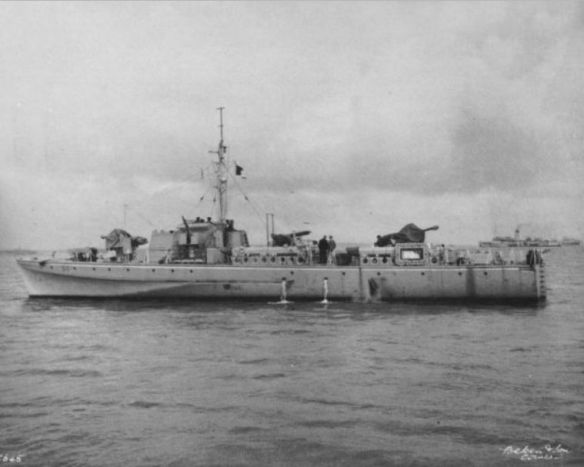

During the last year of the war, Camper and Nicholson built a series of powerful and heavily armed combined MTB/MGBs. These were based on a 1942 order for the Turkish Navy but taken over by the Admiralty and used as MGBs and blockade runners. The later series were designed with an increased beam and a spray strake since the first were found to be wet forward. Dimensions were length overall 117 ft. beam 22 ft 2½ ins, draught 4 ft 4 ins, and they displaced 115 tons. Three supercharged Packards gave a maximum speed of 31 knots and an endurance of 2,000 miles at 11 knots. Crew consisted of 3 officers and 27 men, while armament comprised a 6-pounder power turret forward, a 20mm Oerlikon on either side of the bridge and a twin 20mm amidships, another 6-pounder power turret aft, and four 18in torpedo tubes.

In the North Sea, also, Coastal Forces began to take the offensive as the arrival of both short and long MGBs enabled the MTBs to be used for the purpose originally intended, that of attacking enemy coastal shipping with torpedoes. Here again, as with the defensive measures devised against E-boats, tactics were gradually evolved after a period of trial and error. And just as the names of the individual Senior Officers of flotillas had emerged during particular periods of the war – Hichens’ MGBs at Felixstowe and in the west country, the Pumphrey-Gould era at Dover – so a new name came to the fore as a pioneer of MTB operations in the North Sea. This was Lt Peter Gerald Charles Dickens, RN (great-grandson of the novelist, son of Admiral Sir Gerald Dickens, later promoted Lt-Cdr and including among his awards the DSO, MBE and DSC).

Earlier in the war, as a regular officer, Dickens had been first lieutenant of a ‘Hunt’ class destroyer on east coast escort duties. It was during that period that he came to appreciate fully the importance of coastal convoys and their vulnerability if coastal waters were not sufficiently guarded. It was a lesson to be sharply underlined when, on 20 April, his ship, the Cotswold, was severely damaged by hitting one of several mines laid by E-boats the night before. Ironically, the MGB which picked up some of the casualties from Cotswold was the one commanded by Robert Hichens. The two men met fleetingly for the first time; later they worked closely together as Senior Officers respectively of MTB and MGB flotillas based at Felixstowe.

Dickens accepted with enthusiasm his appointment as Senior Officer of the 21st MTB Flotilla which was based at various times at Portsmouth, Dartmouth and Lowestoft, before settling permanently at Felixstowe. His first attempts to take the war to the enemy’s coast were not exactly glowing successes. This was generally the experience of the MTB flotillas at that time, acting under the vaguest of orders and with little by way of precedence to show them how to fight this unaccustomed form of warfare. The Admiralty’s most urgent consideration was in protecting Britain’s coastal shipping and little thought had been given to attacking that of the enemy. But as Dickens recently wrote in a book of his wartime experiences (Night Action, published by Peter Davies in 1974), important targets did exist, especially in the iron ore from Sweden which was vital to the German war economy and for which by far the best route was by sea to Rotterdam and thence by barge up the Rhine.

Left very much to his own devices, Dickens approached the problem from two main standpoints, firstly a scientific study of the technique of attack, in which he encouraged free-ranging discussion among his commanders, and secondly the need for discipline and training so that the tactics evolved could be carried out correctly. From the beginning, he drilled his crews in close-station manoeuvring at all speeds, so that each commander was instantly alert for signals and the slightest deviation by other boats. Even simple details were of vital importance – for instance, he insisted that commanders always carried plenty of handkerchiefs to wipe the spray from their night-glasses to keep them in good condition for viewing. As regards tactics, he saw the MTB’s role as that of a hunter stalking a quarry, in which the best method of attack was not a blind, headlong rush forward with little time for aiming correctly at the enemy, and in any case warning him of an attack, but instead a deliberate, unhurried approach which gave an opportunity to manoeuvre into the best position for firing. Even if a torpedo missed, there was still the possibility of changing course to fire from another angle. Such tactics called for a cool determination and greater degree of courage than a quick hit-and-run to get it all over as rapidly as possible, but under Dickens’ own inspiration they paid ample dividends in the end.

As with all the most resolute MTB commanders, Dickens believed in the importance of firing anything at the enemy, even small arms, although the damage they could cause was negligible. In his case, however, there was more involved than a spirit of aggression born of the desperate days when boats were sent out armed merely with .303inch Lewis machine-guns. In his analytical approach he saw that any kind of gunfire could disconcert the enemy gunners and make their own return fire more inaccurate than it might otherwise have been. However, guns were to be fired only if an MTB’s presence had been detected. On one particular occasion, Dickens’ methods probably saved the lives of himself and his crew. Before leaving on a night patrol the coxswain of another MTB which was in dock for repairs asked if he could come along in Dickens’ boat. Dickens agreed, provided the man brought a gun along with him. During an engagement some while later, Dickens found himself in the highly dangerous situation of having all his guns knocked out, one engine broken down, and surrounded by E-boats which were closing in for the kill. Suddenly, from a position just under the bridge, a single Lewis gun opened fire. It was the coxswain who had come along for the ride, his presence forgotten by Dickens. As a result of the unexpected burst of fire, the enemy’s aim was temporarily upset, their boats hesitated, and the MTB had time to get the broken engine going again and move away out of trouble.

Basing his tactics on creeping up on the enemy unobserved, to get as close as possible for a torpedo shot, Dickens also developed a system for his boats to split up in accordance with a pre-arranged plan if one was sighted. That boat would start firing and manoeuvring at high speed, not doing any particular damage but drawing the enemy’s fire and attention, giving the other boats a chance to approach quietly from another direction. If they were seen, they in turn would make a lot of noise while the first slowed down and itself tried to make an unobserved attack. With this method in mind, it became apparent that MTBs and MGBs working together would make an ideal combination. This had already been inaugurated by the Dover-based flotillas, but Dickens and Hichens developed it to an art as a result of the painstaking training of their crews. It was the basis, in fact, of Dickens’ first major success when, on the night of 10 September 1942, on board MTB.234, he led another (MTB.230 commanded by Lt J.P. Perkins) supported by three MGBs (led by Lt E.D.W. Leaf) against an enemy convoy off the Frisian Island of Texel. It was a classic combined attack by the two types of craft that later became a regular technique in Coastal Forces. While the MGBs kept the enemy escorts busy the MTBs slipped in quietly at slow speed and torpedoed and sank an armed trawler and damaged another. Less than three weeks later, on 30 September, Dickens led a similar kind of attack on an iron ore convoy in the same area and sank both the merchant ship Thule and one of the escorting armed trawlers.

The end of 1942 saw Coastal Forces gaining the ascendancy over their rivals in the North Sea and English Channel and this might have been even more marked had it not been for the particularly bad winter of 1942/43. Rough seas severely restricted the operations of the smaller craft, such as the 72½-foot Vosper second series with which Dickens’ flotilla was equipped. The time was not wasted, however. Improvements were made in the organisation of Coastal Forces on shore which went part of the way towards solving the problems that had hampered the work of Rear-Admiral Kekewich in his difficult and somewhat anomalous position. Early in 1943, Coastal Forces became the overall responsibility of two Admiralty departments, with Captain F.H.P. Maurice appointed Director of Coastal Forces Material (primarily concerned with the development and building of boats) and Captain D.M. Lees DSO appointed Deputy Director Operations Division (Coastal). A working-up base had already been established at Weymouth (HMS Bee) under Cdr R.F.B. Swinley, and not only were new crews being trained there but existing crews were seconded from operations during the winter lull to take part in the courses provided. Somewhat to their surprise, they found that they still had much to learn about gunnery, signals, torpedo drill and general tactics. All this reflected the greater degree of importance that the Admiralty had come to attach to Coastal Forces, a far cry from the early days when they were little understood and regarded very much as the poor relations of the Royal Navy. One of the most significant developments at this time, from the point of view of actual operations, was the appointment of Captain H.T. Armstrong, DSO and Bar, DSC and Bar, RN, as Captain Coastal Forces for the whole of Nore Command to co-ordinate and improve training and tactics.

Meanwhile, during those winter months Coastal Forces activities by no means ceased altogether. While the operations of the smaller craft were inevitably reduced, it was now that the larger D-boats proved their worth in being able to withstand heavier weather and with an ability to operate further afield because of their increased range. It was with this in mind that the Norwegian-manned 30th MTB Flotilla operating from the Shetlands was equipped with Fairmile ‘D’s and began a series of operations against enemy shipping in the fjords of the Norwegian coast. The new boats could now make the crossing there and back under their own power without having to be towed by destroyers as before. The flotilla was commanded by Lt-Cdr R.A. Tamber and achieved its first success in the early morning of 27 November 1942 when two boats managed to enter the Skjaergaard fjord unseen, in spite of a brilliant moon, and sank two 7,000-ton merchant ships by torpedo. The MTBs returned home unscathed, although they had to cope with a strong gale on the way back. Further successes followed, and the MTBs also took part in a number of Commando raids on enemy coastal installations. Later, the Norwegian flotilla was reinforced by a British one commanded by Lt-Cdr K. Gemmel DSO, DSC, and operations from the Shetlands continued until the last days of the war.

The Fairmile ‘D’s were also operating in greater numbers now from the east coast bases, where their increased range enabled them to hunt for enemy shipping round the Hook of Holland in places least expected by the Germans. It was Gemmel in fact, based at Great Yarmouth (HMS Midge) early in 1943 before being transferred to the Shetlands, who scored the first successes. On 9 March he led the flotilla against an enemy convoy off Terschelling and sank a 6,500-ton tanker together with two of her escorts; during the action, however, MTB.622 commanded by Lt F.W. Carr was destroyed by gunfire from German destroyers. The sight of MTB.622 sinking with all hands in a raging inferno was very much in the minds of Gemmel and his crews when the flotilla set off for the same area again three nights later. Another convoy was sighted almost at the same spot, three large merchant ships surrounded by smaller escorts. The MTBs fired their torpedoes at a longer range than was usual, nearly 3,000 yards, and hit two of the merchant ships. One broke in two and sank fast, the other caught fire first and then sank more slowly. The MTBs turned for home, the enemy being unaware of their presence from start to finish of the action.

A feature of this period of operations was an increasing degree of co-operation with other services concerned in coastal warfare, particularly with Fighter Command and Coastal Command in which short-range aircraft worked with destroyers and MTBs in attacking enemy convoys. In Nore Command, fighter-bombers of the Strike Wing of Coastal Command’s No. 16 Group occasionally went on night patrols to locate such convoys, dropping flares to act as a guide for the MTBs. In Dover, too, new tactics were developed involving co-operation with Albacores of the Fleet Air Arm and heavy gun batteries on the Kent coast. On the same night as Gemmel’s second success off the Dutch coast, 12 March, three of the Dover MTBs were lying at short notice in the harbour. The Senior Officer of the flotilla, Lt B.C. Ward DSC, was just going to bed at about one in the morning, thinking it too late for anything to happen that night, when news came that a heavily escorted German merchant ship had left Boulogne on one of the enemy’s rare attempts to make a dash through the Strait. The three MTBs, 38 (Lt Mark Arnold-Foster DSC), 35 (Lt R. Saunders DSC, RANVR), and 24 (Lt V.F. Clarkson), put to sea at once, with Ward in MTB.38. The convoy was already being fired upon by the big guns at Dover, and as the three boats reached the interception point, they found that aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm were also going into the attack. In the light of the starshell bursting overhead and with the additional help of the enemy’s tracer firing up at the planes, it was not difficult to sight the merchant ship. At that moment, a force of MGBs led by Lt G.D.K. Richards DSC arrived and engaged the escorting German patrol boats. Both Saunders and Arnold-Foster fired their torpedoes, the latter’s hitting and sinking the merchant vessel.

Efforts such as these showed that there was still a place for the short boats, especially in waters nearer home. Even further afield, where the MTB/MGB D-boats were achieving a higher proportion of successes, the smaller Vospers could still make themselves felt if handled in the right way. This was certainly the case at Felixstowe where Dickens was now Senior Officer of the 21st and 11th MTB Flotillas (the latter commanded by Lt I.C. Trelawny DSC). One such operation took place in the early hours of 14 May when four MTBs led by Dickens torpedoed and sank two German minesweepers off the Hook of Holland.

Such was the pattern of MTB operations throughout 1943, with the exception that activities in the English Channel showed a marked decline in the summer and autumn as the Germans seldom dared to run a convoy through. Three flotillas of SGBs, ‘D’ Type MGBs, and 70-foot MTBs based at Newhaven did begin to operate in a new area off the Normandy coast, although the German radar-controlled gun batteries mounted high on the cliffs made this a particularly dangerous hunting-ground.