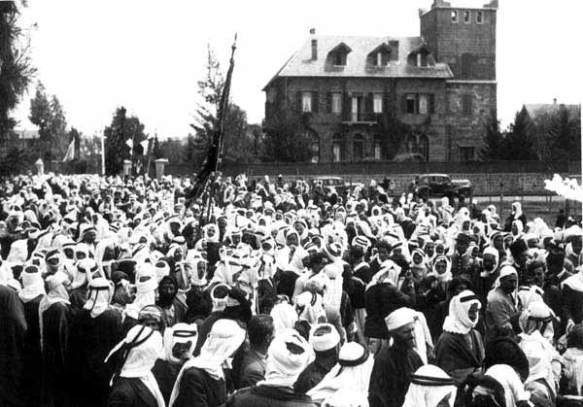

Druze warriors preparing to go to battle with Sultan Pasha al-Atrash in 1925.

General Henri Gouraud inspecting the French Army that occupied Damascus on July 25, 1920.

By 1925, after three years of relative calm, the French began to reconsider their political arrangements in Syria. Running a number of mini-states was proving expensive. High Commissioner Gouraud had completed his tour of duty, and his successors decreed the union of Aleppo and Damascus into a single state, scheduling elections for a new Representative Assembly to be held in October 1925.

After three years of political tranquility, the French relaxed their grip on Syrian politics. General Maurice Sarrail, the new high commissioner, gave pardons to political prisoners and allowed the nationalists in Damascus to form a party in advance of the elections for the Representative Assembly. Shahbandar, who served two years of his sentence before being released as part of the general amnesty, formed a new nationalist organ called the People’s Party in June 1925. Shahbandar recruited some of the most prominent Damascenes to his party. The mandate authorities responded by sponsoring a pro-French party – the Syrian Union Party. The Syrians feared France would rig the results of the elections, just as they had in Lebanon. However, the disruption to the political process came from the Druze Mountain rather than the high commissioner’s office.

Trouble had been brewing between the French and the Druzes since 1921. General Georges Catroux, another product of the Lyautey school, had drafted the French treaty with the Druzes in 1921 on the model of French Berber policy in Morocco. According to the treaty, the Druze Mountain would constitute a special administrative unit independent of Damascus with an elected native governor and a representative council. In other words, the administration of the mountain ostensibly was to be under Druze control. In return, the Druzes had to accept the terms of the French mandate, the posting of French advisors to the mountain, and a garrison of French soldiers. Many of the Druzes had deep misgivings about the terms of the treaty and feared it gave the French far too much scope to interfere in their affairs. Most took a wait-and-see approach, to judge the French by their practices. They were not reassured by what they experienced over the years that followed.

To begin, France made the mistake of alienating the most powerful Druze leader, Sultan Pasha al-Atrash. In a transparent bid to undermine the authority of the most powerful person in the Druze Mountain, the French authorities named one of Sultan Pasha’s subordinate relations, Salim al-Atrash, as governor over the mountain in 1921. This placed the French and Sultan Pasha on a collision course. When Sultan Pasha’s men released a captive taken by the French in July 1922, the imperial authorities responded by sending troops and aircraft to destroy Sultan Pasha’s house. Undaunted, Sultan Pasha led a guerrilla campaign against French positions in the mountain that lasted for nine months, until the Druze warlord was forced to surrender in April 1923. The French secured a truce with the Druze leader and avoided the dangers of putting such a powerful local leader on trial. Yet Salim Pasha, the nominal governor of the Druze Mountain, had already tendered his submission, and no other Druze leader would accept the poisoned chalice of becoming governor of the mountain over Sultan Pasha’s opposition.

Left without any other suitable Druze candidates, the French broke one of the cardinal rules of the Lyautey system, as well as the terms of their own treaty with the Druzes, by naming a French officer as governor of the mountain in 1923. If that wasn’t bad enough, the man they named as governor, Captain Gabriel Carbillet, was a zealous reformer who made it his mission to destroy what he referred to as the ‘ancient feudal system’ of the Druze Mountain, which he considered ‘retrograde.’ Druze complaints against Carbillet multiplied. Shahbandar noted ironically that many of his fellow nationalists credited the French officer with promoting Syrian nationalism by driving the Druzes to the brink of revolt.

The Druze leaders refused to accept French violations of their 1921 treaty and decided to put their complaints directly to the mandate authorities. In spring 1925 the leaders of the mountain assembled a delegation and set off to Beirut to meet the high commissioner and lodge a complaint against Carbillet. Rather than seize the opportunity to placate the disgruntled Druzes, High Commissioner Sarrail openly humiliated the great men of the mountain by refusing even to meet with them. The Druze leaders returned to the mountain in a fury, determined to revolt against the French, and looking for partners. They turned to the urban nationalists as natural allies.

Nationalist activity was gaining ground across the towns of Syria in 1925. In Damascus, Abd al-Rahman Shahbander gathered the leading nationalists in his new People’s Party. In Hama, Fawzi al-Qawuqji had created a political party with an overtly religious orientation, which he called the Hizb Allah, or ‘the Party of God.’ In this, al-Qawuqji proved one of the first to appreciate the political power of Islam to mobilize people against foreign rule. He grew a beard and visited the different mosques of Hama each night to gain support for an uprising. He established good relations with the Muslim preachers of the town and encouraged them to pepper their Friday sermons with Qur’anic references to jihad. He also gained financial support from some of the wealthy landowning families of Hama. Hizb Allah grew in manpower and financial resources. Early in 1925 al-Qawuqji sent emissaries to meet with Shahbandar in Damascus to encourage better coordination between Shahbandar’s People’s Party and Hizb Allah in Hama. Shahbandar had discouraged the emissaries from Hama, warning them ‘that the idea of a revolt in present circumstances was a clear danger harmful to the interests of the Nation.’ With the Druzes entering the nationalist cause in May 1925, Shahbandar believed the movement had reached the critical mass to stand a chance of success.

That month the Druze leadership made contact with Shahbandar and the Damascus nationalists. The first meeting was convened in the home of a veteran journalist, where the conversation revolved around the means to launch a revolt. Shahbandar briefed the Druzes on Fawzi al-Qawuqji’s activities in Hama and discussed opening several fronts against the French in a nationwide Syrian revolt. Subsequent meetings were held in Shahbandar’s house, attended by leading members of the Atrash clan. Oaths were sworn and pacts concluded in secret, and all of the participants vowed to work toward national unity and independence. It was an alliance of convenience for both sides. Shahbandar and his colleagues were only too happy to see the Druzes launch armed action in their own region, where they enjoyed far greater mobility than nationalists in Damascus and were heavily armed; in return, the Druzes would not have to face the French on their own. The Damascus nationalists promised to spread revolt nationwide, giving the Druzes the support they needed to make the first move.

The Druzes launched the revolt against French rule in July 1925. Sultan Pasha al-Atrash led a force of several thousand fighters against the French in Salkhad, the second largest town in the mountain, which they occupied on July 20. The next day, his band laid siege to Suwayda’, the administrative capital of the Druze Mountain, pinning down a large contingent of French administrators and soldiers.

Caught by surprise, the French lacked the forces and the strategy to combat the Druze revolt. Over the next few weeks, the Druze army of between eight and ten thousand volunteers defeated every French force dispatched against them. High Commissioner Sarrail was determined to suppress the revolt in its infancy so as to prevent the nightmare scenario of a nationwide uprising. He redeployed French troops and Syrian Legion forces from northern and central Syria to confront the uprising in the southern Druze Mountain. The authorities cracked down on all the usual nationalist suspects in Damascus in August, arresting and deporting men without trial. Shahbandar and his closest collaborators fled Damascus to take refuge with the Atrash clan in the Druze Mountain. And despite France’s best efforts, the revolt began to spread. The next outbreak came in Hama.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji had prepared the ground for revolt in Hama, waiting for the right moment to strike. Having watched as previous Syrian revolts against the French had surged and faltered, he believed the situation was different in 1925. There was a new degree of coordination among the opponents of French rule, between the Druzes, the Damascenes, and his own party in Hama. The Druzes had launched their revolt with devastating effect on the French. Al-Qawuqji still followed the news of the Rif War in Morocco and knew that France’s position there was deteriorating: ‘The French army had gotten entangled in the fighting with the tribes of the Rif under Abd el-Krim’s leadership. News of his victories began to reach us. We also began to receive news of French reinforcements sent to Marrakesh.’ Al-Qawuqji realized that with the French dispatching troops to Morocco, there would be no reinforcements available for the French army in Syria. ‘My preparations were complete,’ he concluded. ‘All that remained was to implement them.’

In September 1925, al-Qawuqji sent emissaries to Sultan Pasha al-Atrash in the Druze Mountain. Al-Qawuqji suggested that the Druzes escalate their attacks to draw all available French soldiers to the south. He would then launch an attack in Hama in early October. The Druze leader was willing to expose his fighters to heavy fighting against the French to secure a second front against the French in Hama, and he agreed to al-Qawuqji’s plan.

On October 4 al-Qawuqji led a mutiny of the Syrian Legion, assisted by fighters from the surrounding Bedouin tribes, with the support of the town’s population. They captured a number of French soldiers and laid siege to the town’s administrators in the government palace. By midnight the town was in the hands of the insurgents.

The French were quick to respond. Though most of their soldiers were in the Druze Mountain, as al-Qawuqji had anticipated, the French still had their air force. The French began an aerial bombardment that struck residential quarters and leveled parts of the town’s central markets, killing nearly 400 civilians, many of them women and children. The town’s notables, who had initially pledged their support to al-Qawuqji’s movement, were the first to break ranks and strike a deal with the French to bring both the revolt and the bombardment to a close. Within three days of launching their revolt, al-Qawuqji and his men had to withdraw to the countryside, leaving the French to reclaim Hama.

Undaunted by their failure in Hama, al-Qawuqji and his men carried the revolt to other towns and cities across Syria. ‘The gates of Syria’s fields were opened before us for revolt. By these manoeuvres,’ al-Qawuqji boasted, ‘the intelligence and cunning of the French collapsed before the intelligence of the Arabs and their cunning.’

Within a matter of days, the revolt had spread to the villages surrounding Damascus. The French tried to stifle the movement with displays of extreme violence. Whole villages were destroyed by artillery or aerial bombardment. Nearly one hundred villagers in the hinterlands of the capital were executed. Corpses were brought back to Damascus as grisly trophies to deter others from supporting the insurgents. Predictably, violence begat violence. Twelve mutilated corpses of local soldiers serving the French were left outside the city gates of Damascus as a warning against collaboration with the colonial authorities.

By October 18, the insurgency had reached the Syrian capital, where men and women alike joined the resistance. The men who fought were reliant on their wives and sisters to smuggle food and arms to them in their hiding places. Beneath the watchful gaze of a French soldier, one Damascene wife carried food and weapons to her fugitive husband and his rebel friends. ‘It never occurred to [the French sentry] that women were helping the rebels to escape over the rooftops or that they were delivering weapons to them under the cloaks and plates of food to contribute their part to the revolution,’ Damascene journalist Siham Tergeman recalled in her memoirs.

For the nationalist leaders in Damascus, the revolt had become a sacred jihad, and the combatants holy warriors. Some four hundred volunteers entered Damascus and managed to secure the Shaghur and Maydan quarters, driving the French administrators to seek refuge in the citadel. One detachment of insurgents made their way to the Azm Palace, the eighteenth-century vanity project of As’ad Pasha al-Azm that had been taken over by the French as a governor’s mansion, in an attempt to capture the high commissioner, General Maurice Sarrail. Though Sarrail had in fact already left his quarters, a fierce gun battle ensued, which left the old palace in flames. It was but the beginning.

The French used force majeure to defeat the revolt in Damascus. They shelled the quarters of Damascus indiscriminately with artillery from the citadel. ‘At the appointed time,’ the Damascene nationalist leader Dr. Shahbandar wrote, ‘those hellish instruments opened their mouths and belched their ashes upon the finest quarters of the city. Over the next twenty-four hours, the shells of destruction and fire consumed more than six hundred of the finest homes.’ This was followed by days of aerial bombardment. ‘The bombardment lasted from midday Sunday until Tuesday evening. We will never know the precise number of those who died under the rubble,’ Shahbandar recorded in his memoirs. Subsequent estimates put the number of dead at 1,500 in three days’ violence.

The impact on the civilian population made the insurgents bring their operations in Damascus to a close. ‘When the rebels saw the terror that gripped the women and children from the continuous shelling of the quarters, and the circling of aircraft dropping bombs indiscriminately on houses, they left the city,’ Shahbandar recounted. Though they had been driven from Hama and Damascus, the insurgents had succeeded in relieving the Druze Mountain, which for three months had borne the brunt of French repression. If the French had hoped to discourage the spread of the revolt through the use of indiscriminate violence against Hama and Damascus, they were to be disappointed. French troops had to be dispatched to all corners of Syria as the revolt spread across the country in the winter of 1925–1926.

Only after they had quelled revolts in northern and central Syria were the French able to return to the Druze Mountain, where Sultan Pasha al-Atrash still led an active resistance movement. In April 1926 the French retook Suwayda’, the Druze regional capital. After May 1926, when Abd el-Krim finally surrendered in Morocco, the French were able to divert a large number of soldiers to Syria, bringing the total French force up to 95,000 men, according to Fawzi al-Qawuqji. The Syrian resistance was overwhelmed by the French, and their leaders went into exile. On October 1, 1926, Sultan Pasha al-Atrash and Dr. Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar crossed the border into neighboring Transjordan.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji tried to continue the struggle long after the other nationalist leaders had given up. Between October 1926 and March 1927 he campaigned tirelessly to resume the revolt, but the fight had gone out of the Syrian people, who had grown cautious in the face of violent French retaliation. In his last campaign, in March 1927, al-Qawuqji managed to raise a band of seventy-four fighters, of which only twenty-seven had horses. They skirted Damascus, taking to the desert, only to be betrayed by desert tribes that formerly had supported the movement. Through guile and deception they managed to retreat to Transjordan, eluding capture but leaving their country secure in French hands.

The Syrian Revolt failed to deliver independence from French rule. The nationalist movement passed to a new leadership of urban elites who eschewed armed struggle to pursue their aims through a political process of negotiation and nonviolent protest. Until 1936 the Syrian nationalists would have little to show for their efforts.