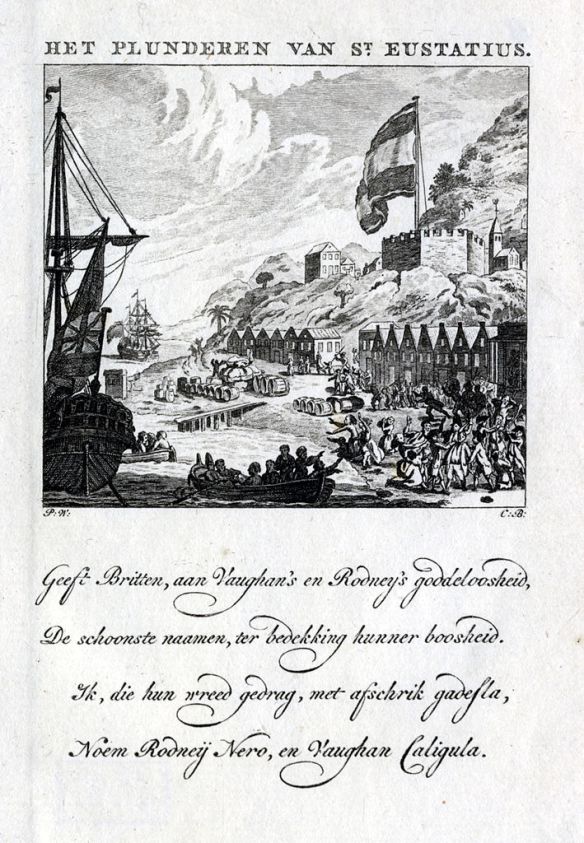

Dutch engraving denouncing the looting of the island of St. Eustatius in 1781 by the Royal Navy (Caribbean). Admiral Rodney is compared to Nero and General Vaughan is treated Caligula.

By the time Lord Cornwallis was chasing Nathanael Greene across the Carolinas and Benedict Arnold, in red regimental coat, was laying waste to Virginia, the war in the rebellious colonies had been reduced, for England, to one detail on a larger canvas of trouble. While those events so familiar to students of American history were unfolding—the fall of Charleston, the Battle of Monmouth, Arnold’s treason—England found itself in a wider war being waged across much of the rest of the world. This conflict played out in Europe, the Mediterranean, the East Indies, and the West Indies, and it was contested chiefly at sea.

Though the French in 1779 had come within a few miles of landing troops on British soil and were scheming to do so again in 1781, they had no intention of taking and occupying England. Their object, rather, was to inflict massive damage and instill fear in the British homeland. This was not a war of grand armies contesting the control of European soil, nor of nations seeking to subjugate nations. It was a war not for power but for colonies, which is to say, for wealth. England and France fought for territorial control in Africa and India, for rich plantation islands in the West Indies, and—almost incidentally—to determine whether the British colonies in North America would gain independence.

It had taken General George Washington long years to fully appreciate the role of sea power in the war he was fighting, but by 1781 he had learned the lesson well. It was in the summer of 1780 that he had written to the Comte de Rochambeau concerning “a decisive naval superiority” being “a fundamental principle, and the basis upon which every hope of success must ultimately depend.”

The British and French ministries needed no ghost come from the grave to tell them that, of course. They had been maneuvering their big fleets around the oceans even before the French had officially weighed in on the side of the Americans. In the English Channel, off the coasts of France and Spain, in the West Indies, and even, occasionally, off the coast of America, the fleets had been contesting for mastery of the sea and the potential conquests that would come with it.

Just as the land war saw ongoing changes in command and strategy, so too did the war at sea evolve as the conflict dragged on. By 1780, England stood alone. All of maritime Europe was either actively at war with Great Britain or part of an Armed Neutrality that jealously guarded its countries’ shipping against British incursion. France was focused on protecting her possessions in the West Indies and taking any of England’s territories she could, while Spain was primarily concerned with taking back Gibraltar and Minorca.

With so much depending on naval superiority, the British Parliament in the autumn of 1779 voted to spend 21 million pounds on the navy—a princely sum in the day—and authorized the recruitment of eighty-five thousand sailors and marines. The Earl of Sandwich, First Lord of the Admiralty, suggested for the command of the Leeward Islands Admiral Sir George Brydges Rodney. Rodney was a temperamental sixty-one-year-old veteran of the Seven Years’ War, during which he had distinguished himself in action even if he did show a more than proper interest in acquiring prize money. Prior to the war in America, he had been hiding in Paris from creditors, having run up gambling debts he could not pay. He was eager to get into the war and equally eager to find a means of climbing out of debt.

In December 1779, Rodney sailed with a small fleet under his command and a larger contingent of ships from the Channel Fleet. He was bound for the West Indies, but first he was ordered to lift the Spanish siege of Gibraltar. After decimating an inferior Spanish fleet, he landed troops and badly needed supplies for the beleaguered garrison there. Rodney credited his victory in part to the fact that his ships were copper-bottomed, which allowed him to catch the fleeing Spaniards. Without that not-so-secret weapon, he wrote, “we should not have taken one Spanish ship.”

He then sailed with his five ships of the line to the West Indies, arriving at St. Lucia on March 27, 1780. There he took command of a fleet of twenty-one ships of the line, though many of them were in poor shape, having suffered the ravages of hurricanes and the rot that so quickly set in to wooden ships in the tropics. Throughout the summer of 1780, Rodney and the French fleet maneuvered against one another, meeting in a series of desultory battles that left the strategic situation largely unchanged.

In August, Rodney received word of Chevalier de Ternay’s arrival at Newport with seven ships of the line and the Comte de Rochambeau’s troops. Believing that “His Majesty’s Territories, Fleet and Army in America were in imminent Danger of being overpower’d by the Superior force of the public Enemy. . . I flew with all dispatch possible. . .” to New York with ten ships of the line. There he found that although Vice-Admiral Arbuthnot had for a brief time been inferior in strength to the French fleet, the timely arrival of Admiral Thomas Graves’s squadron, of which Rodney was unaware, had since given him a slight advantage over de Ternay.

Arbuthnot was extremely resentful of Rodney’s assumption of command in New York, but there was little he could do about it, Rodney being senior in rank. Arbuthnot contented himself with sulking with his squadron at the east end of Long Island and making life difficult for Rodney in a hundred petty ways, just the behavior that had been driving Sir Henry Clinton to distraction for months. In any event, Rodney’s tenure in North America was only long enough to convoy General Alexander Leslie and his twenty-five-hundred-man contingent from New York to Virginia, and by December and the end of the hurricane season he was back in the West Indies.

The situation that greeted him on his return was not good. A hurricane on October 10 had destroyed many of the ships stationed there as well as the naval stores needed to repair them. His own squadron had suffered damage in a gale during the passage from New York, and now his entire fleet was reduced to nine ships of the line, not one of them with spare rigging or sails. Early in the new year, however, he was reinforced by a squadron of eight ships of the line under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood.

Hood had recently celebrated his fifty-sixth birthday when he joined Rodney in Barbados. He had entered the navy as a “captain’s servant,” and in 1744 he and Rodney had served together as midshipmen aboard the Ludlow Castle. By 1780, Hood had had a long and honorable, if not overly distinguished, career. He also had considerable experience on the North American station, having commanded several vessels there and served as commodore and commander-in-chief from 1767 to 1771.

In 1778, Hood had been appointed commissioner of Portsmouth Dockyard, a post that was generally the last before an admiral was ushered out of active service. As it happened, however, the Earl of Sandwich was having a hard time finding flag officers to command England’s various squadrons at sea. Many did not want to serve under Sandwich’s corrupt administration. Others did not care to find themselves second to the irascible Rodney. But Hood was willing. He received a special promotion to Rear Admiral of the Blue in September of 1780 and was sent with a squadron to join Rodney.

Despite this inauspicious entry to flag rank, Hood would prove an able commander in a career that would last another fourteen years and include heroic service during the French Revolution. When he retired from the sea in 1794, Horatio Nelson called him “the best officer, take him altogether, that England has to boast of; great in all situations which an admiral can be placed in.”

In December of 1780, England declared war on Holland, that country having secretly supported the Americans since the early days of the Revolution. In January 1781, Rodney received orders to take the Dutch territory of St. Eustatius, a tiny, undefended volcanic island in the Caribbean. Though only 8 square miles, St. Eustatius had become a major depot in the Caribbean where French, Spanish, and even, quite illegally, British merchants traded, often with American merchants and often for the supplies that were vital to the American war effort. It was a fabulously lucrative trade, and one that had long galled the British. Now they could put a stop to it.

Rodney’s fleet arrived off the island on February 3, before word had even arrived that England and Holland were at war. The governor wrote that on finding the British invading his island, his “surprise and astonishment was scarce to be conceived.” St. Eustatius would have been in no position to defend itself in any event.

The capture of the island sent Rodney and the British military commander in the West Indies, General Sir John Vaughan, into a feeding frenzy. For three months, amid howls of protest throughout the Caribbean and in London, they inventoried and sold off loot calculated in the many millions of pounds, which they considered their spoils of war. Eventually the two would be censured for their actions, but in the meantime naval and military activity in the West Indies ground to a halt while the two leaders counted their money.