4 members of Operation Tombola (3 are identified as Harvey, Manners and Charles McConnell [centre].)

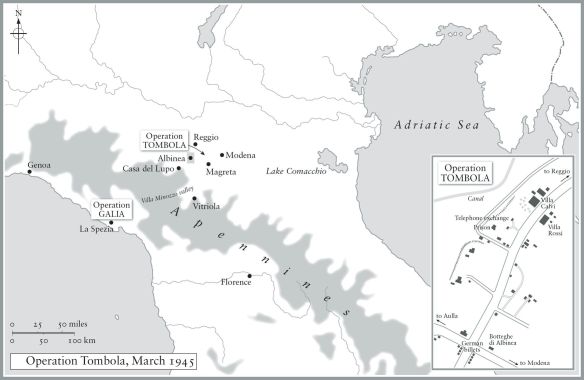

On the afternoon of March 26, 1945, two young Italian women cycled into the little village of Albinea, south of Reggio. Usually a drowsy backwater, Albinea that day was a scene of considerable bustle. The German LI Corps had set up its headquarters in the town, some twenty miles north of the last line of German retreat running along the ridge of the Apennines. German officers had commandeered and taken up residence in Albinea’s two largest buildings: the grander Villa Rossi, on the east side of the main road, was the headquarters of the corps commander, while Villa Calvi, on the opposite side of the road, surrounded by trees, housed the German chief of staff and bureaucracy. Four sentries were posted outside each of the villas, checking the papers of everyone who entered. Six machine-gun posts had been erected behind sandbag ramparts around the village, and an eight-strong German patrol marched up and down the main street. The LI Corps had dug in for a long stay.

The two women, dressed in Italian peasant clothes, attracted no attention whatever. After half an hour spent discreetly observing the activity surrounding the divisional headquarters and flirting with the sentries, they headed back down the road in the direction they had come.

An hour later they reached Casa del Lupo, a farm set back from the road with a large shed that usually housed oxen and now contained one of the oddest units ever assembled under SAS command: twenty British soldiers, forty Italian partisans, and some sixty Russians, deserters from the German army and escaped prisoners of war led by a swashbuckling Russian lieutenant. Their number also included a Scottish bagpiper, dressed in a kilt.

This bizarre little ragtag army was led by Major Roy Farran, still fighting under the nom de guerre Paddy McGinty.

Through an interpreter, the two women partisans reported on the disposition of German forces in Albinea. The town contained some five hundred troops, they reckoned, most of them housed in barracks to the south of the two villas. Farran issued his orders: the force would slip into the town after dark and attack at 2:00 a.m. It was a typically bold plan; but it had also been explicitly vetoed by the 15th Army Group, led by the American general Mark Clark, under whose command Farran was supposedly operating. No matter—Farran’s orders were to spread alarm among the German forces by giving the impression that large numbers of British paratroopers were operating behind the lines. Blowing a German corps headquarters to pieces in the middle of the night with his “motley band of ruffians” seemed to him a good place to start.

Over the previous months, the SAS had been widely scattered through Europe. Two 1SAS squadrons had spent Christmas in Britain, where Paddy Mayne was planning the next stage of operations in northern Europe. The French 4SAS was deployed to the Ardennes, along with the Belgian SAS, and a squadron of 1SAS, to bolster defenses against the counteroffensive launched by the Germans on December 16, 1944.

Much to his satisfaction, Bob Melot, intelligence officer and desert veteran, had found himself stationed in Brussels, the city of his birth forty-nine years earlier. He moved in with his mother. Melot had cheated death in Libya, Italy, and occupied France; he had proved his hardiness so often, and survived so many wounds, that he had come to seem immortal and, to the younger recruits, almost impossibly old. On November 1, he was driving his jeep to a party in the suburbs of Brussels when he skidded off the road and into a ditch, striking his head on the bulletproof windscreen. By the time rescuers reached the wrecked car, Melot had bled to death. He was buried in the Brussels town cemetery, his coffin carried by six SAS soldiers. Melot had become a beloved mascot for the brigade, though the gently ironic, Arabic-speaking Belgian seemed an unlikely recruit for a ruthless British special forces unit. But then courage, like death, seldom appears where it is expected.

Operations behind the lines in northern Italy were proving particularly demanding, due to the mountainous terrain and the fickle qualities of the local partisans. Six months before Farran crept up to Albinea, a team of thirty-two men from 2SAS had parachuted into the countryside north of La Spezia on Operation Galia, with orders to attack supply routes behind the shifting front line. The team was led by Captain Bob Walker-Brown, the son of a Scottish surgeon who had joined the SAS after successfully tunneling out of an Italian POW camp, crawling to liberty through the main sewer, and then walking to the Allied lines. He had an enormous mustache, a bluff sense of humor, an upper-class accent so fruity that the men barely understood his commands, and a habit of saying “what, what” after every sentence, thus earning himself the nickname “Captain What What.” His principal task was to deceive the Germans into thinking that an entire parachute regiment had landed, and thus divert German forces from opposing the offensive by the US Fifth Army. His orders were to make “the presence of the SAS known to the enemy in the quickest possible time.” This Walker-Brown did by attacking anything and everything between Genoa and La Spezia: he ambushed convoys on the Genoa road, mortared villages occupied by German and Italian fascist troops, shot up marching columns, and, in one particularly spectacular coup, attacked a staff car, which was afterward found to contain “a high fascist official,” now dead, and about 125 million lire in a suitcase.

The Germans, now in no doubt whatever about the SAS presence among them, launched an intensive manhunt, believing, according to a German prisoner, that they were under attack from a force of at least four hundred parachutists. “Suitably flattered” by this tenfold inflation of his team, Walker-Brown was hiding out in a deserted village when he received word from the partisans that “a large force of Germans [had been] observed at 250 yards advancing in extended order.” He decided to beat a retreat across some of the highest and coldest mountains in Europe.

Most of the unit’s equipment had been either lost or stolen by the partisans, including rations, rucksacks, and sleeping bags. The radio was broken. The mule drivers had run away, along with their mules. The mountain tracks across Monte Gottero were “sheets of solid ice,” wrote Walker-Brown. “Weather conditions were very severe. It was cold and there was heavy snow on the ground [that] made movement extremely difficult and tedious.” After twenty-four hours of wading through snow at times waist deep, they crossed the summit, only to discover that a combined force of German ski troops and Mongolian soldiers were in close pursuit and barely an hour behind them. The large band of partisans holding Monte Gottero “immediately vanished into the mountains on hearing this intelligence.” Walker-Brown paused briefly in the mountain village of Boschetto before pressing on. “By this time we had completed 59 hours continuous marching without rations or rest.” An hour after the SAS had left Boschetto, the village was attacked by a force of two thousand Germans, its partisan defenders captured and then killed. The pursuers finally abandoned the chase, and Walker-Brown’s weary force could get some respite, but by early February 1945 he judged that his men were too ill and exhausted to continue, and headed toward the front line. “Owing to the physical condition of the men it was not possible for them to carry much on the last stage of the march.” Determined to “reach the Allied lines at all costs” and with only a single tin of bully beef left to eat, Walker-Brown led his men across the heights of 5,500-foot Monte Altissimo, waded the river Magra, and finally reached an American forward patrol. He was awarded the DSO for his “display of guerrilla skill and personal courage,” but he deserved another medal for understatement above the call of duty: the trek, he said, had been “difficult and tiring [what, what].” Just six of Walker-Brown’s team had been captured, but he estimated they had killed between 100 and 150 Germans, destroyed at least twenty-three vehicles, and kept hundreds of enemy soldiers scouring the mountains when they might have been fighting the Americans.

That operation was a foretaste of what Roy Farran was planning in Operation Tombola, the grand and savage finale to the SAS campaign in Italy.

“The details of this operation might well be from a book by Forester,” wrote Farran, a reference to C. S. Forester, the creator of the popular Hornblower adventure novels. On March 6, 1945, an advance party of parachutists had landed safely south of Reggio, to be greeted by Italian partisans. Farran had been instructed by 15th Army Group headquarters that he should remain in Florence to coordinate operations; he could fly with the men to the drop zone and act as a dispatcher, but should on no account parachute in himself. He later claimed that he had “fallen out of the aeroplane by mistake.” It would take more than a mere order to prevent Farran from leading his troops into battle.

Once on the ground, he set about fashioning a guerrilla unit out of some exceptionally unpromising ingredients: “140-odd Italians of mixed political affinities,” about 100 Russians and only 40 trained SAS men. There were also some 15 women partisans, used as couriers (“staffettas”) and intelligence gatherers. Farran’s new force was clad in a bewildering variety of uniforms—Italian, American, British, and, confusingly, German—worn along with bushy beards, bandanas, and nonmilitary hats. “Many had only one eye,” Farran noted, several lacked shoes, and all were “armed to the teeth with knives, pistols, tommy guns and rifles.”

“I was very shaken indeed by the appearance of the raw material,” wrote Farran after reviewing the troops under his command. They resembled, he decided, “a picture of Wat Tyler’s rebellion.”

Their military caliber was as varied as their dress. Some of the Italian partisans were veteran mountain fighters, but “the rest were absolutely useless.” A fierce enmity smoldered between the Italian communist partisans, the Christian Democrat “Green Flames” led by a handsome young priest named Don Carlo, and a newly formed right-wing group commanded by a piratical and corrupt former quartermaster, known only as “Barba Nera” (or Black Beard). The Russians were brave and enthusiastic, but unpredictable. The leader was Victor Pirogov, a former Red Army lieutenant who had escaped from a German POW camp and fought under the more Italianate name Victor Modena. “A big, blond Russian from Smolensk, with a charming smile and a great reputation as a partisan,” he cut an extraordinary figure, clad in blue peaked sailor’s cap and German jackboots, with a strip of blue parachute silk wound around his neck.

An initial series of raids, launched from Farran’s mountain base, did little to reassure him that his recruits were up to the job: the Russians showed a “marked reduction in their offensive spirit after they had taken a few casualties,” and without the SAS to prod them forward “the Italians were only just worth feeding.” Still, with a mixture of “threats and persuasion,” and resupplied by airdrops of food and ammunition, Farran was convinced he could instill some sort of military discipline into this “heterogeneous force.” They took the name Battaglione Alleata (Allied Battalion) or, less formally, Battaglione McGinty.

Knowing that uniforms, however approximate, promote cohesion, Farran sent a message back to base requesting a consignment of berets, along with green and yellow feather hackles. The force also adopted woven badges with the SAS motto in Italian: “Chi osa vince.” The women staffettas had “McGinty” embroidered on their pockets and a badge consisting of a bow and arrow. In a final flourish, “to add character to this already colourful and composite force” (as if it needed any more), Farran summoned from headquarters a bagpiper from the Highland Light Infantry, David Kirkpatrick, who made his first parachute descent to join this strange crew. “Whether he jumped in a kilt has not been recorded,” wrote Farran, who later admitted that he had wanted Scottish musical accompaniment to the operation in order “to stir the romantic Italian mind and to gratify my own vanity.” A somewhat more practical 75mm howitzer was dropped at the same time.

The battalion had been in training for two weeks when Michael Lees, the SOE officer liaising with the local partisans, planted a plan in Farran’s mind. The German LI Corps had established its headquarters just twenty miles away at Albinea: a tempting though difficult target. “I had long toyed with the idea of a really large operation behind the centre of the front [and visualized] myself…at the head of a whole army of partisans.” The top brass in Florence, however, had other ideas. After initially approving the attack on Albinea, and dropping a useful batch of air-reconnaissance photographs, 15th Army Group HQ received intelligence reports that the Germans were planning their own assault on partisan groups and unequivocally ordered Farran not to proceed. Once again Farran ignored the command, and later wrote, with ringing insincerity: “Unfortunately I had already left on the long march to the plains when the cancellation was received on my wireless set in the mountains. In any case, having once committed a partisan force to such an attack, any alteration in the plan would have been disastrous to guerrilla morale.”

By the morning of March 26, the hundred-man-strong raiding party was safely installed in an ox shed at Casa del Lupo, ten miles from Albinea. Farran dispatched two of the Italian staffettas, Valda and Noris, to reconnoiter the target. “An attractive girl could pedal through a German-held village with impunity” and gather vital intelligence, reflected Farran. “How a woman can loosen a soldier’s tongue.” Noris was a particularly arresting figure, “a tall, raven-haired girl with Irish blue eyes, as brave and dangerous as a tigress and completely devoted to the British company.” In camp, she wore a red beret, a battledress blouse, and a skirt sewn out of an army blanket with a pistol tucked into the waistband. Farran was not scared by much, but he was a little afraid of Noris, and more than slightly smitten. “Noris was worth ten male partisans.” She and her companion returned after five hours and reported: “Everything seemed normal in Albinea.”

The raiding party emerged in small groups from the ox shed in the misty, predawn darkness of March 27 and headed for the town. Once in Albinea, the Russians formed a cordon across the road, “to cut off the objective from help.” Several hundred Germans were asleep in billets about four hundred yards to the south. These would surely come pouring up the road as soon as the shooting started, and Victor Modena and his men would be waiting. The two assault teams, each composed of ten SAS men and twenty Italian partisans, crept toward the two villas: Farran and the remaining force would provide covering fire, and send up a flare after twenty minutes to signal the order to withdraw.

A few minutes after 2:00 a.m., an explosion of gunfire mixed with the eerie wail of bagpipes, as the piper added his own, surreal element to the assault with a loud rendition of “Highland Laddie.” The sentries guarding the villas died “before they knew they were being attacked.” The front door stood open at the Villa Rossi, where the general commanding the LI Corps, a divisional commander, and thirty-seven other officers and men had been peacefully sleeping a few moments earlier. The raiders stormed in, firing wildly and hurling grenades. A siren on the roof sounded the alarm, every light in the house seemed to blaze on at once, and the occupants, lurched from sleep, seized their weapons and responded with the desperate speed of cornered men. A frantic battle took place in the hallway, bullets screaming off the marble walls. “After fierce fighting the ground floor was taken but the Germans resisted furiously from the upper floors, firing and throwing grenades down the spiral staircase.” An attempt to charge up the stairs was repulsed; a second attack was also beaten back, leaving two SAS men dead, one officer and an NCO. The surviving Germans then tried to fight their way out: six were gunned down on the stairs. Two surrendered. The Italian partisans “dealt” with them—Farran’s code for summary execution. After twenty minutes, the attackers withdrew, leaving a fire burning in the ground-floor kitchen.

At the Villa Calvi, on the other side of the road, another vicious battle was still raging. Finding the door locked, the raiders used a bazooka and Bren gun to blow off the lock, then rammed open the door, tossed in a handful of grenades, and crashed inside. The delay had given the defenders more time to prepare, and another brutal close-quarters battle took place. “The din was deafening,” said one of the SAS participants. After several minutes of “furious fighting,” the Germans again withdrew up a spiral staircase to the upper floor leaving behind eight dead, including the chief of staff himself, Colonel Lemelsen. From the lawn, the raiders poured a torrent of Bren-gun and bazooka fire into the upper floors. Wooden furniture, files, and curtains were dragged into piles in the registry and map rooms downstairs, and then ignited with plastic explosive and a bottle of petrol. Farran was in his element: “Bullets were flying everywhere, and over it all, the defiant skirl of the pipes.” As the raiders withdrew, the building was “burning furiously.”

As expected, German troops had swiftly emerged from their barracks and rushed north in an attempt to relieve the besieged occupants of the villas, only to meet Victor Modena and his men spread out across the road. “The Russians returned fire very accurately and their ring was never broken during the attack,” wrote Farran with somewhat surprised approval.

On Farran’s signal, the raiders first headed west, then south, taking a wide circle back to the rendezvous at Casa del Lupo with dawn beginning to break. As the force pulled out, Villa Calvi exploded. “The sky was red from the blazing villas,” wrote Farran.

Carrying their wounded on stretchers, fueled by Benzedrine tablets, pummeled by driving rain, the party made its way across country “buzzing with Germans” and back into the hills. They reached the base camp in the Villa Minozzo valley twenty-two and a half hours later, by which time Farran’s old leg wounds had rendered him unable to walk, and he was brought in, much to his embarrassment, on the back of a pony. The partisans, “cheering over and over again for McGinty and Battaglione Alleata,” immediately threw a party: “Fried eggs, bread and vino by the gallon.” With the piper playing, the SAS men gave the partisans a demonstration of the eightsome reel, a traditional Scottish dance, a spectacle that Farran described as “one of the greatest moments” of the campaign.

Farran calculated that at least sixty Germans had been killed in the attack on Albinea. The LI Corps command center had been utterly destroyed, along with “the greater part of the headquarters’ papers, files and maps.” Villa Calvi had been demolished, and Villa Rossi damaged beyond repair. A joint force of British parachutists and partisans had successfully penetrated and then devastated a German base far behind the lines that had seemed, to its occupants, so heavily guarded and so far from the battlefield as to be invulnerable. The crushing effect of the raid on German morale was doubtless reinforced by the death of Lemelsen, a relative of the overall commander of the German Fourteenth Army in Italy. Gratifying reports reached the SAS camp of the raid’s impact on the German troops. “The Germans in the whole area are now in a state of alarm.”

For his troubles, Farran narrowly escaped a court-martial. He was given a “rocket” by 15th Army Group headquarters for launching a “premature attack disregarding orders,” which he cheerfully disregarded.

Throughout the spring, as the 15th Army Group offensive got under way, Farran’s mobile “guerrilla battalion,” now reinforced by the arrival of several jeeps, fought a series of actions against the retreating Germans. Farran left a memorable description of his men preparing to go into action from their base in the little village of Vitriola.

Long, greasy-haired pirates were sitting on the steps, cleaning their weapons in the streets. Jeeps dashed about everywhere with supplies. The night air was broken by the tap-tap-tap of Morse from our wireless sets and the Russians sang as they refilled their magazines. At night one could hear Modena’s tame accordionist and occasionally Kirkpatrick’s pipes, which were now suffering from lack of treacle, an essential lubricant for the bag, I am told.

On April 22, he learned that an extended column of German lorries, carts, and tanks was slowly crossing the ford at Magreta, an ideal ambush site. The raiders hid in the foothills, and then opened fire at 2:30 in the afternoon: trucks exploded, horses stampeded, the convoy ground to an appalled halt, sitting ducks in the water. “The shooting was very good,” wrote Farran grimly. “It was obvious the Germans were really on the run.”

Farran’s picaresque little army had inflicted damage out of all proportion to its size and his own expectations: at least three hundred Germans killed and fifteen trucks destroyed. “There is little doubt that the actions considerably accelerated the panic and rout of some three or four German divisions,” wrote Farran. As in North Africa and France, the essential value of the operation lay in tying up enemy troops, fomenting fear and uncertainty, and the demoralizing “effect of the presence of so formidable and enterprising a force in the immediate rear of the enemy.”

On May 2, Field Marshal Alexander sent out a “Special Order of the Day” to Allied forces in the Mediterranean theater:

After nearly two years of hard and continuous fighting which started in Sicily in the summer of 1943, you stand today as victors of the Italian campaign. You have won a victory which has ended in the complete and utter rout of the German armed forces in the Mediterranean. By clearing Italy of the last Nazi aggressor, you have liberated a country of over 40,000,000 people. Today the remnants of a once proud army have laid down their arms to you—close to a million men with all their arms, equipment and impedimenta.

The second phase of war for the SAS, which had started almost two years earlier at the other end of Italy with the assault on Capo Murro di Porco, was over.

A month before Farran’s attack on Albinea, Brigadier Mike Calvert became commander of the SAS Brigade. Calvert had fought with the British special forces known as the Chindits during the Burma campaign, and had seen ferocious action behind the lines. On his appointment “Mad Mike” Calvert sent a message to the men now under his command: “You are special troops and I expect you to do special things in this last heave against the Hun.”