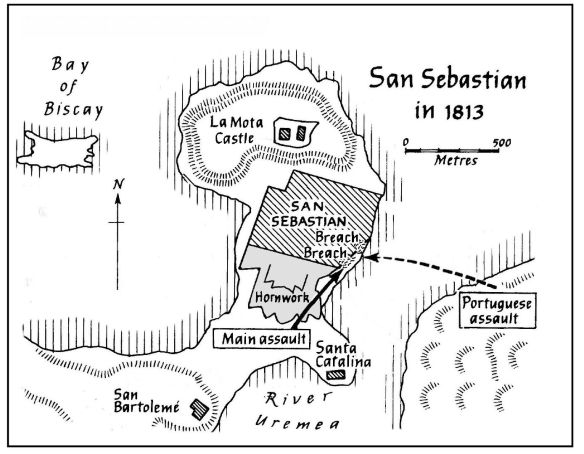

Following the Battle of Vitoria, Wellington’s army moved towards the French-held fortresses of San Sebastián and Pamplona. San Sebastián, a small coastal town with a harbour, stood on a narrow neck of land at the foot of a rocky headland called Monte Orgullo. The ancient La Mota castle stood on the summit of the hill and successive generations of military engineers had added fortifications and bastions to its defences, eventually building a wall around the town. The walls ran along the shore on the west and east sides, and the French, who had been in control of San Sebastián for five years by 1813, had added a series of earthworks, known as the Hornwork, across the neck of the isthmus. Now the 3,000-strong garrison was led by General Louis-Emanuel Rey, a resolute commander. He had sixty guns placed in strategic positions around the town walls and ships regularly brought supplies to the harbour.

Spanish troops had blockaded San Sebastián by 29 June 1813 and the siege began eight days later. Wellington was based nearby at Lesaca and after studying the fortifications with his chief engineer, Colonel Richard Fletcher, came to the conclusion that General Thomas Graham should aim to breach the south-east corner of the fortress. Once the gap had been opened up, men could attack from two directions, with some moving along the isthmus, along the foot of the wall, while the rest waded across the river Urumea. The estuary was only fordable at low tide, however, and so this would affect the eventual timing of the attack.

Six batteries were set up on the high ground next to the convent of St Bartholomew, south of the town, and they started bombarding the Hornwork and the town’s southern wall, giving support to the men digging the siege lines. As soon as redoubts had been built close to the Hornwork, two more batteries were brought forward, which started to batter the south-east corner of the walls. The engineers also supervised the digging of assembly trenches along the isthmus, so that the assault troops could get close to the walls. The work was difficult and dangerous and the French guns continued to fire at the British trenches. Colonel Sir Augustus Frazer’s battery suffered heavy casualties in front of St Bartholomew’s convent:

We were completely deluged with shot from the half-moon battery. Lieutenant Armstrong commanded the working party, who did their utmost to dig a hole for shelter from this incessant fire but to no purpose as the earth was battered down as soon as raised, and scarcely a man left unhurt. Those who escaped were assembled in the shelter of the walls, yet here was no safety as the shot flew through the windows and doors, and, rebounding off the walls, hurt many, while stones and mortar falling in every direction bruised some and blinded others.

Day after day the British gunners toiled in the hot sun firing their guns around the clock (each gun fired approximately three hundred rounds a day), chipping away at the widening gap. Many cannon-balls overshot their target and caused extensive damage among the narrow streets inside the walls.

By 22 July the breach was ready and many of the French guns had been silenced. Wellington had previously set the date of the assault for 24 July, but General Thomas Graham decided against attacking immediately, preferring to wait for twenty-four hours. Although the delay gave his men time to prepare, it also allowed the French to arrange some nasty surprises at the breaches.

When the tide was at its lowest, General Oswald’s 5th Division (General Leith returned on 30 August but was wounded two days later) and Bradford’s Portuguese brigade left the safety of their assault trenches around Santa Catharina and advanced north along the shoreline towards the breach. The garrison of the Hornwork fired at the troops as they moved along the narrow strip of land towards the breach, and casualties were increased when the town garrison threw missiles down on to the crowd of men below. The advance began to falter as they climbed the ruined wall, but when the Forlorn Hope discovered that there was a huge drop from the top of the breach into the street below, it came to a standstill. Men milled around helplessly on the rubble slope and many were killed trying to find a safe way down. Sergeant Douglas later recalled how the Royal Scots were driven back with heavy losses:

Waiting for the tide to be sufficiently low to admit men to reach the breach, it was daylight ’ere we moved out of the trenches, and, having to keep close to the wall to be as clear of the sea as possible, beams of timber, shells, hand grenades and every missile that could annoy or destroy life were hurled from the ramparts on the heads of the men. Those who scrambled on to the breach found it was wide and sufficient enough at the bottom, but at the top, from thence to the street was at least twenty feet.

It was suicidal to go on and the officers recalled the survivors, forcing them to leave hundreds of dead and injured behind them; many of the wounded were later drowned when the tide rose.

On hearing the news that the attack had failed, Wellington rode to San Sebastián to investigate (which meant that he was not at his headquarters when Marshal Soult launched his attacks on the Pyrenean passes), and met a despondent General Graham assessing his losses. He also found to his dismay that his chief engineer Colonel Sir Richard Fletcher, the architect of the Lines of Torres Vedras, was among the dead. However, he was unable to concentrate his full attention on San Sebastián as the French were pushing large forces through the Pyrenees, so the siege was stepped down until the threat had passed.

After restoring order in the Pyrenees, Wellington was able to turn his attentions once more to San Sebastián and on 8 August gave the order to renew the siege with greater intensity; this time there would be two breaches. The French had spent the past three weeks repairing the existing breach, adding a second thick stone wall behind the gap. This meant that the British needed more siege guns, new battery positions and many more assembly trenches in front of the walls.

General Graham had also taken the decision to extend his siege lines across the river Urumea in order to extend the gap in the eastern wall. He could then send troops across the estuary, bypassing the problem of restricted access along the isthmus, and doubling the number of men who could reach the walls at the same time. After his infantry had cleared the fortified convent of San Francisco, his engineers moved in and digging began on the east bank. New batteries had to be sited in the Choffre Sandhills but the work was slow and many men were killed or injured by the French guns sited on San Sebastián’s walls. The soft sand made it difficult to build revetments and tracks in the dunes and it took until 26 August to get all thirty guns into position. But once in place, they returned fire across the estuary, aiming at the temporary wall behind the old breach. Once this had been demolished, the gun crews concentrated on extending the gap and over the days that followed it had grown to more than 100 metres wide; a second smaller breach was also made. The walls could not endure the relentless bombardment. Following a reconnaissance of the breach on 29 August the decision was taken to prepare for an assault. The men would advance an hour before low tide on the 31st.

Tension mounted as the men gathered in their assembly trenches. The guns opened fire at dawn, and a cheer was raised when one lucky shot exploded a mine buried below the breach, sending a shower of rubble and dust into the air. The signal to advance was given a few minutes before 11am and the three Forlorn Hopes, formed from 750 volunteers from the 1st, 4th and Light Divisions, clambered out of their trenches and charged towards the breaches, followed by Oswald’s 5th Division and Bradford’s brigade.

The French had installed guns behind and to the sides of the breach and they fired round after round of grapeshot at Oswald’s men. As the Forlorn Hopes scaled the breaches, men on top of the walls fired muskets and threw grenades into the crowd below. Once at the top of the rocky slopes, the assault parties again faced a steep climb down the rubble to get to the street below and many were killed or wounded as they shied away from the edge. The survivors fell back out of sight of the guns and were forced to crowd together in a ditch at the foot of the breach. Once more it looked as if the assault had failed. Sergeant John Douglas of the 3/1st Regiment was lucky to escape back to the ditch:

Contrary to my expectations, I gained the trench which was a dreadful sight. It was literally filled with the dead and dying. ’Twas lamentable to see the poor fellows here. One was making the best of his way minus an arm; another his face so disfigured as to leave no trace of the features of a human being; others creeping along with the leg dangling to a piece of skin; and, worse than all, some endeavouring to keep in the bowels.

Casualties were horrendous. Most of the Forlorn Hope volunteers had been killed or injured on the rubble-strewn slopes, while Robinson’s Brigade had lost over seven hundred men, many of them cut off in the narrow streets with no means of escape.

Forty minutes after the 5th Division’s attack started, Bradford’s Portuguese brigade began wading across the estuary in two columns, moving quickly through the surf even though the water was thigh-deep in places. The French gunners had a clear sight of their targets, firing roundshot and canister into the water below, but the Portuguese forged on. One column clambered up the shore and climbed up to the smaller breach, only to find, once again, that the drop at the far side was too high and it was impossible to enter the town. The men were forced to take cover where they could find it around the breach, forming a small foothold in the shadow of the walls. The second column, seeing the problem at the smaller breach, veered south towards the main breach in the hope of finding a way into the town, but their arrival only added to the congestion in the crowded ditch.

By midday both attacks had ground to a halt and it looked as if the assault was going to fail for a second time with heavy losses. But General Graham was determined that his men would not die in vain when they were so close to entering the fortress and he ordered his artillery commander, Colonel Dickson, to fire at the curtain wall to the south of the main breach. For twenty minutes the gun crews fired over the heads of the British and Portuguese troops huddled in the breaches, causing casualties among the French defending the walls, and then the moment Graham had been hoping for came. A shell hit a large magazine, killing or stunning many of the garrison as large quantities of gunpowder exploded.

All along the siege lines gun crews heard the order to cease fire as the infantry renewed their assault. This time there was no holding Graham’s men back and they were soon clambering through the breach and scrambling into the debris-strewn streets beyond. The Royal Scots led the way and Graham later commended the men of the 1st Regiment for their bravery: ‘I conceive our ultimate success depended on the repeated attacks made by the Royal Scots.’ This time the French garrison was unable to hold back the British and Portuguese troops, who were soon swarming through the town at the start of a rampage of violence. There was fierce hand-to-hand fighting in the narrow streets as soldier and civilian alike were put to the sword. The French soldiers knew they were fighting a losing battle and many fell back towards the foot of Monte Orgullo; Lieutenant Gethin, a volunteer of the 1/11th, captured a Colour in the confusion.

General Rey led the survivors up the steep ramp into the castle and locked the gates behind them, leaving the people of San Sebastián to the mercy of the allied soldiers. Few escaped as yet again Wellington’s men went on the rampage, plundering the city below while their officers tried in vain to regain control. Subaltern Gleig was one of many disgusted by the behaviour of his comrades:

As soon as the fighting began to wax faint, the horrors of plunder and rapine succeeded. Fortunately there were few females in the place, but of the fate of the few which were there I cannot even now think without a shudder. The houses were everywhere ransacked, the furniture wantonly broken, the churches profaned, the images dashed to pieces; wine and spirit cellars were broken open, and the troops, heated already with angry passions, became absolutely mad by intoxication. All good order and discipline were abandoned.

Fires began burning out of control as strong winds fanned the flames and large parts of the town were burnt to the ground. Later on Wellington would learn that London was disgusted by the behaviour of the British troops and the damage they had done to the city, while the Spanish government in Madrid was quick to accuse him of deliberately encouraging the destruction so that it could not be used to trade with France in the near future.

As the allied officers slowly regained control of their men, their commanders were studying the next problem: La Mota castle itself, where 1,300 determined Frenchmen awaited their fate. General Rey was hoping that Marshal Soult would try to relieve his men but the latter’s attempts to cross the river Bidassoa were stopped at San Marcial (San Martzial) and Vera (Bera) on 1 September. Four days later Rey opened surrender negotiations, knowing full well that his limited stocks of water and food would not last long.

A plan was drawn up to keep intact General Rey’s reputation as a resolute commander, and on 8 September over sixty guns and mortars opened fire on the citadel to give observers the impression that he was still determined to put up a fight. When the guns fell silent two hours later the commander met senior British officers in the entrance courtyard and officially handed over control of the castle. The garrison marched out of the gates with full honours soon afterwards. After a prolonged and costly siege, San Sebastián had fallen. It had cost the lives of over 850 allied soldiers while another 1,500 had been injured in and around the city walls.

The British Troops at the Storming of San Sebastián

Hay’s Brigade 3/1st, 1/9th, 1/38th

Robinson’s Brigade 1/4th, 2/47th, 2/59th, 2 Coys Brunswick Oels

Spry’s Brigade 3rd Portuguese Line, 15th Portuguese Line, 8th Caçadores Volunteers

1st Division: Guards Brigades and the KGL Brigade

4th Division: Ross’s and Anson’s Brigades, Stubbs’s Portuguese

Light Division: Kempt’s Brigade, Skerrett’s Brigade, Portuguese Caçadores

Bradford’s Brigade 13th Portuguese Line, 24th Portuguese Line, 5th Caçadores