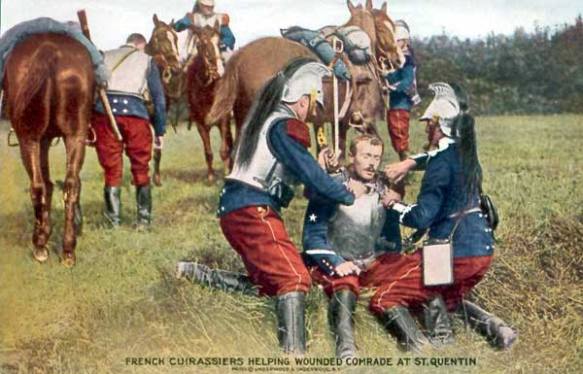

By the end of the nineteenth century cavalry operations in European armies had become a matter of some doctrinal uncertainty. More powerful weapons, firing more accurately and at longer ranges, raised the question of the suitability, indeed the survivability, of the cavalry. This was no less the case in Germany than elsewhere. While the Franco-Prussian War had seemed to show that cavalry could still win a battle by means of the massed charge with cold steel, the true value of the German cavalry during that conflict had demonstrated itself in armed reconnaissance with a view to finding and fixing the enemy; screening and securing German forces; interdicting the enemy’s communications; and, at war’s end, foraging and anti-partisan operations. None of these missions, particularly neither of the first two, had changed by 1900, though some soon would as a result of the widespread application of internal-combustion technology.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, cavalry still possessed the unique ability to move almost at will, though not always rapidly, over the most varied terrain and in nearly all types of weather. Cavalrymen could leave the largely road- and rail-bound infantry literally in the dust. In Western Europe, however, mounted forces faced an interesting potential problem, one that had been noted as early as the late 1860s, namely the congested physical nature of the landscape over which armies might move in future. That portion of the North European Plain stretching from Normandy through France, Belgium, and the Netherlands and into northwestern Germany had a very high population-density by the last quarter of the nineteenth century. With it came a significant degree of industrial urbanization and attendant infrastructure. This infrastructure constituted a set of major obstacles to the free movement of mounted troops: intensively cultivated, and therefore very soft and wet, footing; numerous canals and railway lines; mine-pits and slag heaps; and innumerable fences and garden walls, the latter a delight to fox hunters but a real hindrance for heavily laden cavalrymen and their horses. Making these obstacles even more troublesome were the increasingly vast and complex fortifications strewn right across northwestern Europe from Liège and Namur past Luxemburg to Verdun. It was the latter’s job specifically to complicate the movement of armies and thereby hinder invasions or block them altogether.

As the Franco-Prussian War had so amply demonstrated, modern war had become terribly consumptive not only of cavalrymen but also of horseflesh. Despite advances in breeding and veterinary services, loss rates rose still further as the twentieth century dawned. Nevertheless, German and other cavalrymen assumed that horsed regiments would continue to have their place in the order of battle, even in the congested regions of northwestern Europe. The Germans’ experience in 1870–1871 had done little to convince them otherwise. On the contrary, German observers felt that the cavalry should be strengthened and modernized, not reduced or—worse—eliminated. For example, one of Germany’s most noted military authors of the era, General Friedrich von Bernhardi, called the early-twentieth-century strength of the German cavalry lamentably weak when compared to the mounted forces of France or Great Britain. The Boer War, he wrote, had shown what highly mobile and hard-hitting cavalry columns could still do, even in an age of high-powered infantry weapons. The key, he insisted, lay in ensuring that the German cavalry possessed its own accompanying bicycle-mounted infantry and more effective artillery, as well as training cavalrymen better as marksmen. Such additions would ensure that the horsemen could, if necessary, operate independently and with sufficient firepower to cause the enemy real damage. All the while they would retain their vaunted mobility, even though he never really explained what bicyclists would do once they ran out of road. He also cautioned, however, that every new war would create new conditions and totally unforeseen circumstances to which the cavalry, as all arms, would have to be ready to adapt.

Across the English Channel, Sir John French, who had “established his military reputation by his performance as a cavalryman in the Boer War” and who would later become the first commander of the British Expeditionary Force in France, shared this view. Though speaking for the British, his comments were ones that would have been widely shared in Germany. French wrote that cavalry circa 1900 were being taught to shirk exposure on the battlefield as a result of what he considered undue respect for infantry fire. “We ought,” he wrote to the contrary, “to be on our guard against false teachings of this nature…[and the] consequences of placing the weapon above the man” and, implicitly, above the horse. Of course, his own experiences in the Boer War might have taught him otherwise. Between 1899 and 1902, the British cavalry in South Africa “lost 347,000 of the 518,000 [horses] that took part, though the country abounded in good grazing” and possessed a “benign climate.” Of those lost, “no more than two per cent were lost in battle. The rest died of overwork, disease, or malnutrition, at a rate of 336 for each day of the campaign.”

In the absence of motorized vehicles, however, horses remained critical for mobility in that conflict. This fact represented the only real hope for the cavalry’s survival in European armies. Reinforcing the mobile importance of horse-mounted and horse-drawn forces, another feature of the Boer War stood out: among the Trek Boers, “every man was a mounted shot.” Like their earlier American counterparts in the Civil War and in the wars with the Plains Indians from 1850 to 1890, Boer horsemen were the quintessential mounted infantry. Though some of them might yet be armed with sabers, their primary weapon remained the rifle, and the horse served principally as a means of effective crosscountry transport. If there were to be a place for mounted formations at the dawn of the twentieth century, would it not have to be that of mounted infantry who would nevertheless fight dismounted? British cavalrymen increasingly thought so after 1902. Accordingly they were equipped and trained with rifles rather than carbines and achieved a level of firepower and accuracy approaching that of the British infantry. They were becoming essentially what in British and British imperial terminology were designated mounted rifles: skilled “horsemen trained to fight on foot, men who are mounted and intend to perform all the duties of cavalry, except that which may best be described as ‘the shock.’ It is expected of them that they should perform all the outpost [sic], reconnoitering, and patrolling of an army in a manner similar to cavalry; the only difference being that they must rely solely upon their fire power for defensive and offensive action.”

Commenting on the lessons to be drawn from another war of the period, the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, German and Austrian officers came to a rather different set of conclusions. Under the pseudonym “Asiaticus,” a German officer wrote that Russian cavalrymen were too ready to go to ground with their firearms. In doing so, he said, they repeatedly sacrificed the cavalry’s greatest asset, namely its mobility. Similarly, Austrian count Gustav Wrangel observed that the Russian horsemen’s experience demonstrated that troopers could not serve both firearms and the saber equally well and be skilled riders at the same time. In any case, Wrangel noted, too great a reliance on firearms robbed the cavalryman of his desire to charge the enemy and implicitly deprived him of his real weapons, the sword and the lance.

Such arguments continued unabated, even as rapid technological change continued to force the cavalry to adapt. Combining horse-soldiers with the technology that did exist culminated in the following calculation: railways would be used for initial operational deployment, as they had been for German armies ever since 1866. Increasingly heavy artillery would be the primary offensive preparation against field positions. The latter would then be taken by infantry assault. For its part, the cavalry would still be used for reconnaissance, screening, security, encirclement, and pursuit, if no longer for the battle-winning charge with swords drawn. One may argue, however, there’s not much terribly novel in this approach. Cavalry had often been used for precisely these tasks in the Western military tradition ever since Hannibal’s charging horsemen cut off the legions’ retreat at Cannae and rode down the survivors (a favor the Romans returned at Zama). The mounted warrior’s ethos and the tradition of the cavalry’s shock value nevertheless lingered up to the outbreak of war in 1914. Even then, however, missions such as long-range screening and reconnaissance or interdiction of the enemy’s lines of supply had not fully displaced the assumption that at least some future battles might still be decided by the massed cavalry attack. In a view no doubt shared among more than a few German cavalrymen, the British Army’s Cavalry Training Manual of 1907 still pronounced as a matter of principle that rifle fire, however effective it might be, “cannot replace the effect produced by the speed of the horse, the magnetism of the charge, and the terror of cold steel.”

One prominent British officer, Colonel G. F. R. Henderson, deduced from the campaigns of the Boer War that the sentiment as expressed in the Cavalry Manual meant that the cavalry at the turn of the century was “as obsolete as the crusaders.” If, however, the matter of the infantry’s use of the bayonet is considered, then the cavalry’s retention of the sword, and even the lance, may not seem so far-fetched, whether in Germany or Great Britain. The same officer had earlier been pleased that the British Infantry Regulations of 1880 had reiterated the psychological and tactical importance of the bayonet at close quarters, despite the by-then-widespread use of smokeless powder, magazine-fed rifles, and rapid-firing field artillery. Admittedly, Henderson modified his opinion about the bayonet’s efficacy as a result of the Boer War, just as he did for the sword-armed cavalry. As the events of 1914–1918 repeatedly showed, however, German, British, and other infantry routinely went over the top with bayonets fixed long after the cavalry on the Western Front was deemed utterly useless. Indeed, the success of the Japanese infantry in their costly assaults against prepared Russian positions at Mukden and Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War seemed to show that the foot soldier’s cold steel could still be employed with decisive effect provided that the attacking infantry had sufficient preparatory artillery support and a sufficient reserve of raw courage while covering the fire-swept zone between the opposing trench lines. Bernhardi, as well as another influential German military writer of the period, Colonel Wilhelm Balck, shared this assessment. Both stressed the “moral factor” (i.e., morale) as much as they stressed the material factor as a determinant of victory. They also applied it equally to the individual soldier and the nation in whose army he served. If, therefore, prominent military thinkers still posited a useful role for the bayonet, and if cold steel really could still frighten an enemy soldier—he need only imagine a foot or more of it being plunged into his gut—then the cavalry’s retention of edged weapons and even lances does not seem so odd.