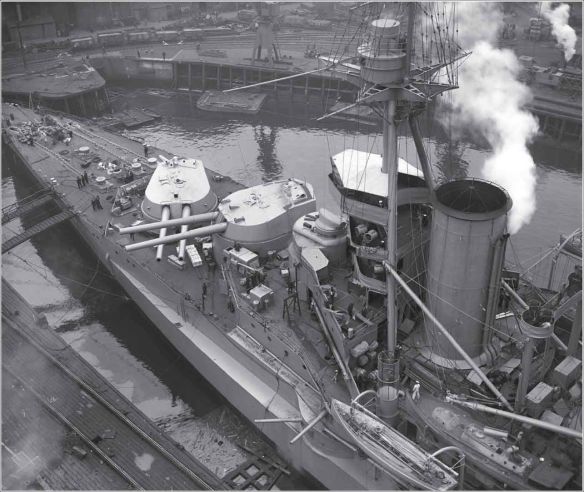

Tiger being outfitted. The photo allows the appreciation of many details of her armament and protection, including a portion of the armoured belt protruding from the port side, from ‘A’ turret aft.

A view of Tiger’s ‘Q’ turret taken in late 1917, showing the aircraft flying-off ramp and canvas hangar. Also clearly visible are a range clock and two searchlights abaft the third funnel.

While Princess Royal was being built at Vickers and the Lion construction programme was proceeding as planned, the British shipbuilding industry had the opportunity to show its abilities to Japan – a nation allied with Britain. At the same time, the British government also undertook significant political changes that had an impact on the Royal Navy and its construction policy.

Although Fisher had been replaced in January 1910 by Admiral A K Wilson as First Sea Lord, the construction programme for the Lion class would include a fourth unit. Her design, although updated, would follow that of Queen Mary and her construction was included in the next Naval Estimates. Meanwhile, the political debate regarding military spending versus social security culminated in the replacement of Reginald McKenna with Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty in October 1911. This choice, made by Asquith over other candidates, was intended to reorient the construction policy toward a more balanced approach aimed at keeping pace with German naval expansion but keeping down the costs for new types of capital ships. Churchill was deemed the right person in the right place because he had demonstrated a keen interest in the Royal Navy. This had come from his friendship with Fisher, which had endured despite their previous different opinions concerning the Naval Estimates.

From a political and strategic point of view, Churchill was determined to follow the construction policy of his predecessors. After all, the 1912 German Supplement to the Naval Law nullified an attempt to reach an agreement between London and Berlin concerning a potential retrenchment of the naval armament race. In addition, the financial pressure on Germany was beginning to create serious problems and Britain was keen to exploit this.

As far as new naval construction was concerned, this meant that the 1911-12 Naval Estimates included, in terms of capital ships, five battleships and one battlecruiser. The difference between the numbers of the two types was because battlecruisers were considered an expensive and dubious investment. Apart from that, this battlecruiser was to be the fourth unit of the Lion class, which would become Tiger. However, the design of Tiger benefitted more from the design of the Iron Duke class battleship than from the preceding Queen Mary.

Design, Construction and Cost

Before discussing the development of Tiger’s design, it is worth addressing its alleged ‘Japanese’ connection. Britain and Japan had been allies since 1902 and London was happy with Japan’s emergent navy since it might counterbalance the potential for Russian and German expansion in the Far East. Strong ties existed between the Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, which continued after Tsushima and led, in 1905, to the first renewal of the alliance treaty. Seeing itself as a key tool to pursue a policy of naval expansion in Japan’s areas of interest, the Japanese navy decided to turn to the British shipbuilding industry’s well-renowned design and construction expertise to strengthen its fleet. The friendly political situation between London and Tokyo favoured this approach, whose objective was the transfer of technology and know-how very much needed by Japan.

While discussions were under way to renew the treaty again,64 the Imperial Japanese Navy was working, through its technical department, on a design for a new class of battlecruisers, the Kongos. Thus, they decided to have Armstrong and Vickers compete against each other with the aim of building a battlecruiser with characteristics superior to the Lion class. For its part, the Japanese navy’s technical department was developing a draft design of Kongo in cooperation with the preferred British shipbuilders, Vickers, who had been building the battlecruiser Princess Royal since 1909. The overall result of the joint activities between the Japanese navy and Vickers was the award in October 1910 of the contract for the construction of Kongo. The decision was made after the thorough assessment of a battlecruiser design prepared by Sir George Thurston, then head of the warship design division at Vickers, that significantly improved Lion’s design.

Kongo’s keel was laid down in January 1911. According to the contract, Japanese designers and technicians of several branches, notably shipbuilding, machinery and armament, were sent to Vickers to supervise the construction and study the production process. Consequently, Kongo’s detailed design evolved and matured within a shipyard that had been chosen to build a new and improved Japanese battlecruiser while fitting out a slightly older British battlecruiser, Princess Royal.

Meanwhile, the Admiralty gave the DNC’s Department the task of working on what would become Tiger. Her design development took some time and evolved from seven outline proposals that were produced from July to December 1911. All proposals, identified as ‘A’ to ‘A2b’, had in common a main battery with 13.5in guns, whose layout finally discarded the amidships turret and included an after ‘Q’ turret with an increased arc of fire. Incidentally, this main battery layout, which was the main driver in the design of the whole warship, was the same as in Kongo. Unfortunately, no records seem to exist in the Admiralty proving the derivation of Tiger’s design from Kongo’s. However, it is widely known that, during the construction of Royal Navy’s battleships, battlecruisers and other types of warships a very close relationship existed between the Admiralty, notably the staff of the DNC’s Department, and all British private shipbuilders. Within such a relationship, personnel in the DNC’s Department were free to survey, monitor and inspect construction activities at these shipyards, including Vickers. Therefore, it is very likely that these personnel had several opportunities to observe and monitor the development of the Kongo’s detailed design and report back to the DNC office. It is interesting to note that the Kongo contract was signed in October 1910, while the DNC’s Department presented the first design sketches for Tiger nine months later, in July 1911. Therefore, the DNC’s Department had a lot of time to possibly improve its own preliminary sketches according to the information coming from Vickers.

Another feature of Tiger was the increase of calibre, from 4in to 6in, of the secondary battery and its placement on the forecastle deck. This allowed for better protection and arcs of fire. Kongo was similar in having 6in guns. This was because the Japanese wanted to improve the secondary battery, a consequence of lessons learned at Tsushima. The Admiralty had also long debated the efficacy of the secondary battery for its capital ships because it was mainly conceived to counter fast and powerfully-armed German torpedo boats. Thus, the decision to equip Tiger with 6in guns does not seem to have been influenced by Kongo. It is also worth noting that the Iron Duke design had 6in guns.

The most probable course of events can thus be summarised. The Japanese designers and engineers posted at Vickers were allowed access to British sketches as, probably, were Vickers’ technicians. In short, there-fore, it is safe to assume that Tiger and Kongo emerged as independent final products but with similar concepts and lines of thought.

Apart from these considerations, Tiger’s initial gun layout foresaw 13.5in superfiring turrets fore and aft. However, this solution was rejected because two pairs of closely-spaced turrets were too vulnerable in case of a lucky hit, especially on the aft pair. Therefore, the Admiralty decided to equip Tiger with a pair of superfiring turrets placed forward and ‘Q’ turret placed aft and quite far from ‘Y’ turret. This layout allowed both a broadside of eight guns and firing astern with four guns. Firing ahead remained limited because the upper turret could not fire axially due to the blast effect on the lower turret. Thus, the upper turret had a 30° firing exclusion arc, port and starboard, along its axis.

The gun layout and the provision of an aft torpedo room located well below the waterline were beneficial in respect of the mutual location of magazines and boiler rooms. Tiger had all boiler rooms placed aft of ‘Q’ turret magazine, while the engine and the condenser rooms were placed abaft this magazine. Such a machinery layout allowed all boilers to vent through three equally-shaped funnels located amidships.

In Tiger’s design, an issue that remained open after Fisher’s departure was the high-speed requirement, which led to an increase in power to 105,000shp in order to achieve 30 knots. This decision was probably also influenced by the poor performances of the Lions in their speed trials, which for Tiger meant the adoption of heavier and bulkier machinery. The Admiralty did not follow the advice to use small-tube boilers, preferring to rely upon large-tube boilers that led to a huge increase in bunker capacity and gave Tiger a radius of action comparable to the Lions. Although Tiger was designed with an almost equal provision of both coal and oil, she normally operated, at least during the First World War with much more coal than oil. The requirement for bigger machinery caused an expected increase in design displacement, which at load condition was calculated at 28,490 tons. The summary of calculated weights was as follows: hull, 9,580 tons; machinery, 5,630 tons; armour, 7,400 tons; armament, 3,660 tons; coal, 2,450 tons; general equipment, 845 tons and Board Margin, 100 tons. Adding extra coal, reserve feed water for boilers, oil fuel and other general and armament equipment, the calculated deep displacement was 33,470 tons. This meant an increase over the Lions and a huge increase – around 11,000 tons – over the first generation of British battlecruisers. The block coefficient that resulted was 0.554, making Tiger more slender than the Lions.

Tiger was designed with protection similar to the Lions, with a slight improvement to the overall armour due to the placement of 6in guns on the forecastle deck. A distinctive feature of the new battlecruiser was the aft-raked tripod mast and the suppression of the mainmast. The service boats were grouped amidships and were handled by a number of derricks and hoists that were rearranged accordingly.

The Admiralty concluded discussions regarding Tiger’s design on 19 December 1911 and approved the ‘A2b’ design. The winner of the competition among private shipbuilders was John Brown & Co, which was awarded the contract on 4 April 1912. They also manufactured the machinery. Tiger was laid down on 20 June 1912 and underwent several modifications during her construction. These in part related to improvements in internal accommodation. Externally, the funnels were modified and made as high as in the Lions, while other changes concerned armament and fire control.

Tiger was launched on 15 December 1913 and was completed in October 1914, just few months after the outbreak of the war. The cost estimated by the Admiralty was £2,100,000, a sum that probably did not include the guns. One source mentions £2,593,100, including guns, a figure that appears reliable. At her inclining experiment, Tiger’s actual deep displacement was 33,260 tons, with a mean draught of 32ft 5in and a metacentric height of 6.1ft. The angle of maximum stability was 43°, and the angle at which stability vanished differed from 71° at light condition to 86° at extreme deep condition.

Tiger’s speed trials took place on 12 October 1914 and it is probable that they were hastened because the ship was needed for war. At a displacement of 28,790 tons, and in overload machinery conditions, Tiger developed 104,635shp and recorded 29.07 knots. In normal conditions, she achieved 28.38 knots. These results did not meet the Admiralty requirements because they expected her to achieve 30 knots at an overload power of 108,000shp. A planned modification to install smaller propellers, aimed at improving speed, did not materialise because the Admiralty did not want to delay Tiger joining the Grand Fleet.

Tiger was the last battlecruiser designed while Sir Philip Watts was in charge as the DNC and was the last ship of her type built before the outbreak of the First World War. She was judged as an attractive ship because of her profile and appearance, especially when compared to previous classes of battlecruisers and battleships. Nevertheless, her derivation from the Lions, especially in terms of armour, could not overcome some weaknesses.