April 1942.

The Marauder had a bad reputation, and in its early months of service it had an appalling accident rate. The problem was that it was unusually heavy for a twin-engined machine, and as a consequence it needed extra care in handling, particularly in the take-off and landing configurations. It killed a lot of inexperienced pilots before the Air Corps got used to it, and in its early days it earned a totally unjustified reputation for being a lethal aircraft. In action, however, with experienced crews, the B-26 was superb.

The first Marauders assigned to the European theatre arrived in March 1943, equipping the 322nd Bombardment Group of the 3rd Bombardment Wing at Great Saling, near Braintree in Essex. The group immediately began training for low-level attack missions under the operational control of the US Eighth Army Air Force. Some senior USAAF officers believed that assigning the B-26 to the low-level attack role in Europe was a serious mistake, arguing that the Japanese AA defences in New Guinea were nothing in comparison with the weight of metal the Germans could throw up. The flak and the fighters would tear the B-26s to pieces.

Despite these grim warnings, training continued unchecked and the first low-level mission was scheduled for 14 May 1943. The target was the Velsen power station at Ijmuiden, in Holland, which had twice been unsuccessfully attacked by the RAF. The American raid went ahead as planned; twelve B-26s set out, one aborted with engine trouble, and the remainder attacked the objective through intense flak at heights of between 100 and 300 ft (30 – 90 metres). One B-26 was destroyed in a crash-landing on returning to base; the rest all got back safely, although all had suffered battle damage. Nevertheless, the crews were jubilant; they had unloaded their delayed-action bombs squarely on the target, and they were convinced that it had been destroyed.

When reconnaissance photographs were developed the next day, however, the Americans were astonished. No damage at all had been inflicted on the power station. It appeared that the enemy had rushed special bomb disposal squads into the area to disarm the bombs, which had been fitted with thirty-minute fuses – standard practice in raids on industrial targets in Europe, in order to give workers time to get clear. The headquarters of the 3rd Bombardment Wing accordingly decided to mount a second operation against Ijmuiden on 17 May, although the commander of the 322nd, Colonel Robert M. Stillman, protested that another mission at low level against the same target was almost certain to end in disaster. HQ, however, was adamant; the mission had to be carried out, and Stillman had to do as he was told.

The group’s senior intelligence officer, Major Alfred H. von Kelnitz, also believed that a second attack on Ijmuiden would be suicidal. On the morning of the projected attack he wrote a strong memo entitled ‘Extreme Danger in Contemplated Mission’, in which he pointed out that after the RAF raids of 2 and 5 May, as well as the 322nd’s attack on the fourteenth, the Germans would be ready and waiting. ‘For God’s sake,’ he pleaded, ‘get fighter cover!’

Fighter cover was not available, however, and Lieutenant-Colonel Stillman, despite his misgivings, was forced to mount the attack without it. On the morning in question, 17 May, the group could only put up eleven serviceable Marauders. Six of these, led by Stillman himself, were to attack Ijmuiden, while the remaining five, led by Lieutenant-Colonel W.R. Purinton, carried out a diversionary raid on another power station in Haarlem.

The first Marauder lifted away from Great Saling at 10.56. The weather was perfect, with a cloudless sky and excellent visibility. The eleven aircraft formed up over the coast and headed out over the Channel at 50 ft (15 metres), keeping low to get under the enemy radar coverage. Then, with the Dutch coast only 30 miles (50 km) away, one of the marauders in the second flight experienced complete electrical failure and was forced to turn back. As it winged over on a reciprocal course, it climbed to 1,000 ft (300 metres) – just enough height to be picked up by the German coastal radar on the Dutch islands. The enemy now knew that a raid was coming in, and placed their fighter and AA defences on full alert.

The remaining aircraft flew on, making landfall a few minutes later. As they approached the coast, great geysers of water suddenly erupted in their path as heavy coastal guns opened up. Lashed by spray, the Marauders sped through the bursts and spread out into elements of two in order to present a more difficult target, increasing speed as they did so. As they crossed the coast, they were greeted by a storm of fire from weapons of every calibre, including rifles and machine-guns. The Germans had 20 mm and 40 mm multi-barrel flak guns emplaced among the sand dunes, and from these glowing streams of shells raced up to meet the bombers. There was no chance of evasive action; everything happened too quickly for that.

In the leading aircraft, Stillman opened up with his nose guns, watching his bullets churning up furrows of sand and stone as they converged on the gun position ahead of him. There was a brief, vivid impression of grey-clad figures throwing up their arms and collapsing, then he was kicking the rudder bar and yawing the Marauder to the left, his gunfire traversing the beach towards a second flak position.

The next instant, the world blew up in his face as a pattern of shells exploded all around the aircraft, knocking him momentarily senseless. The Marauder reared up, rolling uncontrollably, and Stillman came to just as it went over on its back. Out of the corner of his eye he saw his co-pilot, Lieutenent E.J. Resweber, slumped over the controls, either dead or badly wounded. Frantically, Stillman worked the controls, fighting to bring the Marauder back on an even keel. It was no use. The stick flopped uselessly in his hands; a shell had severed the control cables. The B-26 righted itself briefly, then went into another savage roll. Stillman looked up to see sand and scrub whirling past, a few feet from the cockpit canopy. He put his hands over his face. It was his last conscious action.

German soldiers on the beach threw themselves flat as the Marauder hurtled over their heads, its engines still howling. On its back, it smashed into the sand dunes at over 200 mph (300 kph), disintegrating in a great cloud of sand and smoke. Troops ran towards the debris, combing the wreckage for some sign of life. Miraculously, two men had survived the impact: Stillman and a gunner. Both men were badly knocked about, but they went on to recover in a German hospital.

Even as Stillman’s aircraft was crashing, the flak was claiming more victims. Shells chewed into the starboard wing of Stillman’s number two aircraft, and its pilot abruptly sheered off to the left to escape the line of fire, breaking right into the path of another B-26. There was a blinding flash, and suddenly the two machines were transformed into a ball of smoke and flame, shedding burning fragments as it rolled over and over towards the beaches. A third Marauder flew slap into the blazing cloud before its pilot had time to take avoiding action. Fragments slammed into it with the force of shrapnel; part of a wing dropped away and it spun down, out of control.

The wreckage of four out of six Marauders burned among the sand dunes. The two survivors of the first wave flew on bravely, intending to press home the attack, but a slight navigational error took them into the Amsterdam air defence zone and both were shot down by flak. Some crew members survived and were taken prisoner.

While the first wave was being massacred over the beaches, Lieutenant-Colonel Purinton’s flight of four Marauders managed to slip through with only relatively light damage. The formation, however, was scattered all over the sky, and by the time some measure of cohesion was re-established the aircraft had wandered several miles off course. Vital minutes were lost while pilots and navigators searched for landmarks that would help them establish a new track to the target. Nothing was recognizable in the flat, featureless Dutch landscape. At last, Purinton decided to abandon what was fast becoming a fruitless and fuel-consuming quest and asked his navigator, Lieutenant Jeffries, for a heading home.

As the Marauders swung round westwards, Jeffries gave a shout. He had seen what he believed to be the target, away to the south-west. A minute later, there was no longer any doubt: the navigator had sighted Haarlem. The problem was that the crews had been briefed to hit the target from the south, where the AA defences were lightest. Now they would have to make the attack from the north-east, running the gauntlet of heavy flak.

Undeterred, Purinton decided to press on. With flak of every calibre rising to enmesh them from all sides they swept towards the outskirts of the town. The power station was ahead of them, just where the target maps and photographs had told them it would be. One of the Marauders in the second pair veered away sharply and dropped out of formation, trailing smoke. Its pilot dropped full flap, slid over a row of trees and stalled the bomber into a field. It bounced, shedding fragments, then slewed to a stop. The crew scrambled out with no worse injuries than a few bruises.

The other three Marauders roared over the power station and dropped their bombs. Their bellies glittered palely in the sun as they turned steeply to starboard, away from the murderous flak, and sped low down for the coast. Shellfire raked Purinton’s aircraft, and with one engine chewed up by splinters and coughing smoke he knew he had no chance of making it home. He retained just enough control to slip over the coast and ditch the Marauder a few hundred yards offshore. He and his crew were picked up a few minutes later by a German launch. While they floated in their dinghy, they saw another B-26 hit the water and cartwheel violently. There were no survivors from that one.

Only one Marauder was left now. Its pilot, Captain Crane, pushed the throttles wide open and headed flat out for the open sea. He was too late. The Marauder’s rear guns hammered as three Messerschmitt 109s came streaking down from above and behind. The fighters split up, one pair attacking from either flank and the third aircraft racing towards the bomber head-on. The Marauder was flying at only 150 ft (45 metres) but the Messerschmitt was lower still, its slipstream furrowing the sea. It opened fire and shells tore into the bomber’s belly.

At the last moment the 109 climbed steeply, shooting past the Marauder and stall-turning to come down on the bomber’s tail for the kill. The Marauder’s tail gunner went on firing in short, accurate bursts, seeing his bullets strike home on the fighter’s mottled fuselage. The 109 sheered off abruptly and headed for the shore, losing height. Its last burst, however, had set fire to one of the Marauder’s engines, and Crane could no longer maintain height. He made a valiant effort to ditch the aircraft in one piece, but it bounced heavily and broke up, the fuselage plunging under the surface like a torpedo. Only the flight engineer and rear gunner managed to get out. They found a dinghy bobbing among the islands of wreckage and pulled themselves aboard. It was to be their uncomfortable home for four days before they were picked up by a friendly vessel, the only survivors of the raid to come home.

Back at Great Saling, the 322nd’s ground crews assembled at the dispersals and peered into the eastern sky for a sign of the returning aircraft. The first machine should have been back at 12.50 but that time came and went and the tension grew as the minutes ticked away. Half an hour later, with the telephone lines buzzing as operations room staff rang other airfields to see if any Marauders had made emergency landings, everyone knew the grim truth. Not one of the bombers that had set out was coming back.

Of the fifty-eight Americans who had set out on the mission, twenty-eight were dead. Twenty more, many of them wounded, were prisoners of the Germans, and two were safe. Stillman had been right: the raid had ended in disaster. But not even he had dreamed that it would be as bad as this. There was another factor, too, of which Stillman and the others had been unaware when they took off on the mission: on the previous night, 16/17 May, Lancasters of No. 617 Squadron, RAF Bomber Command, had breached the Möhne and Eder Dams in the Ruhr valley. The Lancasters’ route had taken them across Holland, and the German AA defences there were naturally still jumpy. The news of the dams raid, however, was not released by the Air Ministry until the afternoon of 17 May, after damage assessment photographs had been examined.

There was one immediate result of the 17 May disaster: no more low-level attack missions were flown by the Marauders in the European theatre. All subsequent operations were carried out at medium level, and the Marauder went on to become one of the most successful and hard-worked of all Allied medium bombers.

In September 1944 the 322nd Bombardment Group moved to France in the wake of the D-Day invasion, and operated from bases on the Continent until the end of the war. It returned to the United States in November 1945, and was deactivated in December.