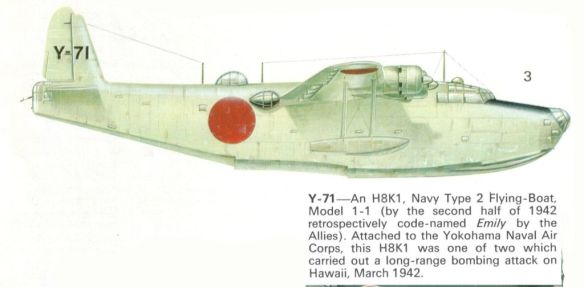

The Japanese had failed to determine whether the American carriers they hoped to lure out to their destruction were even present in Pearl Harbor. They did have a plan to find out. Nearly three months earlier, well before the fateful conference in Tokyo at which Nagano and Fukudome had capitulated to Yamamoto’s blackmail and approved the Midway plan, the Japanese had conducted a long-range reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor using two giant Kawanishi flying boats. These remarkable four-engine seaplanes, called “Emilys” by the Allies, were 92 feet long (30 feet longer than the American Catalinas) and had an astonishing range of over 4,500 miles, which meant that, theoretically at least, they could fly from the Marshall Islands to Pearl Harbor and back without stopping. Such a flight would leave no margin for error, however, and so Commander Miyo (who a month later would strenuously oppose Yamamoto’s Midway plan) suggested that their range could be extended even further by refueling them at sea from submarines. This notion hinted at using them to bomb American cities along the continental West Coast. More immediately, it provoked discussions about a second attack on Pearl Harbor, a scheme that was code-named Operation K.

Americans were very much aware of the possibility of long-range air strikes by seaplanes refueled at sea. Three months before Pearl Harbor, Hypo analyst Jasper Holmes, writing under the pen name “Alec Hudson,” had published a story in the Saturday Evening Post about American seaplanes refueled by submarines striking enemy bases three thousand miles away. In Holmes’s fictional tale, “twelve big bombers” attacked an enemy base “with machinelike precision,” wrecking an invasion convoy. Edwin Layton later speculated that Holmes’s story might have given the Japanese the idea for Operation K, but in fact the Japanese had begun experimenting with a seaplane-submarine partnership as early as 1939. After the war began, the Japanese planned to conduct a whole series of seaplane raids against Pearl Harbor—to keep track of the comings and goings of American warships, as well as to keep the Americans on edge and off balance by bombing them periodically. In the end, however, this dual objective undermined Japanese ambitions, for it focused American attention on the program and therefore compromised it.

The first (and, as it turned out, only) seaplane attack on Pearl Harbor occurred in the first week of March 1942, before Yamamoto even submitted his Midway plan to the Naval General Staff. Two Kawanishis, each of them armed with four 500-pound bombs, took off from Wotje Island in the Marshalls on March 2 and in thirteen and a half hours flew 1,605 miles to an unoccupied atoll called French Frigate Shoals, halfway between Pearl Harbor and Midway. There they refueled from two prepositioned submarines, then flew on to Oahu, another 560 miles to the southeast, arriving just past midnight on the morning of March 4. By then the weather had thickened, and visibility over the American naval base was virtually zero. The pilot of the lead plane, Lieutenant Hashizume Hisao, could see a slight glow through the cloud layer, but not much else. Thinking that he had glimpsed the outline of Ford Island in Pearl Harbor through a gap in the clouds, he dropped his bombs. His consort did the same. Then both planes headed back for the Marshall Islands, another two thousand miles and fifteen nonstop hours away.

For all the effort and expended fuel, the raid did no damage whatever. Hashizume’s four bombs fell on the forested slopes of Mount Tantalus behind Honolulu, and the four from the other plane fell into the water near the entrance to Pearl Harbor. Moreover, the heavy cloud cover meant that Hashizume could not report with much certainty about what ships were or were not in the harbor, though he claimed to have seen at least one carrier.

The most important consequence of this raid was that it drew Nimitz’s attention to the threat. Nimitz asked Layton how the Japanese had managed to drop four bombs on Oahu (the four that fell into the harbor had disappeared altogether, and no one was even aware of them until after the war). Layton was fairly sure that they had done it with seaplanes refueled from submarines, and he told Nimitz about Jasper Holmes’s story in the Saturday Evening Post. Layton also speculated that the Japanese had used French Frigate Shoals to refuel. As a result, Nimitz stationed an American seaplane at French Frigate Shoals, sending the USS Ballard, a destroyer recently converted to a seaplane tender, there in late March.

For a variety of reasons, the Japanese did not continue their planned series of raids on Hawaii, but when Yamamoto sought reassurance that the American carriers were still in Pearl Harbor on the eve of the Battle of Midway, his staff suggested a reprise of Operation K. Again Hypo was able to alert Nimitz to the Japanese plan. On May 10, Layton informed Nimitz about an intercepted message that referred to the “K campaign” involving both aircraft and submarines, and three days later he reported that “the K campaign [was] underway.”

The Japanese committed six submarines to the project: two filled with aviation fuel, two as radio beacons, one as a plane guard, and one as a command boat. The first of them, the I-123 commanded by Lieutenant Commander Ueno Toshitake, arrived at French Frigate Shoals on May 26. When Ueno approached the atoll and peered into the lagoon through his periscope, he saw a U.S. Navy warship anchored there. When the two fuel-laden submarines showed up the next day, the American warship was still there. In fact, another converted seaplane tender, the Thornton, had joined her. The submarines were in no position to challenge them—the Type KRS submarine had been designed as a minelayer and did not have torpedoes or torpedo tubes. A surface attack would be suicidal, since each of the American surface ships boasted four 4-inch guns. Besides, the whole point of Operation K was stealth. The Japanese could only hope that the Americans would simply go away. Ueno radioed the circumstances back to his superior in the Marshalls and received orders to wait one more day. On May 31, several Catalina PBYs landed in the lagoon to join the tenders. Informed of this, Vice Admiral Tsukahara Nishizo cancelled Operation K. There would be no reconnaissance of Pearl Harbor before the Battle of Midway; the Japanese would simply have to trust that the American carriers were still there. Of course, the day before that, on May 30, the Yorktown had left Pearl Harbor to join Task Force 16 at Point Luck.

The second thing that went wrong that week was that the Japanese were tardy in establishing the submarine cordons that were supposed to track the American carriers as they left Pearl Harbor in response to an attack on Midway. Seven submarines, constituting Cordon A, were to occupy a north-south line west of Pearl Harbor. Six more would constitute Cordon B north and east of French Frigate Shoals. Another six would occupy a line near Midway. The subs were to report the carriers’ movements and then inflict whatever damage they could as a prologue to the main event. All three cordons were to be established by June 2. They got a late start out of Japan, however, and also lingered a day in Kwajalein, so that they were late in arriving. In addition, several subs were delayed by their involvement with the aborted Operation K. As a result of all this, only one sub made it into position by June 2; the others did not arrive until June 4. By then, the American carriers were nearly a thousand miles to the north. Watanabe Yosuji, Yamamoto’s loyal logistics officer, blamed the submarine commander Captain Kuroshima Kameto. Watanabe insisted that Kuroshima was simply not energetic in pursuit of his duties. Whatever the merits of that assertion, Yamamoto and Nagumo steamed eastward unaware that the American carriers—their principal quarry—had already flown the coop.

On June 2, Yamamoto’s battleships and Nagumo’s carriers, fighting their way eastward through rough seas, were blanketed by a fog so thick that the ships had to use searchlights to find one another in the formation. On the one hand this was a stroke of luck, for it hid them from the prying eyes of American long-range search planes from Midway. On the other it also prevented Nagumo from sending out search planes of his own, and it was stressful for the entire formation to execute the required zigzag course (to confuse American submarines) while maneuvering through a fog. A witness on board Akagi recalled seeing Nagumo and members of his staff on the bridge staring “silently at the impenetrable curtain surrounding the ship, … each face tense with anxiety.” Nagumo may indeed have been anxious. He had heard nothing from the submarines other than one report from I-168 off Midway, which relayed the information that, although the Americans were conducting intensive air search operations, the only vessel in sight was a picket submarine off Sand Island. Nagumo had to assume that no news was good news.