British squadron in Koporye Bay in October 1919.

During World War I, both sides conducted naval operations in the Arctic to attack or defend merchant ships traveling between the western Allied states and Russia. In this theater, weather proved a formidable obstacle, with both sides calling off most operations during the winter months.

German control of the western Baltic Sea and Ottoman control of the Dardanelles that provided access to the Black Sea meant that the only practical way to ship war supplies to Russia was through that country’s Arctic ports. Arkhangelsk (Archangel) on the White Sea, the traditional shipping port via the Arctic, was closed by ice from November to May, and the Russian government developed the port of Murmansk to the east in the Kola Inlet on the Barents Sea. Although farther north than Arkhangelsk, it was warmed by ocean currents and was for the most part ice-free.

Shipping to Russia from Britain, France, and the United States via Arctic waters was immensely important to the Russian war effort. In 1915, some 700,000 tons of coal and another 500,000 tons of general cargo, mostly war supplies, traveled to Russia via this route. In 1916 that figure doubled to 2.5 million tons—25 times the amount of normal traffic in the White Sea.

In February 1915 the British dispatched the old battleship Jupiter to Arkhangelsk, in effect to act as an icebreaker. It became the first ship to reach that port in February and remained on station there until May. The Russians were concerned that the Germans might mine the White Sea approaches, and London responded to Petrograd’s requests for assistance by sending out in June a flotilla of six trawlers fitted as minesweepers. Before they could arrive, however, the German armed merchant cruiser Meteor laid 285 mines in the northern approaches. Between June and September, these mines sank or damaged nine Allied merchant ships.

When the British minesweeping trawlers arrived they immediately began operations, but one was lost to a mine within a week. Following this mining incident, the Allies instituted convoys preceded by two minesweepers. London also sent out several old cruisers and the old battleship Albemarle to act as an icebreaker to keep open a channel to Arkhangelsk in the winter of 1915–1916, and the Russians converted some trawlers to minesweepers in addition to securing a purpose-built minesweeper and several destroyers from Vladivostok.

There was little German activity in the White Sea in 1916 until September–November, when 5 U-boats of the High Seas Fleet arrived and began operations between North Cape and the Kola Inlet. By the time winter weather had forced them to suspend operations, the U-boats had sunk 34 ships, 19 of which were Norwegian. Such losses were about 3 percent of transiting vessels, small in comparison to those in other theaters.

During a conference in Petrograd in January–February 1917, Allied representatives committed themselves to sending 3.5 million tons of supplies and coal to Arkhangelsk and Murmansk that year. By that winter, British forces in the White Sea had increased to include the old battleship Glory (serving as a depot ship at Murmansk), 3 cruisers, 4 armed steamers, 2 yachts, 12 trawlers, and 4 drifters. The Russians also increased their forces in the same sea to 6 destroyers and torpedo boats, 17 dispatch vessels and auxiliary cruisers, and 26 minesweepers.

That winter the Russians also received several new English-built icebreakers. Allied shipping losses to U-boats on the Russian run during 1917 were higher than the previous year. About 20 percent of those sunk were Russian ships. They amounted to about 13 percent of round-trip voyages, although most of these losses occurred to the south, outside of Arctic waters.

Russia was for all intents and purposes out of the war with the Bolshevik seizure of power in early November 1917, although a formal peace with Germany was not signed until March 3, 1918, at Brest Litovsk. This treaty stipulated that Russian warships were to return to their ports, that Allied warships in Russian territorial waters would be treated as Russian warships (and thus to be interned by the Russians), and that the German submarine blockade of Russia would continue until a general peace settlement (i.e., a German victory over the Western Allies).

The end of Russian participation in the war did have some positive aspects for the Western Allies, as it released the goods earmarked for Russia for shipment elsewhere and also released the Allied ships involved in the trade. The British were also able to requisition some 50 Russian merchant ships aggregating about 150,000 tons.

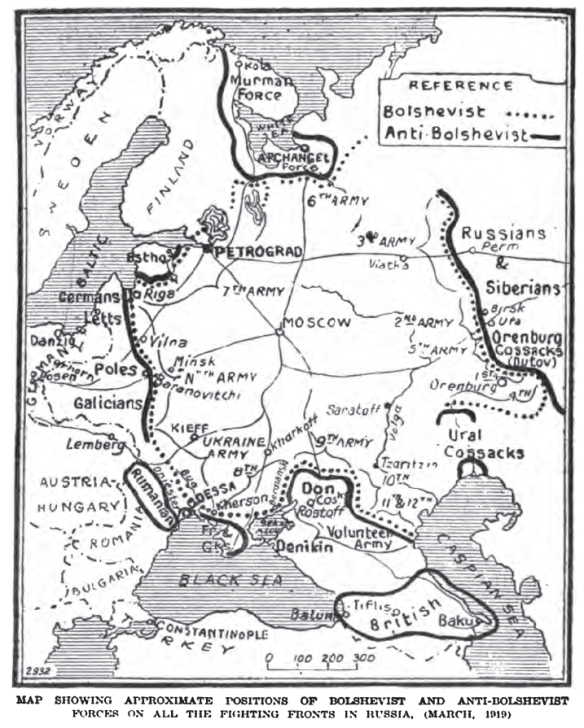

On the negative side, the British worried that substantial Allied stocks of war matériel at Arkhangelsk and Murmansk, as well as at Vladivostok in the Pacific, might fall into German hands. The motive of protecting these supplies from the Germans shifted to active intervention on behalf of the anti-Bolshevik White forces in what became the Russian Civil War (1918–1922). In July 1918, British, French, Serbian, Italian, and eventually American troops landed at Murmansk and then gradually expanded their control southward, securing Arkhangelsk in early August.

The majority of Allied naval forces committed to this activity were British, although the Americans and French each sent an old cruiser, the Olympia and the Admiral Aube, respectively. Later an improvised Allied naval force advanced up the Dvina River in a futile effort to make contact with the anti-Bolshevik Czech Legion. This Dvina Flotilla clashed repeatedly with Bolshevik forces on the river and on land.

During 1919 the Allies actively assisted the White forces, but when the Reds gained the upper hand, the Allied governments decided to cut their losses and withdrew their troops and ships. All Allied forces departed from Arkhangelsk and Murmansk in 1920.

Further Reading

Halpern, Paul G. A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994.

Hough, Richard A. The Great War at Sea, 1914–1918. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Kennan, George F. Soviet-American Relations, 1917–1920, Vol. 1, Russia Leaves the War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1956.

Messimer, Dwight R. Find and Destroy: Antisubmarine Warfare in World War I. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001.

Occleshaw, Michael. Dances in Deep Shadows: The Clandestine War in Russia, 1917–1920. New York: Carrol and Graf, 2001.