The opening of the 1781 campaign season in the North did not look terribly promising for the Americans. The Continental Army was in as poor a state as it had been at any time in the five and a half years of its existence. Washington, who had discontinued his diary in 1775, resumed it in May 1781, setting the stage in the preface:

[I]nstead of having everything in readiness to take the Field, we have nothing and instead of having the prospect of a glorious offensive campaign before us, we have a bewildered and gloomy defensive one – unless we should receive a powerful aid of Ships – Land Troops – and Money from our generous allies and these, at present, are too contingent to build upon.

The failure of Chevalier Destouches to capitalize on his advantage over the British fleet at the Battle of Cape Henry, and the consequent collapse of the expedition against Arnold, had left Washington without a strategy for the spring of 1781.

Rochambeau tried to put the best face on the French failure at sea. “The Last engagement of the Chevalier Destouches has shewn to your Excellency the uncertainty of Success in naval fights and of combined operations upon that element,” he wrote soon after the fleet returned to Newport. “We must not flatter ourselves that our successes will be greater, as long as we have not a decided Superiority.”

The French general had more experience with combined army-navy operations and could likely accept their uncertain outcome with more equanimity than Washington. Nor had Rochambeau been suffering the stress and deprivations of six years of warfare, so it was hardly a surprise that such fatalism came easier to him.

But Washington was learning. Since France had joined forces with the Americans, he had seen his hopes for a dominant French fleet dashed again and again. He had finally come to understand that he could not win the war without naval superiority, and the French had the ability to provide that superiority, but every time they promised it they came up short. It was enormously frustrating.

The commander-in-chief once again put on a good show of public understanding, but he gave vent to his irritation in private. Even before the Battle of Cape Henry had played out, he wrote to Lund Washington, his cousin and the Mount Vernon overseer, “It is unfortunate; but this I mention in confidence, that the French Fleet and detachment did not undertake the enterprize they are now upon, when I first proposed it to them.” Had they done so, Washington felt, Arnold’s capture would have been “inevitable.”

Unfortunately, this letter was intercepted by the British and published in the April 4 edition of the Rivington Gazette, a copy of which made it to Rochambeau’s hands. Rochambeau wrote Washington asking if he was in fact the author of the letter and including a polite but firm reminder of the sequence of events and the fact that the first small squadron under Captain de Tilly had been sent on the request of the Congress and the State of Virginia. He pointed out that the deployment of the larger squadron had taken place about as swiftly as it could have considering the weather, the shortage of supplies in Newport, and the presence of the British fleet.

Polite as Rochambeau’s letter was, Washington must have burned with humiliation when he read it. “I assure your Excellency,” he wrote to Rochambeau, “that I feel extreme pain on the occasion of that part of your letter. . .” that touched on his comments regarding the fleet. While acknowledging authorship, the commander-in-chief averred that it was a private letter written before he knew all the facts of the case, both of which were true.

In truth, Rochambeau privately agreed that Destouches had not moved as expeditiously as he might have. He replied to Washington that he “wrote only to have the means of smothering up that trifle, at its birth.” He assured Washington that Destouches knew nothing of the letter and that he would try to keep it that way.

Word of the Battle of Guilford Courthouse first reached Washington’s headquarters at the end of March. Details were initially scant, but like most military people reading between the lines of Cornwallis’s “victory,” Washington divined the truth of the matter. Though Cornwallis had held the field, it was clear that the number of killed and wounded his army had suffered would “retard and injure essentially all his future movements and operations.” It was not yet clear, however, what impact that would have on the strategic picture in North America. Only hindsight would reveal that Guilford Courthouse was the beginning of the end of the American Revolution.

The correspondence between Washington’s headquarters at New Windsor and Rochambeau’s at Newport continued to flow unabated, and the chief subject was, of course, what the combined armies might do next. Washington still had his sights on Clinton and New York City. To prepare for such an offensive, Rochambeau suggested moving his troops to the Hudson River, but Washington demurred, not feeling they were ready to begin such an undertaking. If Rochambeau left Newport, three thousand militiamen would have to be mobilized to protect the fleet at anchor there. Feeding, housing, and paying militia was expensive, and deploying them tended to hurt recruitment efforts for the Continental forces. As Washington, first among equals in the Virginia aristocracy, explained to the French count, “the Militia service is preffered by the peasantry to the Continental.” Washington did suggest that Rochambeau make it seem as if he was going to march toward New York, which would likely prevent Clinton from sending any more troops to Virginia.

Other possibilities were raised. John Hancock and the Massachusetts legislature called on Rochambeau and Destouches to send an expedition to Penobscot Bay in the district of Maine (then part of Massachusetts). In 1779, the British had established a fort in Castine as a secure harbor in New England and a place for Loyalist refugees to resettle. An American expedition that summer to dislodge the British had met with disaster, thanks mostly to a lack of cooperation between the commanders of the army and navy. Three Continental navy men-of-war and sixteen armed vessels from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and the privateer ranks—344 guns in all—had hovered ineffectually off Castine until a superior British squadron sailed up the bay, cutting off all hope of retreat and annihilating the fleet. Though the fort had never posed a great threat, it was a thorn in Boston’s side that Hancock would have liked removed.

The French supported the idea, but Washington was lukewarm, suggesting that it was too risky to divide the French fleet by sending ships of the line and that frigates should be deployed instead. He also pointed out that militia were not to be found in great numbers in the wilds of Maine and that Rochambeau should use “such a force from your army as you deem completely adequate for the speedy reduction of the post.”

Destouches did not think the attack could be carried out without employing ships of the line, but, rather than disagree with Washington, he canceled the expedition. The French Admiralty had ordered Destouches to send his transports to the West Indies, and they were supposed to have sailed in February. The acting admiral dragged his feet until mid-April, not wanting to deprive Washington and Rochambeau of the ability to move troops by sea, but finally he could hold out no longer, and on April 18 he sent the ships south.

When Washington wrote in his diary that French aid was “too contingent to build upon,” he was touching on one of the chief problems both he and Rochambeau faced when considering strategy. Neither of them knew what the French government would be sending to North America in the way of troops, ships, and money, and, until they did know, it was hard to plan. On May 7, as an ailing Major General Phillips was receiving word at last that Cornwallis was on his way to Virginia, the answer came.

A storm was lashing New England with high winds and driving rain that day when the frigate Concorde plunged her way into Boston Harbor with topsails close reefed. Forty-two days out of France, she turned up into the wind and let her anchor go.

Concorde was the ship for which Rochambeau had been so eagerly waiting. She had on board one million livres in hard currency, together with letters and dispatches from the ministry in Paris, and she carried Jacques-Melchoir Saint-Laurent, Comte de Barras, the sixty-year-old admiral sent out to take command of the fleet at Newport after the death of de Ternay. Also on board was the Vicomte de Rochambeau, the general’s son. The previous autumn he had been sent to Versailles to report on the situation in North America and to bring back orders, and now he had returned.

It was not until ten o’clock the following day that a courier rode up to Rochambeau’s headquarters at Newport with word from the French consul of the arrival of Concorde with Barras and Rochambeau’s son. The general immediately penned a note informing Washington of the arrival and indicating that he expected Barras and his son to be in Newport the following day, adding, “your Excellency may well think that I wait for them with great impatience.” Rochambeau knew that his son and Barras would have with them the information the generals needed to plan the summer’s campaign. “I believe it will be necessary as soon as we have received our Dispatches that we should have a conference with your Excellency,” he wrote. “[Y]our Excellency may, however fix upon the place for our meeting.”

Washington chose Wethersfield, Connecticut, just south of Hartford and nearly equidistant from both headquarters. The date would be Monday, May 21. Washington would bring with him General Henry Knox and General Louis Duportail, a French engineer serving with the American army.

When Barras and Rochambeau’s son arrived at Newport, Rochambeau found that the young vicomte had some good news and some not so good. A convoy of about fifteen ships was following in the wake of the Concorde, carrying with it even more hard currency as well as six hundred replacements for the infantry. Those six hundred, however, were all that Rochambeau would be getting. The second division that had been promised him when he had sailed for America the previous year would not be coming. Instead, the French effort that year would be focused on the Caribbean. Like the British, the French viewed the West Indies as vastly more important than the thirteen newly minted states.

There was one other bit of news, however, which Rochambeau likely greeted most enthusiastically of all. The Comte de Grasse was sailing for the West Indies with a fleet of twenty-six ships of the line, and sometime in July or August he would be available to operate off the coast of North America.

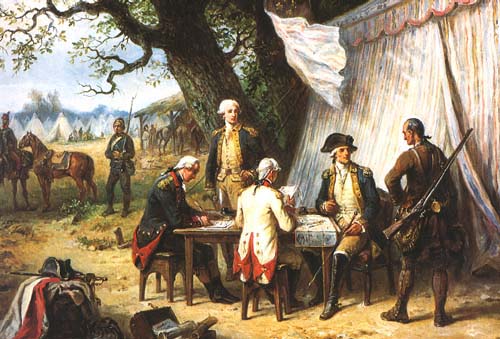

On May 21, the heads of the American and French forces in the United States of America met in Wethersfield at the home of Joseph Webb, which Washington was using as his temporary headquarters. Rochambeau brought Major General Jean Chastellux, with whom Washington had struck up a friendship. Barras had also intended to go, but the appearance of British ships of the line off Newport had convinced him that he had better stay behind.

There were several questions to consider. One was whether the French fleet should remain at Newport or move to Boston, as Versailles instructed. It was decided that the fleet would move. The heavy artillery, too difficult to transport, would be stored at Providence. If the army moved against New York and the fleet was in Boston, Clinton would no longer have the means or motivation to move against Rhode Island, and five hundred militia would suffice to guard Newport.

But the primary question on the table was where the combined American and French armies should go—to the Chesapeake to fight Cornwallis, or to the Hudson River with an eye toward taking New York?

There was no question in Washington’s mind. Like a dog beside the dinner table, for two years he had been camped outside New York, looking longingly and hungrily at the city. He had been chased out of there, badly beaten, five years before, and now he had a chance to take it back. What’s more, with the French transports having sailed, there would be no moving of troops by sea. If the armies were to go to Virginia they would have to march there. In summing up the decisions made at Wethersfield, Washington wrote,

The great waste of Men (which we have found from experience) in the long Marches to the Southern States; the advanced season now, to commence these in, and the difficulties and expense of Land transportation thither. . . point out the preference which an operation against New York seems to have, in present circumstances, to attempt sending a force to the Southward.

Rochambeau offered the possibility that a large French fleet might arrive off the American coast and asked how that might change the equation. Rochambeau, of course, knew about de Grasse’s sailing with twenty-six of the line, but for the sake of secrecy he had been forbidden to share that information, even with Washington. Washington, however, was fully aware of de Grasse’s sailing and the size of his fleet, Chastellux having leaked the information to him. Now he and Rochambeau spoke in hypotheticals, neither able to admit what both knew.

But the possibility of French naval superiority did not change Washington’s mind. If a French fleet arrived off the coast, he felt they should go to New York, though he would agree that they might be “directed against the enemy in some other quarter as circumstances shall dictate.”

Rochambeau’s mind was not changed either. He still preferred the Chesapeake. But Washington called the shots, and one of Rochambeau’s finest qualities was that he never forgot that. New York it would be. Unless he could help it.